Thanks to Kim Chiarchiaro, of the Modlin Center For the Arts, who nominated this wonderful word. We see the word in names of bars, unusually, and not the sort where I want to order a Martini (somewhat dry, Hendricks Gin, dash of bitters, clean not dirty, olive not lemon, shaken and VERY cold, thank you). Try that on a server or bartender in a bar named Shenanigans. You might get punched out.

Thanks to Kim Chiarchiaro, of the Modlin Center For the Arts, who nominated this wonderful word. We see the word in names of bars, unusually, and not the sort where I want to order a Martini (somewhat dry, Hendricks Gin, dash of bitters, clean not dirty, olive not lemon, shaken and VERY cold, thank you). Try that on a server or bartender in a bar named Shenanigans. You might get punched out.

Yet beyond that dark vision, the word has a Gaelic sound. I asked the robotic brain at the OED, and found “unknown origin.” Now we have a mystery. The definitions are also delightful, including “Trickery, skulduggery, machination, intrigue; teasing, ‘kidding’, nonsense; (usually plural) a plot, a trick, a prank, an exhibition of high spirits, a carry-on.” The OED records first usage as 1855.

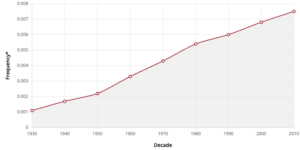

The word might be a bit informal for student work, but I’m thinking that it could be of use to scholars describing several rascals, past or present, who influenced public events. Have shenanigans increased in the past century? I am not certain, but the usage of the term has skyrocketed, from 0 instances in 1870 to just under .05 instances per million words in 1930 to .25 per million in 2010.

Shenanigans may also be on the rise.

This blog will continue all year, so send words and metaphors of interest by e-mail (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or by leaving a comment below. Also let us know if you would like to write a guest column.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia, from the University of Tulsa’s alumni who placed a memorial stone to celebrate “wonderful memories of their college days, including their participation in many shenanigans.”