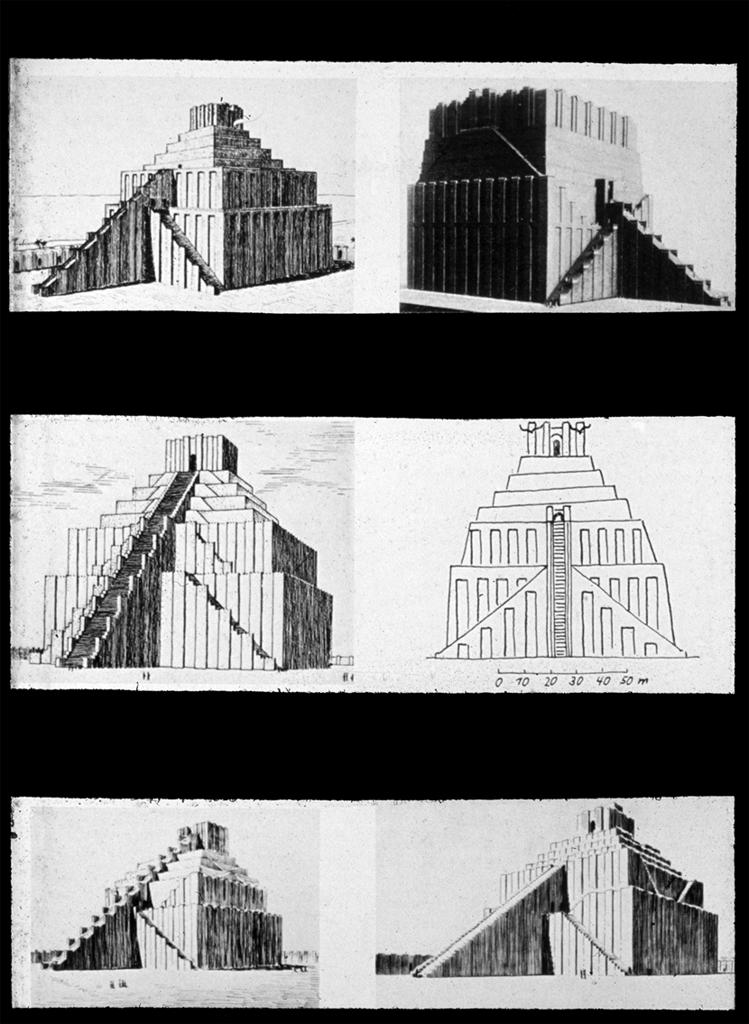

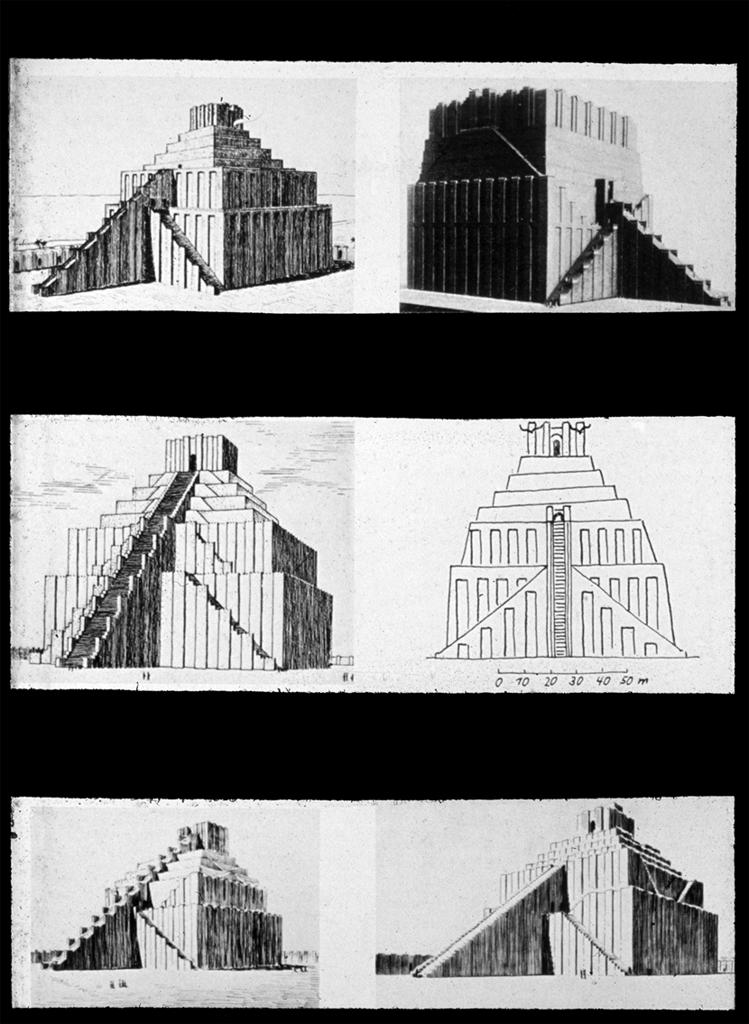

In Genesis 11, the building of the Tower of Babel is represented as the result of human organization facilitated by a single language. The tower itself is an ideal representation of written language: made of many small parts carefully assembled into a structure that encourages further construction and reveals complexity through an increasingly elevated perspective developed over time. In the Biblical story, Jehovah’s fear is that humanity will be able to achieve whatever it imagines and this prompts him to prevent this by creating a confusion of many languages:

Genesis 11:5- 9 “And the LORD came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded. And the LORD said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech. So the LORD scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city. Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the LORD did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the LORD scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.”

