I suppose this is, like everything else, a post about the pandemic. I’ve been seeing our words of the week in reference to models of learning and college life that are not longer useful, even worn out. Some bold claims are being made that residential education itself may soon be “obsolete.”

I suppose this is, like everything else, a post about the pandemic. I’ve been seeing our words of the week in reference to models of learning and college life that are not longer useful, even worn out. Some bold claims are being made that residential education itself may soon be “obsolete.”

While I doubt that, it seems reasonable to hazard a guess about which practices of ours might be “obsolescent.”

There’s a shade of difference that I knew, however, as a geeky pre-teen obsessed with the history of technology of warfare, in particular The Second World War.

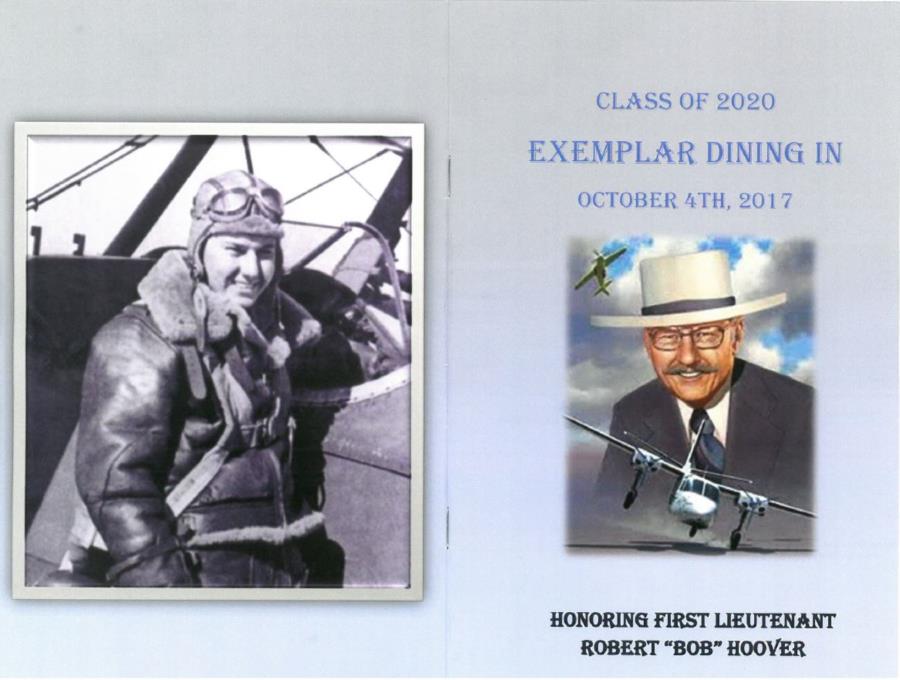

Looking at my home library, there’s a book I read at age 11, Martin Blumeson’s Sicily: Whose Victory? part of a epic series of paperbacks published by Ballantine Books. I think I own about 50 of the titles, and the writing was decent, often by noted historians and with introductions by famous people involved in the actual events from a quarter century before. In the book, there’s a photo with the caption “German flak guns guard obsolescent Italian fighters” with some biplanes in the background.

I heard, and forget the source, that World War 2 began with biplanes and cavalry charges, yet ended with jet fighters and atomic weapons. By war’s end, the two military traditions and their equipment were certainly obsolete, which The OED defines as “out of date.” Yes, a biplane is a flying machine, but not one to employ in combat in an age of jet fighters. The word is a “borrowing from Latin” and dates in the OED’s reckoning to at least the 16th Century. I like that it’s really unchanged in meaning, too. A useful word, that!

As for things that are going out of use, but not gone yet? I have always guessed that fit the meaning of “obsolescent.” Turning again to The OED, I can see that the Ballantine Books series taught me well. This word means “becoming obsolete; going out of use or out of date.” Thus, for my military examples, horses were used throughout the war, but until the struggle against the Taliban, they did not factor into the military planning of any great power. For biplanes, they are with us but as stunt planes or objects of nostalgia.

Funny how, in a time of pandemic, it’s comforting to use examples from a long-ago, if terrible, conflict. Perhaps that’s because we do not recognize what is obsolescent about our way of life until it’s obsolete?

Send your words and metaphors our way all summer, by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Image of Polish cavalryman, 1938, courtesy of Wikipedia.

Linda Hobgood, Director of UR’s Speech Center, ran across this term recently and nominated it. And why am I using a scene from Peter Jackson’s film? Wait for it.

Linda Hobgood, Director of UR’s Speech Center, ran across this term recently and nominated it. And why am I using a scene from Peter Jackson’s film? Wait for it.