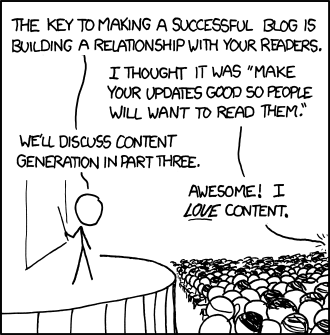

image source: Creative-Commons licensed image from xkcd

My colleagues are, increasingly, reading blogs and assigning them in classes. “Weblogs,” the full name for this medium, appear in every class I teach. I use them for weekly reading responses, warm-ups for formal writing, and even for graded multimedia projects impossible on paper.

A blog like this, rather than a closed discussion list at a course-management system like Blackboard, provides students with several real-life advantages. First, the secondary audience for a blog, one far greater than professor and classmates, enables writing for publication in the real-world Internet, rather than what we techies often call a “walled garden.” Second, blogs resemble the sorts of collaborative tools coming into use in the workplace. Finally, blogs are not bound by the conventions of print, and that enables them to do things impossible on paper.

How to Get Started

In planning the workshop on academic blogging, I decided to first write what journalists call a “nutgraf,” or a few sentences that sum up the focus and claims the writer will make. Here’s mine:

Academic blogging opens a new and easily used venue for student and faculty writers. A blog provides a number of advantages when compared to traditional papers, such as the ability to embed photos and videos, the use of easy-to-manage feedback from other writers in a class, and an informal style that tends to help writers still learning to write for the academy. Blogs also pose certain problems, and in my blog post I will outline them as well.

Now that you have my nutgraf, how about those problems? From my experience with many student bloggers, here are some issues that hurt their assessment when I ask them to blog.

Paper-based thinking: Blogs and other Web-based media do not need double-spacing and they do not tend to support paragraph indents. Instead, single-spacing, left-justification, and one blank line between paragraphs suffice.

Unclear focus: preparing a nutgraf avoids the sort of rambling monologue that can afflict a new blogger. Keep in mind, readers, that your readers choose to visit your site. Keep them informed and stay focused. For this reason, blogs rarely cover more than a single topic.

Broken links: Non-working links hurt all sorts of Web texts, but a blogger should take extra care; one’s reputation depends on providing accurate references to other materials. In print, an analogous mistake might be a severe error in a citation, such as providing the wrong title for a printed work.

To avoid such errors, be certain that every link works when you preview or publish the post. Note that links to on-campus resources requiring a university log-in will not work off campus. Check all links from a computer at home or find a public version of the material.

Clumsy links: Also beware of pulling in URLs (Web addresses) like this:

Instead of testing readers’ patience, if the post needs a URL rather than a link from text (as I have just done) consider a Web site that can make long URLs short. These “crunched” URLs persist, and I have had good luck with bit.ly and tinyurl.com. I used the latter to shorten that monster address above:

http://tinyurl.com/6e4fyez

In some classes, and for formal projects published online, you may not be permitted to do this. Check with your professor and a handbook for documentation. Both MLA and APA formats now give advice on how to shorten a URL for publication.

Microsoft Word & Blogging: Word is designed for printed documents, no matter what appears under its “save as” menu. Word works wonders on paper, partly because the software enables dozens or even hundreds of fonts, sizes, and margin-changes. But Word does this through hidden formatting codes. We never see them when cutting and pasting to a blog, but in some blogging software, these typographic phantoms cause nightmares.

I just typed this line into Word: “Now is the time for all talented geeks to come to the aid of Cyberspace.”

Here is what I got when I copied the text from Word and pasted it to the editor of Google’s Blogspot:

<style>

@font-face {

font-family: “Cambria”;

}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: “Times New Roman”; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

</style>

<div class=”MsoNormal”>

Now is the time for all talented geeks to come to the aid of Cyberspace.</div>

Oh oh. Normally, this is not a problem, if a blogger does not put any bolds, underlines, or other formatting into Word. If those features appear, however, it may take hours to untangle the mess. I have encountered lines that do not want to single-space, strange changes of fonts, and more.

Random eye-candy: Why use a photo, video, or other illustration in a blog? They can emphasize an argument and save you words. In every case, they should be placed close to the material referenced.

When choosing images, search for those licensed for non-commercial reuse. You can do this with the advanced options for Google image search as well as Flickr. I’m sure that most other image-sharing sites have ways to find content with Creative-Commons licensing. The candy-apple image appeared licensed for reuse in a Google search.

Bad Tags: Tagging blogs permits readers to aggregate topics by clicking a tag. Huge sites need this. I’ve found that even my blog on virtual worlds and gaming, “In a Strange Land,” needs tags so I can, say, separate how-to advice for folks from general news about the industry. At the same time, tagging can be tedious when misused. Why on earth, at this blog, would I need to tag this post or any other with “writing”? That is, after all, the focus on the entire blog and its sponsor.

My post has gone on far more than 350 words (it’s at 991 now!), but I think it presents the basics.

The hardest part remains the writing itself. No medium changes that.

Refer to links at this Writer’s Web page for more advice on academic blogging. Good luck with your posts!

Apologies for a late post. I’ve been working on a different deadline, and the Friday afternoon cutoff for a Monday Spiderbyte notice slipped by, well, like a ship in the late afternoon.

Apologies for a late post. I’ve been working on a different deadline, and the Friday afternoon cutoff for a Monday Spiderbyte notice slipped by, well, like a ship in the late afternoon.