Dr. Greg Cavenaugh of Rhetoric and Communications Studies will work with my trainee Writing Consultants this semester. His First-Year Seminar, “Heroes and Villains” is a great topic, but no matter the subject matter, first-years always make the same errors.

Dr. Greg Cavenaugh of Rhetoric and Communications Studies will work with my trainee Writing Consultants this semester. His First-Year Seminar, “Heroes and Villains” is a great topic, but no matter the subject matter, first-years always make the same errors.

So I asked Dr. Cavenaugh for a list. Here is what he sent. Please send me other issues/concerns you have about first-year writing!

No governing claim/thesis at all. Alternately, a governing claim stated only as a question. This more often occurs in reflective writing such as reading journals, but it sometimes appears in more formal assignments. This problem may well stem from the assumption that writing is simply “stating what I think.” Scholarly writing is a lengthy process of crafting and revising an argument; “stating what I think” is at best a first step in the creation of an argument.

Several sentences (sometimes multiple paragraphs) of fluff before the author reaches his/her governing claim/thesis. This may well stem from the notion that scholarly writing is “fancy writing” and that the first few paragraphs of scholarly research are fluff. When a reader is familiar with the norms of the academic field that an author is addressing, it becomes clear that what students regard as “fluff” is actually essential to the author’s argument. The reason that a novice reader views these paragraphs as “fluff” is simple unfamiliarity with the academic discipline and the communicative norms of that interpretive community. In Grad School Essentials, David Shore sums up this concern as, “Get to the bloody point. Please.”

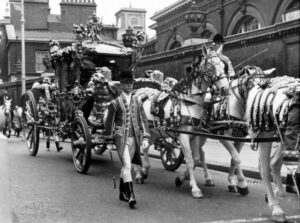

Essid’s note: I call such “fluff” a “March of History” introduction, and it seems to come from public-speaking experience in some cases. You know it: “As soon as humans stood erect, they gazed upon the night sky in wonder. For millennia we have wondered about the Moon. Finally, in 1969 we went there…” would be a typical paper about Neil Armstrong in my FYS, The Space Race. -10 points and a week to cut to the chase with a revision, please!

Paragraphs that run across multiple pages. From the early 2000’s to about two or three years ago, I would ask students, “How long is a paragraph?” and get back a disturbing answer. “Oh, a paragraph is 8-12 sentences long,” students would routinely say. I’m not sure where this definition of a paragraph came from, but it was taught with remarkable consistency for much of the last twenty years. Over the last few years, I am starting to hear a different, more functional answer: “Oh, a paragraph is about 3-4 sentences at least and maybe about 7 sentences at most.” Despite this relative improvement in the perception of paragraph length, I still find students writing “mega-paragraphs,” and those “paragraphs” often (let’s say) start on page 2 and end on page 4. These “mega-paragraphs” usually develop from a lack of clear organizational structure—instead of making one point that leads to another point in a programmatic fashion, the author attempts to say several things all at once.

A lack of explicit reasoning that moves from one concept to the next to programmatically prove a point. This is the broad, structural version of the previous issue. Students may articulate a clear governing claim/thesis that can be reasonably supported, and yet their argument bounces randomly through ideas rather than making a linear case. Of course, good writing sometimes cannot be linear and direct; sometimes authors must take “side treks” in order to guide the reader to the final conclusion. These side treks should never be considered the default for academic writing, however. Instead, writers should build a case like a lawyer in a murder trial. Classic detective-novel reasoning here is good enough for our purposes—in order to prove that Tom killed Jerry, we need to show that Tom had the means to commit the murder, a significant motive for killing Jerry, and the opportunity to commit the murder. If those are the three things that we must demonstrate, then we craft our argument to support those three points, in whatever order best allows for clear movement from one idea to the next.

