Today’s word comes to us courtesy of Cheryl Huff, on the faculty of our School of Professional and Continuing Studies. The word has cousins I use at times in my teaching: Anthropocentric for a human-focused view of the word, Anthropocene for the new epoch of Climate Change and other human-caused ecological changes, many but not all of them tragic for us and other species.

Today’s word comes to us courtesy of Cheryl Huff, on the faculty of our School of Professional and Continuing Studies. The word has cousins I use at times in my teaching: Anthropocentric for a human-focused view of the word, Anthropocene for the new epoch of Climate Change and other human-caused ecological changes, many but not all of them tragic for us and other species.

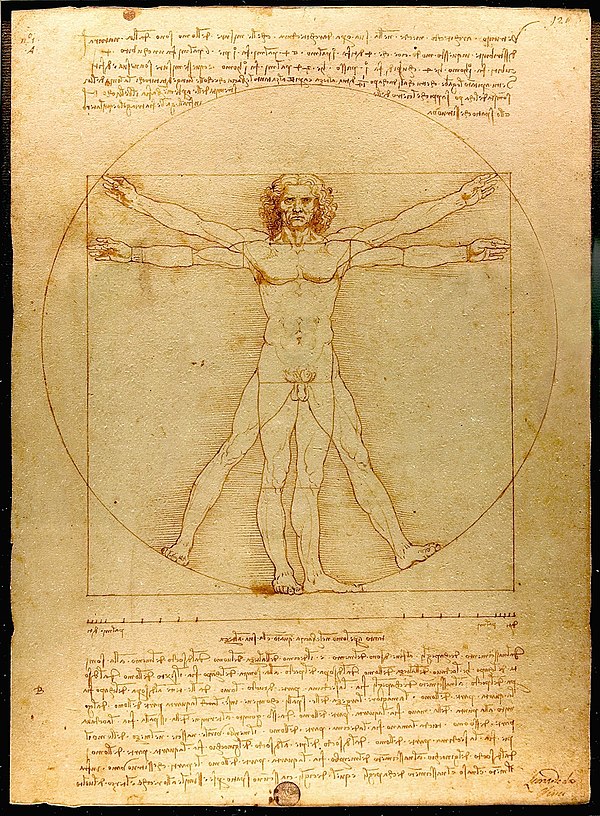

The root of all of them, “anthropo-” comes from Greek and Latin, meaning something relating to humans. Thus anthropomorphic is something to which we ascribe human characteristics. It can also be something that has a human form, as do some robots.

We make animals anthropomorphic constantly; consider the 2005 documentary film March of the Penguins, Disney’s animals, Geico’s talking Gecko, or Carfax’s Fox. Foxes are “wise,” right? Deer, innocent and loving? Perhaps we do this partly out of guilt over what we are doing to them and their natural habitats in the Anthropocene? Or perhaps we simply like making humans the measure of all things?

If we are indeed “the measure of all things,” as went the old cliche coined by Protagoras of Abdera (the phrase is now fresh again, from disuse in our times of shallow language, where “Super” is our most popular, and most mindless, adjective), this week’s word is the one for our “all about us” time.

Please nominate a word or metaphor useful in academic writing by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Image credit: Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci, courtesy of Wikipedia.