At the start of a troubled year and the return to classes, I decided to play it safe with the linguistic equivalent of “comfort food.” We could use a bit, true?

At the start of a troubled year and the return to classes, I decided to play it safe with the linguistic equivalent of “comfort food.” We could use a bit, true?

I will soon feature a lineup of timely words, including “sedition,” “impeach,” and “riot,” whose origins and uses may be of interest to both native speakers and English-language learners. Somehow writing about such things as words makes their awful reality more tolerable.

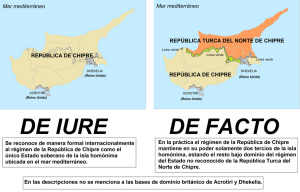

As political events of great import unfold around us, let’s turn for a moment to aiding newcomers to the English language. Consider this: why do we say “he lives in Virginia” or “she lives in Fairfax County” but “I grew up on Parkwood Avenue?”

And we wonder why prepositions are so hard to master. As I discovered while learning Spanish, the best method may be to memorize idiomatic usages and repeat them, frequently, with gentle corrections coming from those who grew up speaking English. Most of these speakers can often tell a learner what “sounds right,” even if we don’t know the rules.

As for rules: the Voice of America’s page about in/on/at shows us that, for position, “in” points to the most general location. Thus, “I lived for a year in Madrid,” while “on” gets more specific, as in “My apartment was on Calle Huesca,” yet “at” gets more specific still, as in “at numero 27 Calle Huesca” or “at the corner of Calle Huesca and Infanta Mercedes.”

Speaking of Mercedes, there’s the exception, where “in” gets quite specific: you can be “in” a car, but you are “on” a larger vehicle or vessel unless you mean you are literally inside a ship, airliner, or the carriage of a train. Then you are indeed “in” the ship, plane, or train.

The pilot is in the biplane, while the wing-walker is on it. Here’s an extended example:

The pilot is in the biplane, while the wing-walker is on it. Here’s an extended example:

We rode in our car to the airport, left it at the extended parking lot, departed on a plane, where I managed to leave my reading glasses in the airliner! We flew to Miami and got on a cruise ship, where we had a cabin on the starboard side at the stern of the ship. We stayed in our room the first two days, as we were too seasick to be on deck. We were very happy to be on dry land again, when the ship was in Jamaica. We docked at Ocho Rios but stayed at a small hotel on the north side of the island.

These little words are harder than they seem!

Then we have figurative uses of these prepositions. Back to my childhood, for a moment. While I did have a mean-tempered neighbor who told me to “go play in traffic!” I can assure readers that I did not actually grow up in the street or on it, in a literal sense.

The shades of meaning here are key for one (and not the only) distinction between “in” and “on.” If you are “in the street” you could be hit by a car. If you are “on the street” the meaning becomes figurative, for walking about in an urban area, unless you happen to fall down. Then you could both be “lying on the street and in the street.” We also refer to the homeless as being “on the streets” at times. Protestors and rioters (here come those future posts) are said to be “in the streets.”

As for time? Another set of distinctions appear for these words when we move to chronology. Again, the VOA page helps a great deal. Consider this example:

At 3:00 am on July 7th in 2020 we saw the peak of the meteor shower.

We’d usually skip the “in” here, inserting a comma for the preposition, but I added “in” to demonstrate the shades of specificity that distinguish our three words. They help to master idiomatic phrases such as “at the stroke of midnight,” “at noon,” “in the afternoon,” “on the day of reckoning,” and so on.

Send words and metaphors to jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu. See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Title image courtesy of me and Photoshop; Creative-Commons licensed wing-walker image from Wikipedia.