I’ve been thinking of Cornell University lately, the site of a first-year seminar program that heavily influenced my thinking about first-year education at Richmond.

Instead of having fond memories of my three visits to Ithaca, lately I’ve also been thinking about the three apparent suicides on the Cornell campus.

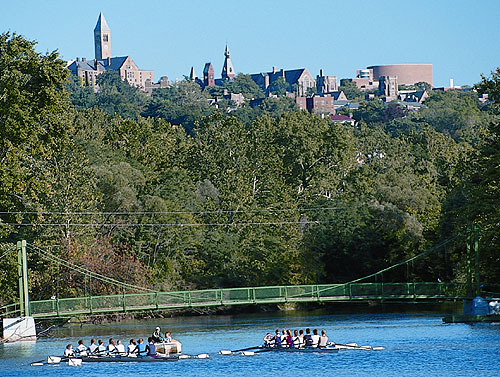

Bodies were discovered in the bottom of the gorges–huge canyons, really–that cross Cornell’s grounds. The image above shows the lowest of many foot bridges; on the bluffs above the bridges cross gorges that are perilously deep.

There have already been six deaths on campus ruled as suicides, not including these three who presumably jumped into the gorges.

Later in life, it’s difficult to comprehend the stress that makes a young person do such a tragic and, finally, selfish thing. Encountering suicide in person, however, is life-altering. In my second year as a UVA undergrad, I recall coming back to Monroe Hill’s dorms to find police on the scene. An electrical-engineering student had electrocuted himself by wiring his body to his room’s air-conditioner. For the first time in our self-centered lives, most of us came face to face with the reality of death.

Richmond does not have an engineering program, where students often take 6, even 7, classes per term. I roomed with an engineer in my third year, and the workload he faced was simply excessive. The goal early in the program was to weed out many students, and luckily–I think now–I got weeded. But even at Richmond, faculty and students may not realize the demands we place upon each other. I grow concerned that we are only a year or two away from a tragedy on our campus as well.

Faculty at Richmond could do more by assigning less busy work, shorter readings, and shorter papers. At the same time, that reduction in workload needs to come with a clear message to students: “I will be asking more of you.” I’ve tried this in a limited way, and while I recapture some free time, and my students appear to be doing better projects at the end of the terms, they place enough emphasis on the grades they get to worry me.

Students need to understand–and this probably could be emphasized more effectively in orientation for first-years–that not everyone gets an A at Richmond, that a B or C will mean little, in isolation, to future employers, and that faculty are not understanding when a student places friends or social activities ahead of coursework.

This proposed attitude falls into a generation gap. Millennial-generation students have been studied extensively, and one apparent characteristic is their desire to do meaningful work on a schedule that pleases them. They crave constant assessment and demand both service from authorities and continual guidance. At Richmond, too often, they exhibit a strong sense of entitlement and treat the university like a product they have purchased. All of that grates on many faculty, especially those like me who believe that failure is a teacher and self-reliance the best guide in life. Yet “I’m confused; what do I need to do?” could be the mantra of Millennials, just as “Suck it up and do it yourself” was–well, is–the mantra of my fellow Gen-Xers. Circumstances from the early 70s onward taught many in my age cohort that life is, indeed, hard. We missed the late 1960s and its culture of bliss.

I’m not that callous, usually, but often I find myself telling a student who wants more from me “you cannot have that” or “that’s not A work.” Many, especially in the first year, have never been told this before.

Often, I worry about the consequences. Yet the world is not made for us, whatever well intentioned but coddling parents claim when they, in effect, tell a child “you are wonderful, and always will be. You can be anything you wish.” Xers had a different lesson; we older ones had distant and “tough love” parents. “You have no sense at all” and “life will teach you” were common messages among my friends’ and my parents. Younger Xers often had parents who had divorced; as children many led “latchkey” lives. That was rare among my friends, and all of us, after a time of rebellion, came back to love and honor our parents when they, in old age, most needed our help.

Yet Millennials now share something with Xers: graduating into a world with economic turmoil and no guarantee of lifetime employment, something only the oldest Boomers can recall.

If college should be a place to prepare students to think for themselves, to cope with adversity, and to broaden their intellectual horizons, are we Xer and Boomer faculty doing the best job? Or, perhaps, making the lessons too hard for young people who are not able to cope?

We all need to talk more about it, and change our expectations.