And we might think Jehovah was right. After all, look at what we’ve achieved without a single unifying language: from cuneiform to the Cassini-Huygens Mission, humanity has advanced through a shrinking galaxy of about 7000 languages. But it is a single, shared language that is represented in this story as the key to high human achievement and some believe this today.

I used to believe in the deliberate promotion of English as “the” global language until a student essay took issue with my assertion and made a good argument against it. In a nutshell, my student noted that diversity of language is important for maintaining the broadest possible understanding of our world. He argued that if we had a single global language like the 1500-word “Globish” being promoted today, even if other languages were permitted, the dominant language would naturally drown out and eventually replace them. Diversity of linguistic expression may be as important for human knowledge as biological diversity is for promoting maximum health in an ecosystem.

In The Wall Street Journal “Lost in Translation” by Lera Boroditsky reviews the question of linguistic diversity along with recent cognitive research that indicates a profound connection between language and perception. That our language shapes the way we understand the world seems obvious, but this tenet has been resisted and rejected over the years mostly, Boroditsky claims, due to the influence of Chomsky’s “universal grammar” theory which dismisses differences in languages as insignificant. Boroditsky’s article is full of interesting tidbits about linguistic differences such as various conceptions of “space, time and causality” that demonstrate how profoundly language can shape perception. To explore these differences can only expand our understanding, and so it behooves us to resist any homogenizing force that would eliminate or obscure them.

One linguist who challenges Chomsky’s theory is Dan Everett whose work with the Brazilian Piraha is outlined in “The Interpreter” by John Colapinto in The New Yorker. Unlike our number-obsessed culture with its innumerable systems of measurement, the Piraha only have three quantity words: one, two and many. It only takes a moment to imagine the vast cultural differences we would experience with such a counting system.

With a simple and loose “one, two, many” system of counting, we may have never been able to achieve the $35 laptop recently unveiled by the Indian government, but that may actually be a good thing. Such a heresy might need some extensive defense, so before I’m tied to the stake the short version of my concern is this: the $35 laptop could easily be the same kind of homogenizing force that a single global language would, even if it is used with a variety of languages. As much as I love my Mac and spend hours online, using a computer is just one of many ways of knowing and it has its limits.

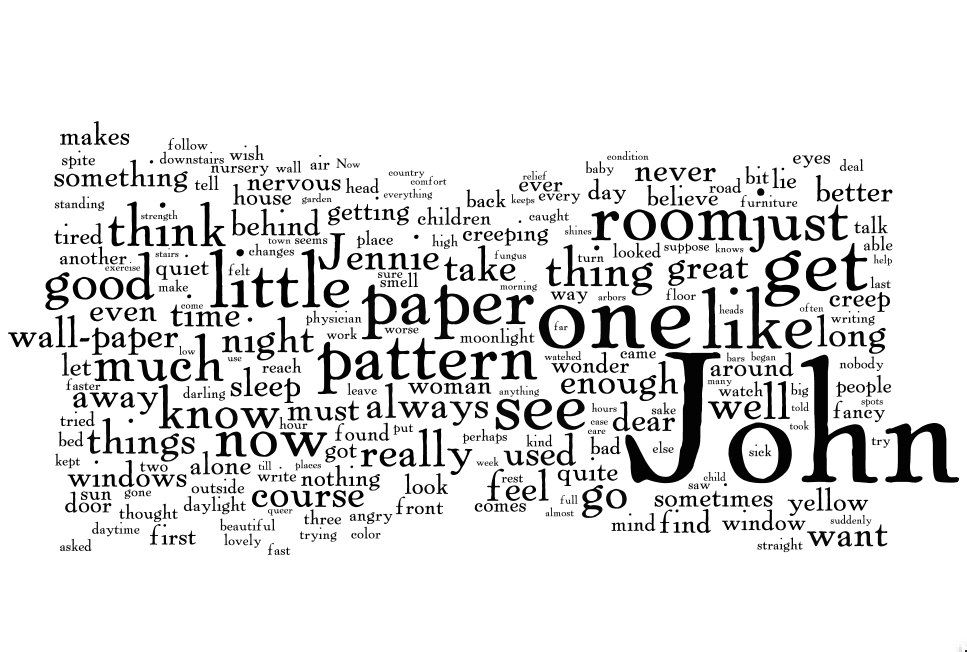

The problems of homogenized thinking and experience are just one of several relevant ideas that Aldous Huxley explores in Brave New World where people are cloned, conditioned to hate reading, repeat simplistic slogans and fear nature and natural experience – sound familiar? We can get a glimpse of his insight into the question in chapter 8 in a scene where John Savage is being taught by old Mitsima, an elder on the reservation: ” ‘First of all,’ said Mitsima, taking a lump of wetted clay between his hands, ‘we make a little moon’…Slowly and unskillfully he imitated the old man’s delicate gestures…to fashion to give form, to feel his fingers gaining in skill and power – this gave him an extraordinary pleasure…they worked all day, and the day was filled with an intense, absorbing happiness.”