Professor Joe Hoyle in the Business school sends us this week’s word, noting “I’ve been reading To The Lighthouse recently and [author Virginia Woolf] uses the word, ‘earwig’ on several occasions. That’s one that I liked.”

Professor Joe Hoyle in the Business school sends us this week’s word, noting “I’ve been reading To The Lighthouse recently and [author Virginia Woolf] uses the word, ‘earwig’ on several occasions. That’s one that I liked.”

I read the novel a decade ago, and Woolfe’s use of language enthralled me, yet that word did not stick, as “noisome” has during my reading of Ackroyd’s London: The Biography. Yet when a word gets employed enough by a talented author, there’s clearly a reason. So why “earwig”? She did not mean the insect reported, without any real evidence, of crawling into a human ear.

Instead, we turn to metaphorical usage of the the term, one that seems to have morphed into “earworm.” Most commonly, that means a piece of music that gets stuck in our heads. How that wig became a worm is beyond the scope of a short post, but it’s an interesting evolution. At one time, as the OED entry proves, “earworm” and “earwig” were synonyms. I like it that in this case, the two words diverged and added nuance to the language.

In its original and derogatory sense, an earwig could be a person who bends your ear to whisper lies or spread gossip to malicious ends. Try as I might, we don’t have a good term in formal English for such a nasty gossip today; Tolkien’s wicked counsellor Wormtongue provides a neologism that I really love. In any case, the obsolete definition for “earwig,” dating from the 15th Century, appears in the OED entry for the insect.

To get at Woolfe’s meaning, she might have been after the verbal definition of our word, the action of being an earwig, to pester someone, to fill their head with wicked insinuations or outright lies. While the usage rarely occurs (2 of 8 on the OED’s usage scale) the concept is very much with us. If someone we call an “Influencer” spreads ridiculous notions or outright evil ideas, they are trying to earwig us. Stop your ears before bad ideas worm their way under your wig…

Please send us words and metaphors useful in academic writing by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

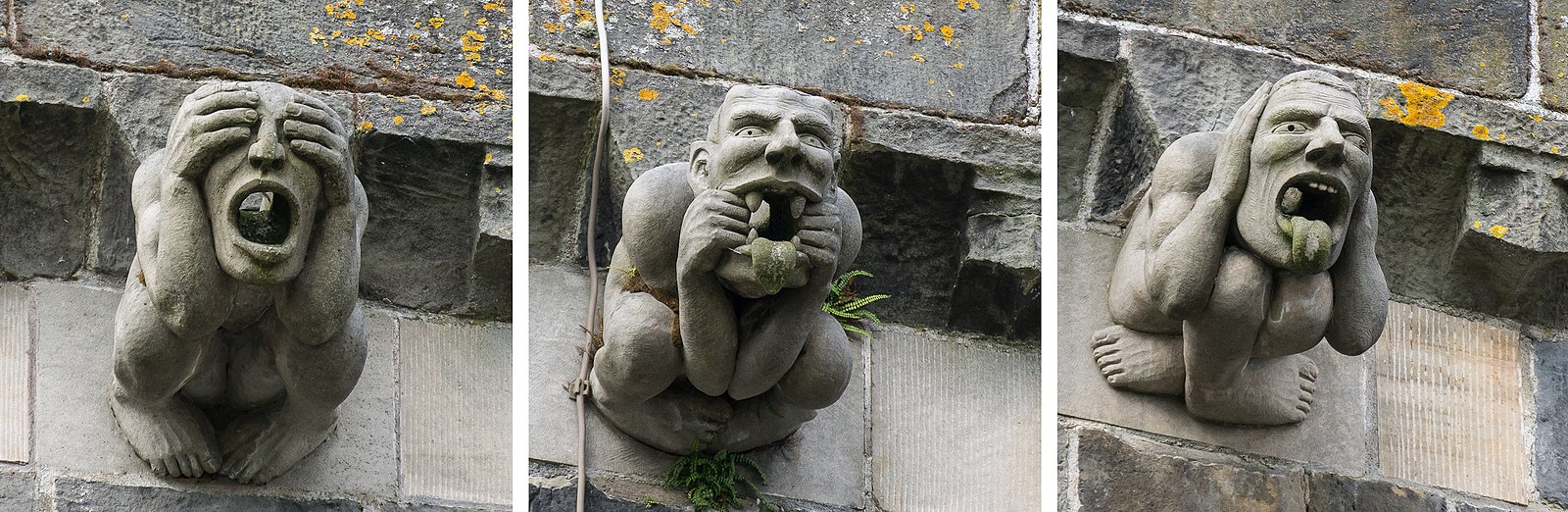

See, speak, hear no evil, courtesy of Wikipedia.

I credit a student in my first-year seminar, “The Space Race,” for this. I’d mentioned the phrase as the way many modern films begin, right “in the middle of things,” without so much as a credit-roll. This is a handy term for studying narratives, in books or films. Often we feel “dropped right in,” which can add both confusion and excitement.

I credit a student in my first-year seminar, “The Space Race,” for this. I’d mentioned the phrase as the way many modern films begin, right “in the middle of things,” without so much as a credit-roll. This is a handy term for studying narratives, in books or films. Often we feel “dropped right in,” which can add both confusion and excitement. This week, UR and VCU hosted writer

This week, UR and VCU hosted writer