Last year, I covered “syllabus” as our word for the first week of classes. It’s one that many students never encounter before arriving on campus. Given the ancient history of universities, there’s no surprise that many words unknown beyond our gates crop up.

Some terms, like “campus,” “curriculum,” or “physical plant” enjoy broader usage, but I could not immediately think of anywhere else I have heard “Registrar” employed. Students learn quickly that our Registrar’s Office does a fine job of setting up enrollment systems, guaranteeing course-credit where credit is due, tallying units of same so a student my gradate correctly. But where did they get their name?

Several British officials have held the title, including one roughly analogous to an American Justice of the Peace; this much I learned from the OED’s entry. Thus any official or office charged with keeping civil or clerical records could be a Registrar. In US parlance, however, at first I could think of only one use, for campus services concerning enrollment, graduation, and official records. Then I recalled that at the last election I saw a reference to our Registrar of Voters, a thankless but essential duty if a democracy is to function well.

Thank a Registrar for your vote getting counted, the diploma hanging on the wall, or the transcript your employer requested. The OED has this usage dating to the early 18th Century. For other meanings, our word goes back to the 16th Century and probably earlier.

So when you call upon the Registrar this semester, tell them you appreciate the assistance: their work makes this place possible as an official, degree-granting entity.

Let me give you a sense of the vital need for such largely invisible services: I wish I had a photo of the UVA Registrar’s vast filing system from the 1980s; they provided the State of Virginia with my official transcript, proving my degree so I could take a tech-writing job for the Department of Corrections. My duties for DOC involved proofreading and digitizing thousands of inmate records for an early database, OBCIS (The Offender Based Correctional Information System), now mostly a footnote in the history of corrections; the data have been merged with other databases, into what I hope remains an accurate set of records.

We had the entire first floor of an office building dedicated to storing paper; we needed only a small conference room to do the OBCIS coding. We managed paper files for over ten thousand incarcerated felons and an equal number out on parole; the files all moved about on an automated retrieval system. The core of this was a giant conveyor belt for floor-to-ceiling file cabinets. If a Parole Board member or the Governor wanted a file, it needed to be available at the counter in no more than a couple of minutes. Peons like me? We waited longer. The facility included advanced fire-suppression technology that did not use water. Loss of records, none duplicated, would have been catastrophic. We’d have lost release dates, psychological profiles, and opinions by members of our Parole Board.

It could be mind-numbing work, but we kept a supply of coffee handy and kept reminding ourselves that mistakes might delay a person’s release or hasten it. In a different DOC job a few months later, I had the wrong inmate show up at my office for a pre-parole interview. He admitted that he got a free ride in a police car and a meal at a different jail. He was a non-violent offender and very affable, but no one believed his story. I gave him a cup of coffee. The next day, we got the right guy in for his chat.

Today, an incorrect entry in an electronic record and be annoying, even damaging, but with backups on and off-site, one hopes that we can avoid chaos.

Addendum for August 28: thanks to reader Marybeth Bridges for this medical reference from the UK, replete with British spellings:

A junior doctor undergoing specialty training under the UK model of graduate medical education. Under the Modernising Medical Careers programme, juniors complete two years of general medical training—the so-called Foundation Years (FY1, FY2)—after which they compete for National Training Numbers (NTNs) and begin specialty training (as specialty registrars), often beginning in the 3rd year after graduating from medical school.

Registrar posts are often described by the year of specialist training expected of the appointee—e.g., year anaesthetic registrar SpR3 is a reasonably experienced anaesthetic trainee.

Please send us words and metaphors useful in academic writing by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Storage system photo courtesy of Police.com. Get one for your files at home! You know you need one!

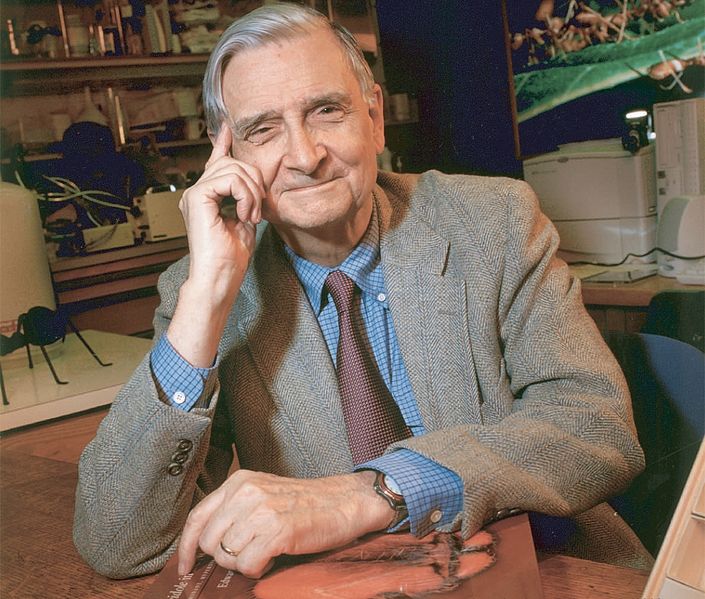

Thanks to Writing Consultant Griffin Myers for this one. It’s a good pick, an older word that came back into academic use after what appears to be a long absence. The term hit my radar screen in the late 90s, when an except of Biologist E.O. Wilson’s book by this title appeared. Wilson sensed that we needed more consilience in our thinking, as a culture. He examines subjects as diverse as a the Humanities, genetics, environmentalism, modern physics, and neuroscience to see how knowledge jumps together in unexpected ways.

Thanks to Writing Consultant Griffin Myers for this one. It’s a good pick, an older word that came back into academic use after what appears to be a long absence. The term hit my radar screen in the late 90s, when an except of Biologist E.O. Wilson’s book by this title appeared. Wilson sensed that we needed more consilience in our thinking, as a culture. He examines subjects as diverse as a the Humanities, genetics, environmentalism, modern physics, and neuroscience to see how knowledge jumps together in unexpected ways.