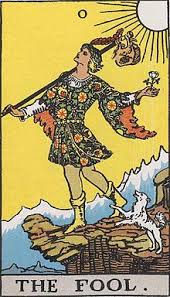

Isn’t it wonderful to have a day dedicated to playing jokes on each other? This post honors April Fool’s Day, a last vestige of festivals from Antiquity such as Saturnalia, where the social order turned upside down.

Isn’t it wonderful to have a day dedicated to playing jokes on each other? This post honors April Fool’s Day, a last vestige of festivals from Antiquity such as Saturnalia, where the social order turned upside down.

I began my hunt for the right word by a simple Google search, to find a synonym for “foolish.” Then, looking at “absurd,” I thought how absurd the nonsense word “google” is, having no etymology I could imagine other than a now-forgotten, and rather foolish, cartoon character. Thinking about Google, as well as using it did, however, give us a word for a very special day. My go-to for the history of words, The OED Online, suggests a dual French and Latin parentage for our word, with absurde indicating something “contrary to common sense.” That 14th Century continued into English, with the OED’s examples dating back as far as the 1500s. In Hamlet, we have this: “Fie, tis a fault to heauen, A fault against the dead, a fault to nature, To reason most absurd.”

My go-to for the history of words, The OED Online, suggests a dual French and Latin parentage for our word, with absurde indicating something “contrary to common sense.” That 14th Century continued into English, with the OED’s examples dating back as far as the 1500s. In Hamlet, we have this: “Fie, tis a fault to heauen, A fault against the dead, a fault to nature, To reason most absurd.”

Unless one is an Adsurdist artist, the absurd is, at best, done deliberately to have fun or make fun of others. Real fools, however, do not recognize their absurdity or even deliberately embark on foolhardy adventures. That sense of reason and absurdity being at odds stands today. That makes “absurd” anything but absurd in formal usage; so many terms drift but this one, like the fool who persists in foolishness, remains delightfully unchanged.

Next week we have a faculty-nominated word from the sciences. It enshrines reason to counteract our foolish pursuits. For now, however, be a bit absurd as you play harmless tricks on friends and family.

Update: This post troubled me because “absurd” does not seem to come from the word “surd” plus the “ab” affix. I found this list of words that employ “ab” in the sense of “away from,” as in “abnormal.” By coincidence, “ab” was the site’s “word root of the day.”

Nominate a word by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Words of the Week here.