This metaphor gives me the chance to engage in a bit of aviation-geekery. I am also certain I can figure out a Holiday angle, as the season did suddenly come upon me by surprise after a year that dragged on, slowly: a rarity at my age. Such unexpected events can be said to have flown under the radar.

This metaphor gives me the chance to engage in a bit of aviation-geekery. I am also certain I can figure out a Holiday angle, as the season did suddenly come upon me by surprise after a year that dragged on, slowly: a rarity at my age. Such unexpected events can be said to have flown under the radar.

So where did it come from, this term? The OED has many radar-related metaphors we use constantly, and they’d provide good training on the vagaries of phrasal verbs (ones that have a preposition after them) for English-Language Learners. Consider the nuances between these sentences:

- Sorry I missed the meeting. It wasn’t even on my radar.

- Several unpopular provisions of the law flew under the radar until just before a final vote in the Senate.

- Briefly the darling of campus technologists and a few educators, the use of virtual worlds in learning fell off the radar after just a year or two.

“Below the radar” and “under it” pretty much imply the same thing: something slipped in unnoticed. Storms actually do this and so can stealthy aircraft or low-flying ones.

These metaphors started turning up in the 1980s; I find that date unusual, as radar played an enormous role in aerial warfare during the Second World War. The word itself is an acronym for “Radio detection and ranging,” first appearing in 1940, when the United Kingdom used it to great effect to detect Luftwaffe aircraft bound for British cities during the Battle of Britain. At the time, London claimed that their anti-aircraft gunners were doing so well because their eyesight had been improved by eating lots of carrots.

Step back a moment. I recall when that lie, worthy of a Monty-Python skit, still had some currency. The truth of the matter did not fly quite under the radar, as the Germans knew about British radar installations and attacked them. They had radar of their own, as did all the major combatants.

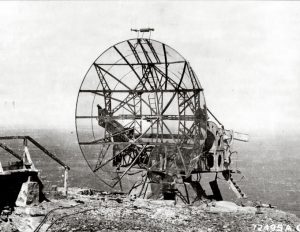

You can find an interesting history of British radar myths at The Spitfire Site, where I borrowed the Creative-Commons image above of a German radar installation. Happy landings!

And it cannot hurt to eat more carrots.

Please send interesting words and metaphors and send them to me by e-mail (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.