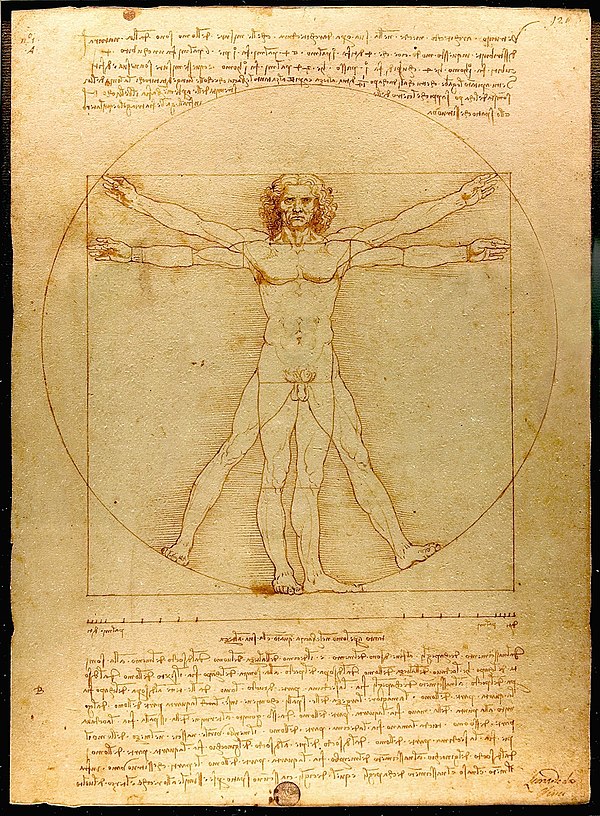

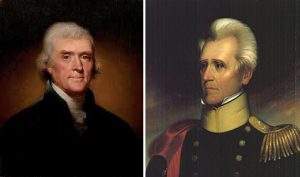

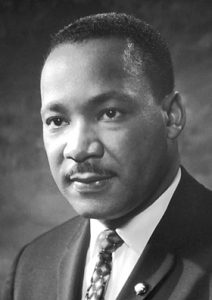

What do these images have in common? They represent sentient beings.

Joe Hoyle, Associate Professor of Accounting at UR, told me that a 2019 goal of his has been to hone his vocabulary. Joe’s nominated word is certainly a good one to employ.

I have used “sentient” incorrectly for years, in in my class about reading science fiction. Often in that genre of fiction, an alien life-form is either an animal or a “sentient” being, meaning (to me) that it acts according to reason, reflection, and logic.

Of course, other stories have aliens wiping humans out and saving other species because humans so seldom employ reason, reflection, and logic. So what do those most sentient of dictionary editors at the OED Online say?

In its oldest sense, “sentient” can include animals or other organisms if they are “capable of feeling; having the power or function of sensation or of perception by the senses.” So for sentience, it would mean responding to stimuli not automatically, but by the senses.

Plants turn to the light, after all, but as stated in an article by Calvi, Sahi, and Trewas (2017), we cannot assume plants are non-sentient because of the “bioelectric field in seedlings and in polar tissues may also act as a primary source of learning and memory.”

Need I feel guilty, then, as I fire up my chainsaw to prune the cedars near my house?

Second-and-third-order definitions of “sentient” include being “conscious” of something. What is consciousness? Animals have it and, perhaps, plants. What of the invisibilia under the microscope?

Please nominate a word or metaphor useful in academic writing by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

image (and it’s a great one!) courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.