Let’s face it: the supermarket has dominated our lives lately. It’s one of the few places we can go without too many restrictions. We might even call it “the grocery store,” though many today sell everything from clothing to sporting goods: a giant Walmart does, itself a super-sized version of the General Stores of the early 20th Century. Yet when we think of “groceries,” we think of food and household items.

Let’s face it: the supermarket has dominated our lives lately. It’s one of the few places we can go without too many restrictions. We might even call it “the grocery store,” though many today sell everything from clothing to sporting goods: a giant Walmart does, itself a super-sized version of the General Stores of the early 20th Century. Yet when we think of “groceries,” we think of food and household items.

These stores, in the States at least, go back to Giant Open Air and similar in the 60s. My father was stunned that you could buy tires or a steak under the same roof. At our local Giant Open Air, you could even pick out a steak and have it cooked for you while you watched. Now, restaurants are common in big stores. Wegmans here has a Pub, a Coffee Shop, and a Cafeteria.

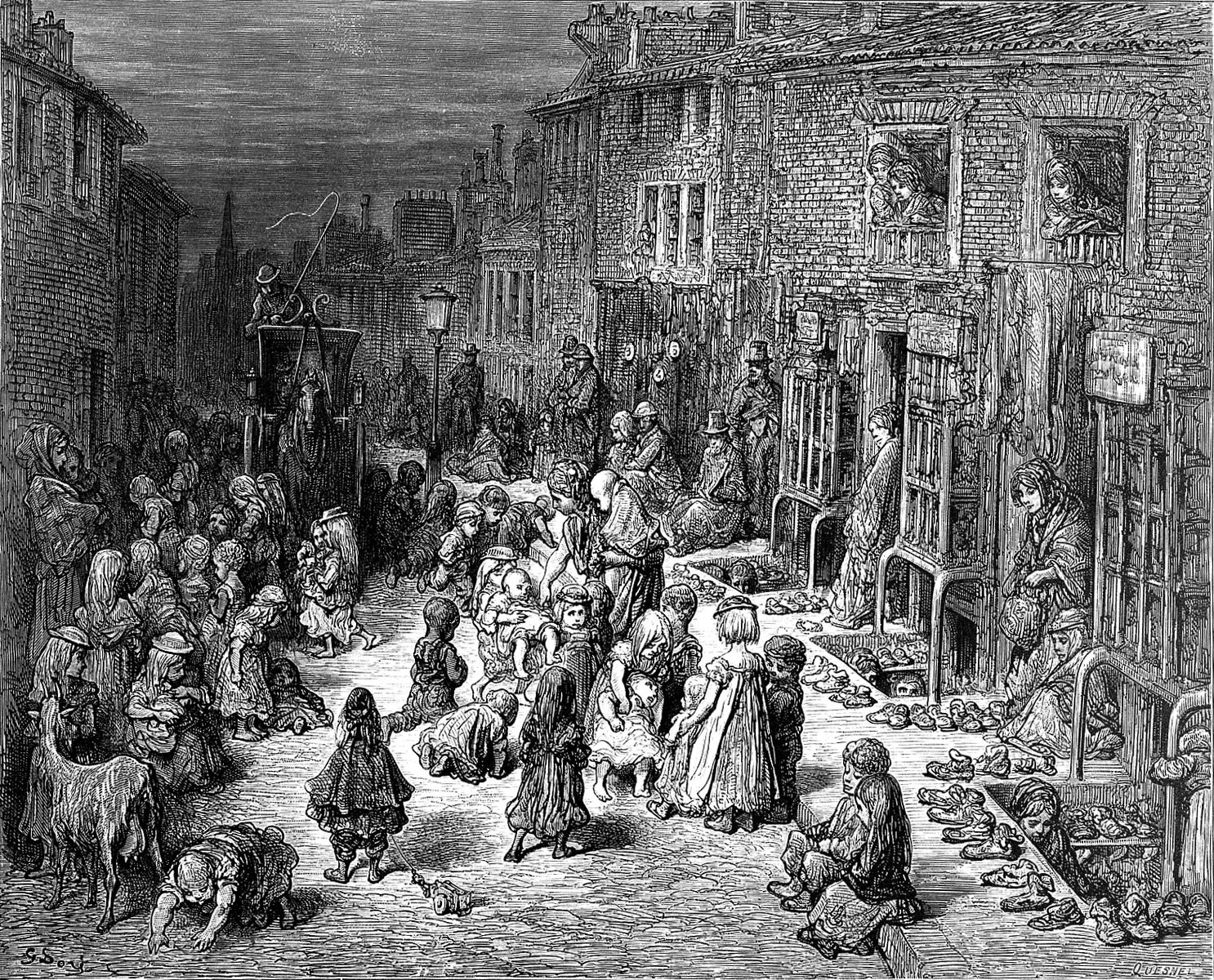

Only in the UK, when I encountered the “Greengrocer,” a produce-seller nearly (and sadly) extinct thanks to the giant supermarkets there, too, did I begin to question what a “grocery” was and where it came from. More recently, an article in The Atlantic about the pandemic and its long-term effects on the grocery industry got me interested in this word.

