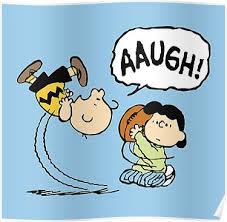

No, you will not find this one in the OED. Yet this term may not only be sadly relevant for November but also it has a mysterious history. Finally, I find it a writerly challenge to post about a curse-word without cursing. Here goes.

No, you will not find this one in the OED. Yet this term may not only be sadly relevant for November but also it has a mysterious history. Finally, I find it a writerly challenge to post about a curse-word without cursing. Here goes.

I ran across our metaphor in Martin Clemens‘s nearly lost classic memoir, Alone on Guadalcanal. He was a British “coast watcher” who stayed behind when Imperial Japan occupied the island. After many tribulations, Clemens and his group of indigenous Melanesian scouts met the US Marines, who landed to liberate the island in 1942.

The Marines were in a tight place, being bombed around the clock, subjected to suicide charges, then bombarded by Japanese warships at night. The see-saw war went on for months, on an island ripe for Malaria, known for venomous snakes, and ringed by waters full of sharks. While in the Marine base, Clemens heard and recorded in his diary a bit of American slang that has continued to our day, for when excrement manages to contact a rotating air disperser.

Or something.

The term often gets dated back to Norman Mailer’s excellent, if gritty, novel of the Pacific War, The Naked and the Dead. Clemens’s usage predates Mailer’s, showing the military origin of the metaphor. Gary Martin of Phrase Finder, where a post appeared about our scatological metaphor, found a recorded use in 1943 and notes a possible Canadian origin from the 1930s.

I’m willing to bet that it goes back to the first USMC unit that had an electric fan in their barracks. If you know enlisted Marines, you can imagine what followed.

Send words and metaphors to jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu. See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Creative-Commons image courtesy of pxfuel.