Wrong I was, completely wrong, when I implied that the COVID-19 outbreak would not become a pandemic. Now we are talking not only about that unfortunate development but also its impacts on the global economy and the US election.

Wrong I was, completely wrong, when I implied that the COVID-19 outbreak would not become a pandemic. Now we are talking not only about that unfortunate development but also its impacts on the global economy and the US election.

No one can predict when a new disease will emerge, so they provide perfect case-studies of black-swan events. Why that avian metaphor? It’s ancient, but the meaning has not changed. As I learned from a surprisingly erudite Wikipedia entry, in the 2nd Century, Roman satirist Juvenal mentioned “a rare bird in the lands and very much like a black swan.”

Today in the New York Times, columnist Farhad Manjoo notes now “I hadn’t properly accounted for what statisticians call tail risk, or the possibility of an unexpected ‘black swan’ event that upends historical expectation.”

Let’s look at the reasoning behind the metaphor. Wikipedia’s editors suggest to qualify it must be “an event that comes as a surprise” when, say, one assumes that all swans are white. That black bird, then, could not be a swan. In consequence, limited imaginative thinking can lead to disaster. That’s because a black-swan event also has large-scale effects.

We may not be talking about birds, but, say, a new way that birds pass infections to humans. Blinded by prior experience, researchers miss the black swan in the lake.

You may have heard the old saw that goes, in some form, “the military is always fighting the last war.” The leadership at Pearl Harbor and the builders of the Maginot Line were thus surprised by military black swans: strong airstrikes from carriers or blitzkrieg warfare featuring highly mobile armored units that bypass fortifications.

Other famous black-swan events include the start of the First World War of 1914, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event of 65 million years ago, the rapid adoption of the Smart Phone after the iPhone debuted in 2007. I’d personally not include the Housing Crisis of 2008. Many of us saw it coming, so it offered few surprises though it did have a large effect, as all black-swan events have.

We may live in a time of black swans. Manjoo’s column claims that we must adapt to increasing chaos. I hope he is wrong about the many black swans coming to roost.

Please send us words and metaphors useful in academic writing by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

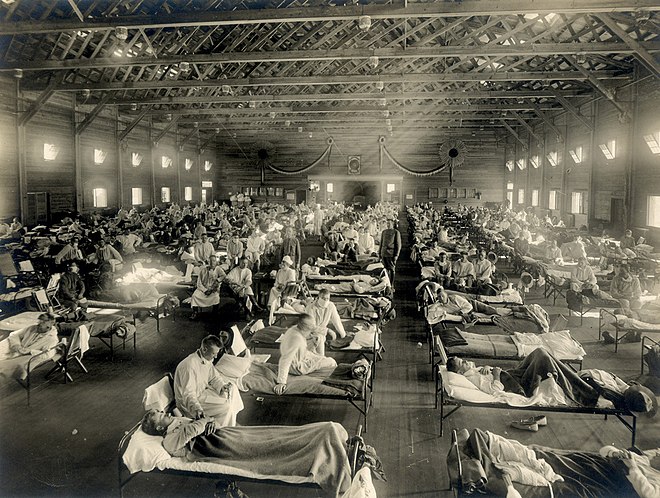

Image courtesy of Wikipedia.