Every summer, I read something nautical. I’m a mountain and not a water person, but sailing and ships really interest me. The closest I get is from my fishing kayak (and this has been a good fishing year for me). Four years have passed (!) since I did my last nautical metaphor, doldrum.

Every summer, I read something nautical. I’m a mountain and not a water person, but sailing and ships really interest me. The closest I get is from my fishing kayak (and this has been a good fishing year for me). Four years have passed (!) since I did my last nautical metaphor, doldrum.

Part of my interest in ships and sailing involves the riches of vocabulary they bring us. In several books I encountered our rather antique metaphor, another of those terms I’d love to see used more commonly again. As the OED informs us, the term refers to a “belt of calms and light airs which borders the northern edge of the N.E. trade-winds.” Usually the term simply indicates the literal area, even in our time of steam-ships.

The origin of the term remains unknown to the OED editors. The tales of sailors lightening their load by throwing effigies or actual horses overboard seems a stretch to this landlubber, given the animals’ value. Eating them when becalmed and starving? Possibly, according to a writer at Medium.

Metaphorically, our term suits June and early July well for academics. We are deep in our summer projects, and campus is silent of most student noise. Sometimes we have little bursts of activity; the winds pick up, so to speak. In that area of calm between steady winds, Facilities repairs and builds, plans for the year are laid down. It’s my favorite time of year, even though most summer weeks I work from home.

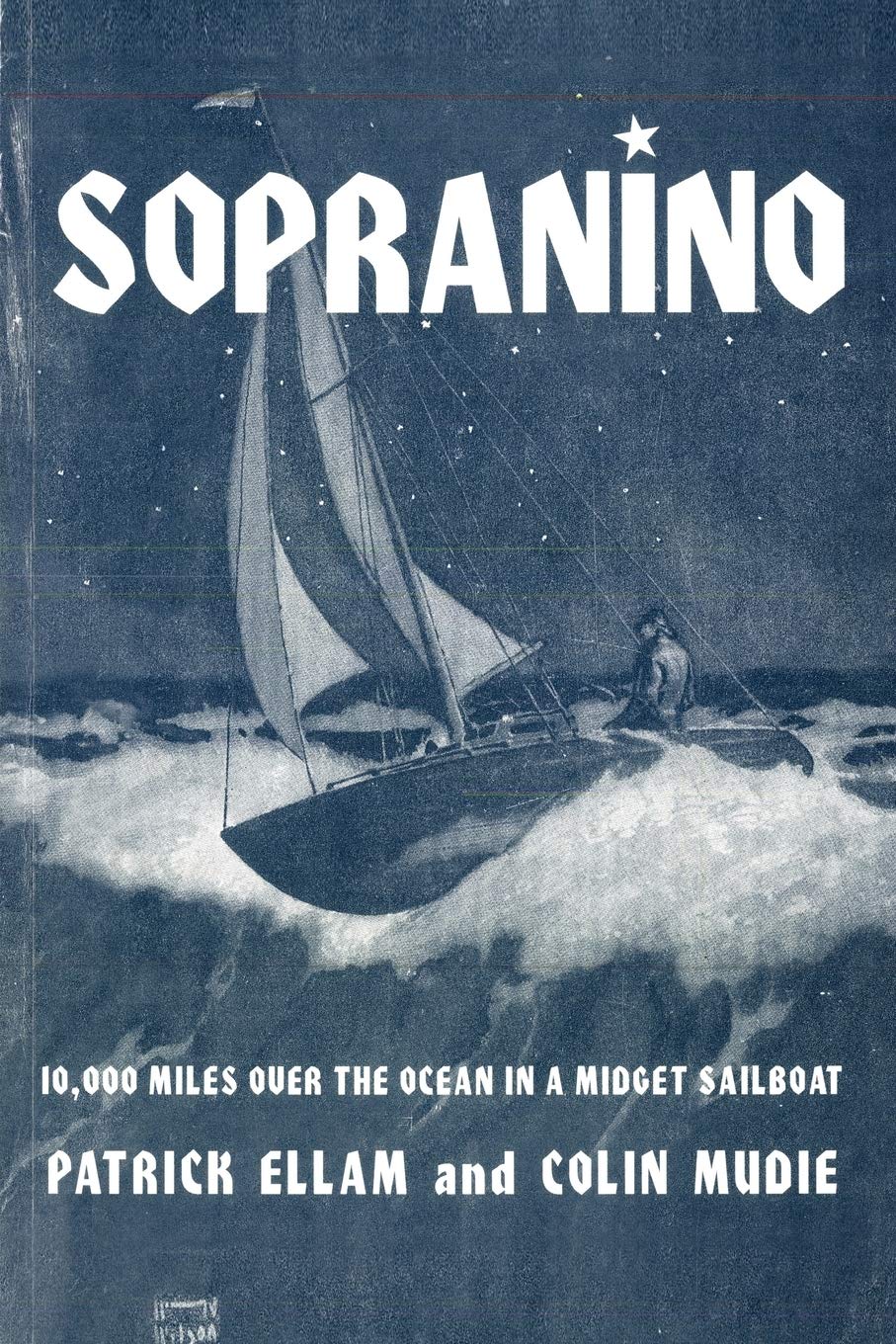

This summer’s read? Sopranino by Patrick Ellam and Colin Mudie. They designed and sailed the world’s smallest ship–a 19′ sailboat rated for ocean travel–across the Atlantic. It’s a great story told in a light, yes, breezy style from a simpler time than ours. They do run into several sudden calms off South America, in the horse latitudes. They also get robbed in Jamaica, but being charmers, content the crooks with a few dollars. The books remains out of print but old copies are easy to find.

As Summer skims along like a fast racing yacht, I’ll post your entries. Do you have a word or metaphor for this blog? Send them to me by e-mail (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Image from the 2011 edition.