This old veteran, who served from the late 1940s through the early 90s, recently returned to active duty in news reports about Russia, the US, and China. So I got curious about who first drafted him as a metaphor.

This old veteran, who served from the late 1940s through the early 90s, recently returned to active duty in news reports about Russia, the US, and China. So I got curious about who first drafted him as a metaphor.

One can find uses of the term from as early as the 19th Century, but in the modern sense, it refers to the mostly nonviolent arms race and nuclear standoff between the Warsaw Pact and NATO. Politico has Bernard Baruch stating it in 1947, but I think that George Orwell beat him to the punch. Though Baruch may have popularized the term, Wikipedia has the matter correct here. In a 1945 first-cited reference given by the OED, Orwell wrote in “You and the Atomic Bomb,” of a “permanent state of ‘cold war’ with its neighbours.” And it seemed permanent to us in the 60s and 70s. We could not recall a time of friendship with the USSR or the nation we called “Red China.”

I grew up under the shadow of the Berlin Wall and the mushroom cloud, as I recently told a student anxious about a possible nuclear exchange over the war in Ukraine. Sometimes memories of the fall of the Berlin Wall seem distant, in this new era of major-power tensions.

Then our President at the G20 summit, in a move utterly at odds with his showboating, clownish predecessor, met China’s leader for serious talks. Xi and Biden discussed very sensitive issues, including Taiwan, and our President declared that no new Cold War has begun.

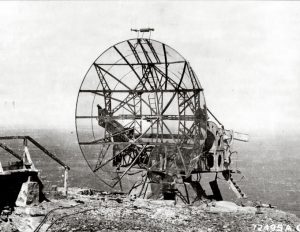

That may be cold comfort to my student, but having lived 30 years with the standoff between the US and Soviet superpowers, I wanted to give some reassurance that sanity prevailed then. May it again. I end with two images: a 1960s interception of a Soviet nuclear bomber by an Air Force F-102, then one that just occurred with a modern US F-22 jet tagging along, a mere 8 miles from US airspace.

Some things change more slowly than our language. Students, if you are reading this, I recommend that you take a few classes about that fraught era.

As things do change, if you have words that have changed, words that have not, or interesting metaphors, send to them in by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

Images courtesy of Wikipedia.