I’ve been thinking of Cornell University lately, the site of a first-year seminar program that heavily influenced my thinking about first-year education at Richmond.

Instead of having fond memories of my three visits to Ithaca, lately I’ve also been thinking about the three apparent suicides on the Cornell campus.

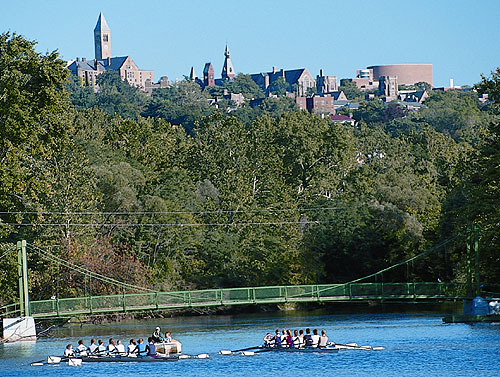

Bodies were discovered in the bottom of the gorges–huge canyons, really–that cross Cornell’s grounds. The image above shows the lowest of many foot bridges; on the bluffs above the bridges cross gorges that are perilously deep.

There have already been six deaths on campus ruled as suicides, not including these three who presumably jumped into the gorges.

Later in life, it’s difficult to comprehend the stress that makes a young person do such a tragic and, finally, selfish thing. Encountering suicide in person, however, is life-altering. In my second year as a UVA undergrad, I recall coming back to Monroe Hill’s dorms to find police on the scene. An electrical-engineering student had electrocuted himself by wiring his body to his room’s air-conditioner. For the first time in our self-centered lives, most of us came face to face with the reality of death.

Richmond does not have an engineering program, where students often take 6, even 7, classes per term. I roomed with an engineer in my third year, and the workload he faced was simply excessive. The goal early in the program was to weed out many students, and luckily–I think now–I got weeded. But even at Richmond, faculty and students may not realize the demands we place upon each other. I grow concerned that we are only a year or two away from a tragedy on our campus as well.

Faculty at Richmond could do more by assigning less busy work, shorter readings, and shorter papers. At the same time, that reduction in workload needs to come with a clear message to students: “I will be asking more of you.” I’ve tried this in a limited way, and while I recapture some free time, and my students appear to be doing better projects at the end of the terms, they place enough emphasis on the grades they get to worry me.

Students need to understand–and this probably could be emphasized more effectively in orientation for first-years–that not everyone gets an A at Richmond, that a B or C will mean little, in isolation, to future employers, and that faculty are not understanding when a student places friends or social activities ahead of coursework.

This proposed attitude falls into a generation gap. Millennial-generation students have been studied extensively, and one apparent characteristic is their desire to do meaningful work on a schedule that pleases them. They crave constant assessment and demand both service from authorities and continual guidance. At Richmond, too often, they exhibit a strong sense of entitlement and treat the university like a product they have purchased. All of that grates on many faculty, especially those like me who believe that failure is a teacher and self-reliance the best guide in life. Yet “I’m confused; what do I need to do?” could be the mantra of Millennials, just as “Suck it up and do it yourself” was–well, is–the mantra of my fellow Gen-Xers. Circumstances from the early 70s onward taught many in my age cohort that life is, indeed, hard. We missed the late 1960s and its culture of bliss.

I’m not that callous, usually, but often I find myself telling a student who wants more from me “you cannot have that” or “that’s not A work.” Many, especially in the first year, have never been told this before.

Often, I worry about the consequences. Yet the world is not made for us, whatever well intentioned but coddling parents claim when they, in effect, tell a child “you are wonderful, and always will be. You can be anything you wish.” Xers had a different lesson; we older ones had distant and “tough love” parents. “You have no sense at all” and “life will teach you” were common messages among my friends’ and my parents. Younger Xers often had parents who had divorced; as children many led “latchkey” lives. That was rare among my friends, and all of us, after a time of rebellion, came back to love and honor our parents when they, in old age, most needed our help.

Yet Millennials now share something with Xers: graduating into a world with economic turmoil and no guarantee of lifetime employment, something only the oldest Boomers can recall.

If college should be a place to prepare students to think for themselves, to cope with adversity, and to broaden their intellectual horizons, are we Xer and Boomer faculty doing the best job? Or, perhaps, making the lessons too hard for young people who are not able to cope?

We all need to talk more about it, and change our expectations.

Joe, I have had both the younger generation students in my leadership classes at Jepson as well as the older generations in the School of Continuing Studies. In both groups, there are students who have unrealistic expectations regarding the grade they feel they deserve€”even when they don’t. You wrote, “. . . and change [reduce]our expectations.” As you know, I have very high expectations of my students in the quality of their research papers, both on an undergraduate level and a graduate level. Rather than lowering my requirements and expectations, I have worked over the years to set the students up for success. This is accomplished by breaking their semester-long research paper into four sections, or chapters (Introduction, Research of the Literature, Application, and Conclusions), and then requiring that they turn in their chapters for marking and grading throughout the semester. I assign points and a grade to each of their chapters as they are turned in, and then, at the end of the course, I review, mark, and grade the final paper as a whole. I take the grades of the individual chapters and their final paper and calculate a final grade. With this process, I can supply the students with on-going feedback throughout the semester (they also are able to seek early help from the Writing Center), maintain my high standards, and help the students achieve their academic goal. In is often the case that when a student turns in Chapter 1 (and even Chapter 2) of his or her paper, the grade received is a “C” or even a “D.” At that time, I tell the students not to worry, that to purpose of all the “red ink” on their paper is to provide them with feedback so they can succeed in the end. Most do. I cannot recall any student making less than a “B” on their final paper. And, they earned that grade!

Best always,

Dick Leatherman

Dick, I think the process you describe works well for the types of students I describe, far better than a single high-stakes grade at the end of term.

These suicides are tragic but they are nothing new – just ask MIT.

http://chronicle.com/article/MIT-Settles-High-Profile/36818/

A culture of frantic competition, mechanical production and inhuman measurement can expect little else, especially when these values can come from the top – as they often do in the academy.

It may be time for a thoughtful and extensive discussion about pedagogy and the purpose of education. Is it all just about competition, production and score-keeping? When competition trumps collegiality and score-keeping gains inordinate emphasis the joy of learning is diminished and academic community suffers. We’ve seen that here at UR in the lack of intellectual discussion outside of class and the weekend binges after five days in the library.

It’s not a matter of having no standards, but of applying that technology of assessment in a more thoughtful and flexible way. It’s about remembering that we are humans, not machines. It’s also about appreciating and learning from the diversity of knowledge systems, perspectives and ways of knowing instead of hunkering down behind disciplinary lines cranking out products and tallying scores with our students.

Our most important issues are not about pressured production and scoring.

Our most important issues are about creating collegial community.

Working for a healthier academic community might encourage students to put their grades in perspective and engage more holistically and enthusiastically in an education that is more about devotion and delight than drudgery and dread.

Agreed, Lee. But how do we change student minds when they buy into the culture of constant assessment?

The “top” on this campus is certainly not our new President or Provost; I see in them a new culture of student engagement beyond the campus gates. That’s a start.

Yet how do we get our students to reassess their own use of time, where every moment of the day seems scheduled, often for non-academic socializing online?

I wondered that as I walked into the building today, passing students who look down at their phones, texting as they (try to) walk across campus.

And no one seemed to notice the dogwoods in blossom except me.