Ah, homonyms in a time when we are once again becoming an oral culture. Too many of my students neither read enough seriously nor read with care when they are required to do so. Hence, the repeated docking of 10 points (they can get them back) for confusing “whether” and “weather.”

Ah, homonyms in a time when we are once again becoming an oral culture. Too many of my students neither read enough seriously nor read with care when they are required to do so. Hence, the repeated docking of 10 points (they can get them back) for confusing “whether” and “weather.”

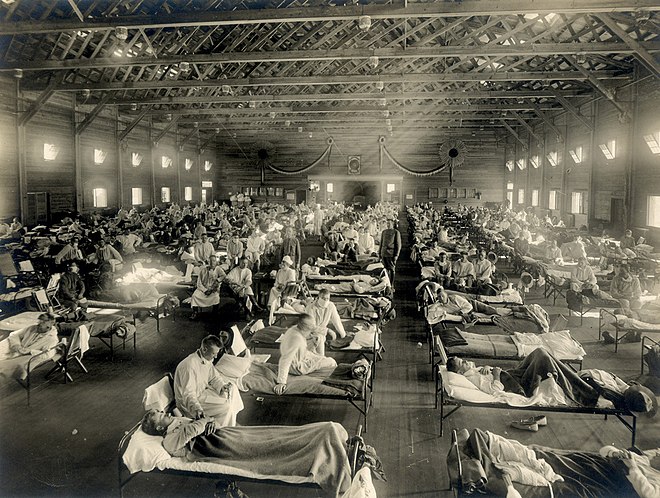

As in Dylan’s song, “you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” It’s blowing an ill wind, for nuance in the language. I think. If so, I cannot stop it with my 10 measly points. But what if these winds blew before? And will blow again? Hence my Mead Hall photo. We are going back to the time of Beowulf, fen-stalking Grendel the monster, and the warlike but helpless Geats that the monster preyed upon.

As we’ll see, there were once two distinct terms in play that now sound exactly alike. So where did our words come from and where diverge? Let’s dip again into Henry Bradley’s The Making of English, (a steal for your Kindle at 99 cents, the one sort of book I like to read on a screen). The philologist notes, in his chapter on changes of meaning, that “[m]ost of the distinctions that exist in spelling and not in pronunciation are between words that are historically different, and when this is so the various spelling usually represent obsolete varieties of pronunciation.”

“Whether” is one of the oldest English words I’ve featured. The OED dates an obsolete adverbial form back to the time of Beowulf, with the Old English term hwæþ(e)re. Leaving that term in the Mead Hall with the brooding Geats, let’s move forward in time a bit, to look over, in your own sweet time, (spelled many different ways) the multiple ways in which “whether” got employed down the centuries. It’s almost maddening to follow the many twists and turns this one ancient word took, until we get to 1819, with Poet Percy Shelley wondering in a letter, “I am exceedingly interested in the question of whether this attempt of mine will succeed or no.”

So am I. Can I teach Gen Z why the words are not interchangeable in writing? Or is it as doomed as Beowulf’s last battle with a dragon? Let’s not go there. What about the weather? Here we have another ancient word, this time from German, rendered in Old English as weder. I suppose when Grendel ventured out into the fens to maim, mangle, and eat Geat, he did his best work in foul weather, and he was able to distinguish the pronunciation of the two terms. The OED notes morphing in how the word got spelled, but like whether, weather (the word, if not the phenomena) settled down by the 19th Century.

What will happen next, round the colossal wreck of whether and weather? I’m no weatherman. I don’t know. Our modern forms of communication lend themselves to encouraging more simplification. Maybe we’ll use one spelling such as “wether” in a century, and listeners will then, as now, know which way the linguistic wind should blow. I and my 10-point penalty will be long gone, either way.

Please send us words and metaphors useful in academic writing by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Mead hall image courtesy of Wikipedia. I really wanted one of Beowulf ripping off Grendel’s arm, but I didn’t know weather whether it would be safe for work.

Rarely to I begin a post with a full definition from the OED, but for this word, I shall:

Rarely to I begin a post with a full definition from the OED, but for this word, I shall: