You may be old enough to recall a Chiffon Margarine advertising campaign featuring a woman dressed like an Earth-deity and the motto “It’s not nice to fool Mother Nature.”

You may be old enough to recall a Chiffon Margarine advertising campaign featuring a woman dressed like an Earth-deity and the motto “It’s not nice to fool Mother Nature.”

I agree, though margarine never fooled me. I love cooking so bring on the butter, lard (for pie crusts), avocado oil, and olive oil. Otherwise, get out of my kitchen.

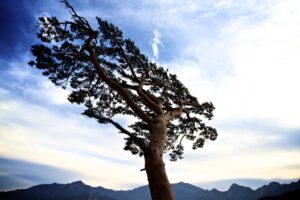

So where did the phrase Mother Nature come from? When was it first coined? The OED is wonky today, giving lots of page errors, but I detect two entries, with one giving a first recorded use of 1390. That means three years before the birth of Gutenberg, so it merits some attention. The problem with this usage, from Chaucer’s Physician’s Tale, comes from the lack of “Mother.” The teller does relate nature to a female deity, but that association goes back to a time not simply before printing but before writing itself.

The same entry gives a date of 1500 for “Dame Nature,” so we clearly see a pattern emerging. Not until 1962 does the OED replace “Dame,” perhaps from midcentury US usage as a belittling term for women, with “Mother.”

The second entry in the OED helps a great deal with our etymology, with instances of “mother nature,” without capital letters, reaching back to 1525.

As for Chiffon? The current owner of the brand discontinued US and Canadian distribution back in 2002, as Wikipedia informs me. Mother Nature had the last laugh. While I don’t think we have an actual angry goddess lashing out at puny homo sapiens who do so much harm to our ecosystems, pause a moment to pay some respect. With a real winter this year (which I love) it could seem that Mama ain’t happy with us. Or is it Papa? Old Man Winter is another metaphor worth our while (and for next year).

Meanwhile sit back, slow down, stay home if you can, enjoy the quiet ferocity of a snow-storm. It’s not nice to fool around with Old Man Winter, either.

If you think of any words or metaphors to share with the community in 2025, send them to me at jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu or by leaving a comment below.

That call for content includes updates and corrections. Regular reader Michael Stern gives us some clarity on our recent word of the week, inure:

“I have been a practicing attorney for more than fifty years and I have never seen the word inure spelled ‘enure.’ If I ever did, I probably would have thought it to be a spelling error.”

Excellent feedback. I always welcome it!

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.