To extend the analogy, beginning writers often start out showing the Tom had the means to commit the murder, then take a detour into Tom’s character and the horrible things he wrote on social media, then return to the issue of means while confusingly introducing a hint of Tom’s motives, then going into an elaborate forensic analysis of the DNA at the crime scene, then proving that Tom had no alibi, and finally concluding with, “There, as you can plainly see, beyond a shadow of a doubt, Tom killed Jerry.” Note that all of these elements COULD be used in a court case against Tom, including the references to his horrible social media posts. The problem is that there is no clear line of reasoning that helps the reader understand how (for instance) the DNA evidence relates to the question of opportunity (maybe the DNA proves Tom’s alibi is false).

Equating scholarly, formal writing with a stiff, abrupt tone. Good writing can be personalized and can reflect a writer’s sense of style. With the exception of some specific disciplinary audiences, such as writing up a lab report for a physics class, there is no need to sound stiff, inhuman, and impersonal.

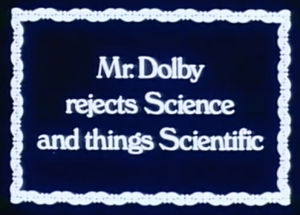

Alternately, equating scholarly formal writing with a loopy, baroque style. Sometimes young writers assume that their goal should be to personalize the material as much as possible, to sound creative and elegant in the manner that associate with “high” scholarship. Often, the remedy is to ask the writer for a “plain English” translation of their ideas.

Commas used everywhere or nowhere. I am not talking here about the occasional miscue of a misplaced comma, and I am not talking about my lifelong support for the “Oxford comma,” which is regarded by some writers as inessential. What I’m talking about here is a systematic inability to use commas correctly. I often find that, at some point, the student was chastised for his/her use of commas, and now the student either avoids commas completely or else throws in commas everywhere, hoping some of those commas land in the right places. For tutors who are not themselves sure about where commas go (which is an understandable issue), note that you can still observe that the writer is avoiding commas or overusing commas, even if you have trouble explaining the grammatical issues.

No awareness of the distinction between plural and possessive. This is just plain annoying: “The heroes actions demonstrate his character.” One hero (“hero’s”)? Several heroes, possessive (“The heroes’ actions demonstrate their character”)? What are you trying to say here?

No attention to verb tense. Also just plain annoying: “Tom enters the room and sees Jerry. Jerry tried to run away, but he slipped and fell, so Tom hits him with a mallet and then escapes before anyone had seen him.” Either write the whole thing in past tense or write the whole thing in present tense. Because students in my academic field must so often write descriptions of actions, such as describing the actions of characters in a film or summarizing the steps involved in a religious ritual, I see this problem a lot.

Section headers used as transitions. I love section headers as a tool for helping the reader intuit the organizational logic of your work. But by themselves, section headers don’t actually transition a reader from one idea to another idea in a way that connects those two ideas. Use a section header and transition sentences.

Sentence fragments produced by years of SMS texting. We’ve all produced incomplete sentences and seen the dreaded “FRAG” comment in the margin of our work. Contemporary first year students are, however, even more likely to produce sentence fragments in my experience. SMS texting allows for and even encourages the expression of partial thoughts on the presumption that the reader is “clued into” the context that makes their partial thought complete. This is especially the case with “meme culture,” where a single image and accompanying text is used as a shorthand for a host of thoughts and feelings that are condensed, almost poetically, down to something that can be sent via text with a few thumb swipes.

Using 50 words to say what can be expressed in only 10. Students often write themselves into an idea, wandering through a ton of words in order to arrive at a useful concept. The revision process should involve rigorous editing to tighten the work.

Essid’s Addendum: “Hand Grenade” quotations bedevil first-year work. Students drop in a quotation without introducing it or linking it to other claims made by follow-up analysis. -10 again and a week to fix it. It amazes me how many neglect to get it done in a week, losing a full letter grade in the process.

Image source: “The Stair Method” by Sage Ross at Flickr.

Two mushrooms walk into a bar. The bartender shouts “Out with you! No plants allowed!”

Two mushrooms walk into a bar. The bartender shouts “Out with you! No plants allowed!”