The blog has returned from summer break and will feature new posts occasionally until the Fall term begins. After that, I hope to have it back on a weekly schedule.

I don’t think about phonics often. I left it behind in grade school. Then this week, while reading my annual Classical work, I came across an interesting passage. Herodotus covers in great detail the intrigues of the Greek-Persian wars, but one small peacetime event caught my eye. Here’s the passage in David Greene’s 1987 translation:

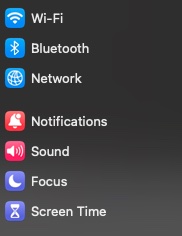

These Phoenicians who came with Cadmus. . . brought to Greece. . .various matters of learning and, very notably, the alphabet, which in my opinion had not been known to Greeks before.

Fair enough, Herodotus. The historian was well aware that until relatively recently, his had been an oral culture. Consider how Homer’s epics and other stories were sung, not written down. But of particular interest to me is Greene’s footnote that this notion “was a traditional Greek belief from very early times, the word for letters being simply phoinikeia, “Phoenician things.” Immediately I saw the word “phonics” in that and decided some other authorities might be needed here.

The OED shows us how modern phonics approaches “learning one’s letters” by means of sound. I learned to read in this manner many decades (!) ago. At the entry linked, you can find other obsolete meanings, but all of them point to fairly modern usage, including the phonetics, that branch of linguistics dealing with speech sounds.

Wikipedia has grown more sophisticated over time, and it helps with this amusing mystery. Its entry cites Herodotus using the Greek term phoinikeia grammata for Cadmus’ gift to the Greeks. That translates as “Phoenician letters.”

Thus sometime during the Enlightenment “phonics” became associated with sound, as in phonetics, phonograph, and maybe the tiny dopamine-dispenser on which you read this, a phone.

Still, we have to thank the Phoenicians, even though theirs was not the earliest alphabet. My father would have been proud. He loved his Lebanese heritage, declaring that our ancestors, the ancient Phoenicians, had been an enlightened and talented people. It could get a little tedious, when dad would rattle off the many things they had invented or done, including finding the New World, while “Europeans were still living in caves.” I’m reminded of the proud Greek father in My Big Fat Greek Wedding, who probably would have insisted that the Greeks invented letters. Both fathers were weak on history after a point, but in the case of letters, we have no less an expert than Herodotus on the side of the Phoenicians. Eat some Hummus bi Tahini and Baba Ganoush (rightly or wrongly, the Lebanese take credit for them, too) and thank Cadmus for his gift. Eggplants are ripe now and I’ll be making some “Baba” over the weekend.

Send in useful words or metaphors, by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Image: Seal inscribed in the Phoenician script, from Wikipedia.

Let’s end a dark year on a happy note. Do you feel euphoric that 2023 has ended? I sure do.

Let’s end a dark year on a happy note. Do you feel euphoric that 2023 has ended? I sure do.