Students delight me when they ask the meaning of a word I use. I do not dumb down my vocabulary for them, though I also do not employ arcane jargon best left to fellow specialists in my field. Asking mentors provides one good method for learning new words. Reading, of course, works even better.

Students delight me when they ask the meaning of a word I use. I do not dumb down my vocabulary for them, though I also do not employ arcane jargon best left to fellow specialists in my field. Asking mentors provides one good method for learning new words. Reading, of course, works even better.

But when I was asked what “paginated” means, for a moment I got taken aback. Not in contempt for my undergraduate questioner but for an increasingly digital world we inhabit, a world that terrifies me because like universities, I see a culture of bookishness as a shield against a Dark Age that might be as close as a few more tragic national elections.

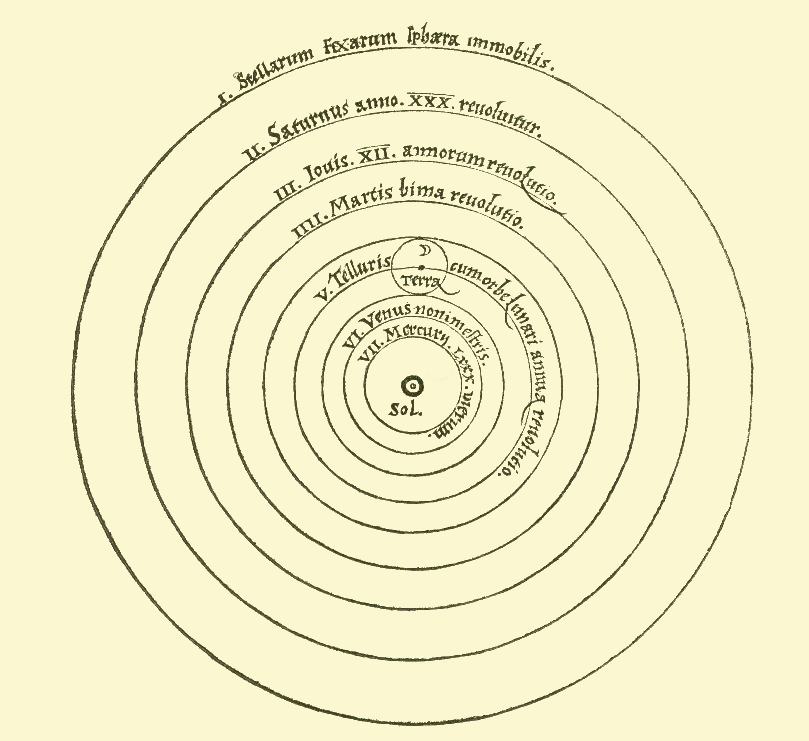

The word “paginate” comes from a post-Classical Latin root, paginare, dating to the end of the last Dark and Middle Ages in the 15th Century.

Modern usage in English for “paginate” dates to the middle of the 19th. That’s not a long time, historically. To paginate means to put a text in order by pages. Nothing more nor less. The OED entry comes across as simply and elegantly as a well designed book.

Now, with real concern I don’t know if the Enlightenment that followed pagination, sparked by printed books, has run its course. Some of my students are anxious about this, understandably, and that brings some comfort. They will have to fix it, as with climate change, racism, and other evils of our era.

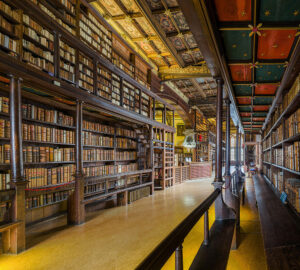

As a reader who knows me can attest, I am a person of the book. Personal and public libraries likewise bring comfort in uncertain times and remind me, a first-generation college student, how tenuous and precious a life of books can be, as well as hard-won. Please do not call me a Luddite–I code poorly and manage a Web server–but what Howard Rheingold called the Amish: a techno-selective.

Like shifting my own gears and working a clutch, a now-arcane art I mastered at age 60, buying, reading, and collecting printed texts puts me close to a technology. Two, really: bookmaking and the language we use to communicate.

While I do read some scholarly and journalistic work on a screen, most all reading for pleasure gets done using paper texts that have page numbers. One odd exception: Rowling’s Harry Potter novels, since I began them that way on my iPad in 20`14 when traveling in Scotland (I’m going to read the fourth installment next summer).

My students, on the other hand, inhabit a different world, a mostly unpaginated world. Even back in 2011, as I reported here, blogs like this one were being read and written less by young people. Incidentally and coincidentally, first-recorded use of “pagination” dates to 200 years before that blog post, a bit earlier than the verb form. One wonders how long a run it will enjoy, now.

So be it. What students do with their free time is their choice. I’m delighted when they read this blog, but faculty, staff, and visitors have long been my audience here. Yet for everyone, the world of ideas demands long-form narrative in many fields and books remain a remarkable technology for delivering these narratives.

How to fight this? When my students do bibliographic word, I make them delve into a few print-only resources, citing their work with page references. Yes, I check every one of those.

More hangs in the balance than we might imagine, retaining even faintly a culture of paginated books. I’m worried enough about paginated media that I’m going to start a new category of posts here for endangered words.

Image source: Duke Humfrey’s Library, Bodleian Library, Oxford University, via Wikipedia.