Picking “grocery” apart when saying it comes up with “gross,” and not in the sickening sense, but the sense of something sold in bulk. We trace the word back to Latin grossus, through Medieval Latin and French to get “grocer,” the merchant who sells things in bulk. Our word goes back at least to the 14th Century, as the OED outlines it.

Before the modern era of packaged goods, that is what folk did: pounds of this, dozens of that. How “gross” also came to mean “disgusting” should be the subject of a future post.

May I admit a certain obsession with grocery stores? Why do I spend time wandering about not only stores, but Groceteria, a site about their history?

My father was a produce wholesaler, after years of driving a produce truck, so I spent hours in various stores, a delight to a kid hoping for a candy bar. In my teens I bagged groceries for the old Food Fair / Pantry Pride chain. It’s nigh impossible to find images of these quotidian, largely forgettable stores. The best I could do is this shot, with “gross” quantities of food on view, from the Food Fair in the now demolished Azalea Mall of north Richmond. That’s a lot of country ham.

The caption here: In October 1966, the television game show “Supermarket Sweep” visited the Azalea Mall Food Fair for a taping. Before an audience of 300, contestants attempted to guess the correct prices of grocery items in order to win minutes of shopping for free merchandise. Bill Malone, behind the register, was the host of the show.

The caption here: In October 1966, the television game show “Supermarket Sweep” visited the Azalea Mall Food Fair for a taping. Before an audience of 300, contestants attempted to guess the correct prices of grocery items in order to win minutes of shopping for free merchandise. Bill Malone, behind the register, was the host of the show.

These were formative experiences, in an era when a cashier could earn a living wage and even retire from a chain store. I always make a point to visit grocery stores in other nations, at least to get things for a picnic. I have learned more about a culture from its grocery stores than nearly anywhere else.

I do wonder how grocery-shopping will evolve in coming years. Will “groceries” come to refer to those things we use at home, delivered to us? Or will we need an adjective for what is perishable, not easily delivered to our doors? Of will grocery-shopping in person wane completely, with modern-day counterparts (perhaps, robots) of the egg, milk, and bread delivery people returning to what was done before supermarkets offered one-stop shopping?

That is for futurists and the Market to consider, not a blog about words. But enjoy your shopping, and may your choices be plentiful and your carts full.

Please send us words and metaphors useful in academic writing by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia; Sainsbury Store. U.K., where I’ve done my share of grocery shopping.

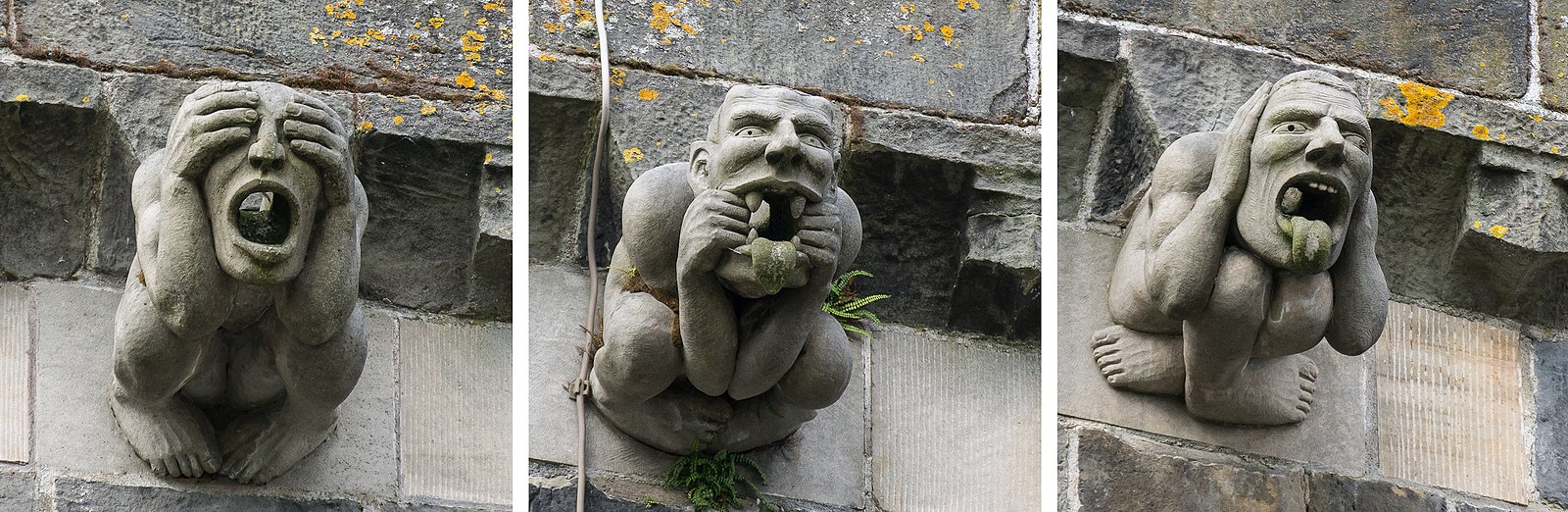

Some time back, I considered the history of the term laconic. Today we meet its antithesis. It’s the stuff of Twitter: running one’s mouth constantly.

Some time back, I considered the history of the term laconic. Today we meet its antithesis. It’s the stuff of Twitter: running one’s mouth constantly.