Blue is not a feeling we associate with summer, whatever our teenage experiences while listening to The Who’s song “Summertime Blues.” I began thinking about the many figures of speech, as well as single words, we couple with the adjective blue. All of the four really are metaphors, except for one literal use of the term “blue nose.” Read on.

Blue is not a feeling we associate with summer, whatever our teenage experiences while listening to The Who’s song “Summertime Blues.” I began thinking about the many figures of speech, as well as single words, we couple with the adjective blue. All of the four really are metaphors, except for one literal use of the term “blue nose.” Read on.

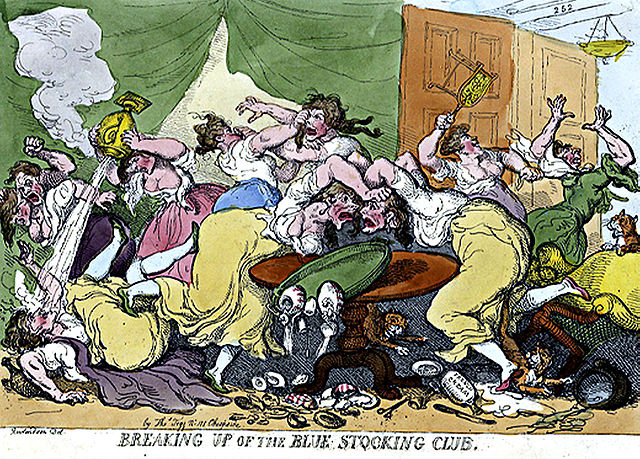

The other day, a friend referred to a well read friend as a “blue stocking.” The Cambridge English Dictionary calls such a person “an intelligent and well-educated woman who spends most of her time studying and is therefore not approved of by some men.” Wikipedia and the OED Online deepen the story, adding a history of an 18th Century literary society called The Blue Stockings. Elizabeth Montagu, literary critic, social reformer and author, started and led the group. It was a difficult time for women who wished to pursue intellectual activities, formally, with no access to higher education.

Today the usage of blue stocking is rare; I’d not heard of it before my friend uttered the phrase. It’s not obsolete, with a currency of four of eight at the OED. Their entry also records a 2001 usage in Vogue that I just love: “Miuccia Prada has..embraced the Waspy,..book-editor look of yore and taken bluestocking style to silk-stocking heights.”

Thankfully, rarity (2 of 8 in the OED’s usage frequency) marks our next word, “bluebeard,” also about women. This, however, has nothing to do with a group of learned ladies but a fiend who marries again and again, only to kill his wives. The OED entry reminds of of Henry VIII’s bluebeard life. It can be used as adjective as well, as in a “bluebeard room” where someone hides something, presumably something grisly. A recent bluebeard from cinema is Robert Mitchum’s character from the excellent (and only) film directed by Charles Laughton, Night of the Hunter. The original Bluebeard (capitalized) came from a French folk tale first published in 1697. That should make us shiver, even on a warm summer day! Bluebeards can apparently be seducers who abandon their lovers, one after another. The verb “to bluebeard” appears, but seems rare.

Are you a blue blood? That is a term I did hear as a child, from better educated peers who talked about the rich families who lived (literally) across the railroad tracks from our neighborhood of modest row-houses. They were the grandees, those “to the manner born,” the would-be aristocrats of our odd little Southern city. As the gentry, they “put on airs.” What why “blue blood”? The OED cites an etymology from the Spanish sangre azul, for the fair complexion of the well-to-do; you can see those veins beneath their milky skin. I prefer skin seasoned by life outdoors.

One thinks here of Goya’s bizarre and unflattering portrait of Spanish nobility. This term is one I’ve long used, so the frequency (3 of 8) at the OED surprised me.

One thinks here of Goya’s bizarre and unflattering portrait of Spanish nobility. This term is one I’ve long used, so the frequency (3 of 8) at the OED surprised me.

And finally, we have “Bluenose,” my favorite of these words (usage frequency is also a 3 of 8 at the OED). As a teen, I loved cartoons that made fun of Puritans. Often they were drawn with blue noses and scowls, making me think them eternally ill in the New England climate. That’s partly true; the OED notes that residents of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were called “Bluenoses” for the cold there. It can also be a type of sailing vessel. In this sense, unlike “bluebeard” or “blue blood” it gets capitalized. Usages appear as “blue-nose,” “blue nose,” and “bluenose.”

Usually the days, the term refers to prudes and puritanical busy-bodies. I am anything but, with my heroes being Beatniks, not busybodies, so I enjoy yanking their choir robes. I ran across the a bluenose recently in a comment on a piece I’d written about a “barn find” car for Hemmings Motor News Daily; I’d made an offhand drug reference in relation to the cars of the early 1970s, and a puritanical reader vehemently objected. In my defense, another reader said that the comments section always “brought out the bluenoses.” I loved that banter, but writers need skins as thick as auto sheet-metal, and we have to bear the dents made by many a bluenose reader.

A cousin of “bluenose” is “blue law.” There’s a false etymology that these prudish laws, aimed at curbing sales of certain products or prohibiting certain work on Sunday, came from their origin when printed on blue paper. Snopes notes that the real origin is their relation to the bluenoses who enacted them.

Have a word or metaphor worth pondering? This blog will continue all summer. Please nominate a word or metaphor useful in academic writing by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Images by Thomas Rowlandson, “Breaking Up of the Blue Stocking Club,” and Francisco de Goya, “Charles IV of Spain and his family,” courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

For June 1, I’m on deadline for my and Brian McTague’s forthcoming book, Writing Centers at the Center of Change. I planned to take a weeklong break on this blog for Memorial Day, but I wanted to know more about the term “deadline.” In any case it serves me well, if a little early, for our June Metaphor. Where did this drop-dead-serious figure of speech first appear?

For June 1, I’m on deadline for my and Brian McTague’s forthcoming book, Writing Centers at the Center of Change. I planned to take a weeklong break on this blog for Memorial Day, but I wanted to know more about the term “deadline.” In any case it serves me well, if a little early, for our June Metaphor. Where did this drop-dead-serious figure of speech first appear?