I love literary metaphors, especially ones that date their popularity to a work of Shakespeare’s. We have so many–pound of flesh, sound and fury–but this month’s metaphor has an historical origin that predates the play Julius Caesar.

I love literary metaphors, especially ones that date their popularity to a work of Shakespeare’s. We have so many–pound of flesh, sound and fury–but this month’s metaphor has an historical origin that predates the play Julius Caesar.

The OED Online cites “Ides” as “In the ancient Roman calendar (Julian and pre-Julian): the third of the three marker days in each month, notionally the day of the full moon, which divides the month in half, i.e. the 15th of March, May, July, October, and the 13th of the other months.” The Calends (or Kalends)and Nones were the other marker days. You can read more about them here. Now we see where our word “calendar” comes from.

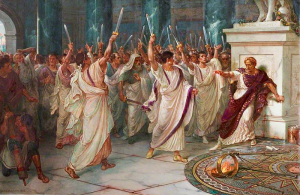

But back to Ides. If every month had them, why are they so metaphorically significant? Julius Caesar met his end in the Senate after a dire warning, here given from Shakespeare’s play:

Soothsayer: Beware the ides of March.

CAESAR: What man is that?

BRUTUS: A soothsayer bids you beware the ides of March.

CAESAR: Set him before me; let me see his face.

CASSIUS: Fellow, come from the throng; look upon Caesar.

CAESAR: What say’st thou to me now? speak once again.

Soothsayer: Beware the ides of March.

CAESAR: He is a dreamer; let us leave him: pass.

Sennet. Exeunt all except BRUTUS and CASSIUS

Julius should have listened better, and kept a keen eye upon his “friends” in Rome. In any case, the metaphor, a lovely one for a time in need of vigilance or a date of reckoning, has fallen out of even learned parlance these days. As with so many fading phrases, it’s a great loss to nuance and history in our language.

When language gets lost or dumbed down, it’s as often our fault as not. I just heard this when the first test passenger for Virgin Galactic, otherwise articulate and precise, described something seen from space as “super super super high def.” Going into space! And all she could manage was an adjective, super, that I consider overused to the point of oblivion. Sir Richard Branson, send me to suborbit. I promise to use more adjectives, many of them printable.

So that’s my challenge for all of you, as Spring arrives. Try some fresh words this Ides of March and every month. After all, as Cassius warns his co-conspirator, “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves, that we are underlings.”

Please nominate a word or metaphor useful in academic writing by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Image credit: There are hundreds of good (and more than a few hilarious) images of the death of Caesar only a click away. This one, a painting by William Holmes Sullivan, comes from Wikipedia Commons and is licensed for Creative-Commons use.