Here comes a word we often hear but rarely think about when we use it. When I think of “scruples,” I have always imagined someone like Dame Maggie Smith’s character from Downton Abbey, who had more scruples than teacups.

Here comes a word we often hear but rarely think about when we use it. When I think of “scruples,” I have always imagined someone like Dame Maggie Smith’s character from Downton Abbey, who had more scruples than teacups.

Griffin Trau nominated our word; he graduated in December, double majoring in Leadership and International Studies. Since then, he has enrolled in UR’s Master of Liberal Arts program and has one more year of eligibility on our Football team. According to Griffin, “This one is interesting for its root in Latin scrupus meaning ‘small pebble,’ or more figuratively ‘anxiety.’ The word is sometimes used in its historic sense in landscaping for the small pebbles used in driveways, paths, or buffer zones…you know, the ones that always end up in your shoes (that might be how the Romans came up with anxiety).”

In 2009, I walked the remains of a Roman road in Yorkshire, and it would make me anxious to think of little rocks in my sandals with miles to go to reach the next vicus or oppidum. In fact, my reading tells me that Roman roads were amazingly maintained. I’d doubt too many scruples vexed travelers. Yet travelers today take their scruples with them, such as refusing to eat certain foreign foods or, in a gaff I long ago made in a pub, tipping where a local culture does not accept gratuities.

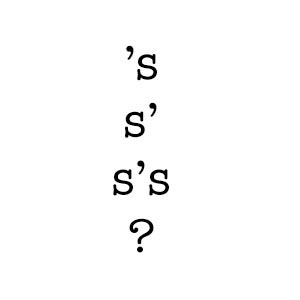

How we went from pebbles to moral or ethical sensibility is anyone’s guess. OED Online gives a first use as a noun, meaning a very small unit of measurement, from 1382. That appears to have been lost, as well as its use as a verb. In that case The OED traces it to 1627, meaning to hesitate based on a moral or ethical principle. It also had a broader meaning to hesitate or doubt, usage that seems to have faded completely today. A fleeting adjectival usage appears as well, scrupling. Let’s not descend further into this as it would be, at best, a scrupling pursuit.

Proper usage today would be as follows, “She was a Countess from a well regarded English family, and she had many scruples about who should be admitted to her inner circle of associates.” Another native of England, Alfred Hitchcock, noted that “There is nothing to winning, really. That is, if you happen to be blessed with a keen eye, an agile mind, and no scruples whatsoever.”

Another native of England, Alfred Hitchcock, noted that “There is nothing to winning, really. That is, if you happen to be blessed with a keen eye, an agile mind, and no scruples whatsoever.”

A less morally fraught use would involve paying attention to detail, as with “After someone broke into his unlocked car, John became scrupulous about making sure he locked the car doors every night.”

Think of the two words we still associate with this Latinate antiquity: scrupulous and its shiftless sibling, unscrupulous. For the verb, I would scruple to use it in a modern sentence. That’s a pity. “Scruple” has a rich history and losing its verbal form robs the language of richness, since it adds a moral sense to our hesitation or anxiety.

That said, I am no scrupulous guardian of the past. Changes to our language as often enrich as impoverish. Yet I have scruples about many words we lose, for with them a scruple of nuance can vanish; it is the greatest thing I fear as our language changes.

See all of our Words of the Week here.