Okay now, this post my have something to do with politics, but I’m not about to accuse anyone of sedition or try to wrangle a working legal definition. I will report what The OED and US law say. You then can peruse and decide.

Okay now, this post my have something to do with politics, but I’m not about to accuse anyone of sedition or try to wrangle a working legal definition. I will report what The OED and US law say. You then can peruse and decide.

We are going to hear “sedition” a great deal in coming months, also “seditionist,” a word last employed regularly in the late 1860s. “Treason” may also crop up.

As always, the OED provides a first stop. The second definition there, listed as “now rare” may well give us pause, as it will likely be employed in investigating and prosecuting those involved in or encouraging the recent riot at the US Capitol: “A concerted movement to overthrow an established government; a revolt, rebellion, mutiny.” Add to that the second definition, “Conduct or language inciting to rebellion against the constituted authority in a state” and I think we are nearly done with what the term means.

As to its origin, look back to French, other Romance languages, and Latin. The word has a long-term life and, sadly, history of examples for good and ill (against tyrannies and governments we might admire).

Soon in popular discussion the word “treason” will also be bandied about. I had assumed that it differed from sedition in that it involved supporing a foreign enemy.

What’s the difference, in terms of definition? the sense from this official document in the House archives is that treason applies to someone who “owing allegiance to the United States, levies war against them or adheres to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort within the United States or elsewhere, is guilty of treason and shall suffer death, or shall be imprisoned not less than five years and fined under this title but not less than $10,000; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.

“Seditious conspiracy” has a different explanation and set of penalties for two or more people who “conspire to overthrow, put down, or to destroy by force the Government of the United States, or to levy war against them, or to oppose by force the authority thereof, or by force to prevent, hinder, or delay the execution of any law of the United States, or by force to seize, take, or possess any property of the United States contrary to the authority thereof, they shall each be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than twenty years, or both.”

There we have it. A great deal of legal action is soon to hinge upon these definitions, as well as which words and actions encouraged violent action or knowingly delayed the “execution of law” in Washington and elsewhere. Learn more about a recent (and half-forgotten) sedition trial of white supremacists here.

These are indeed momentous times, and if you have words or metaphors worth exploring, send them to jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu.See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

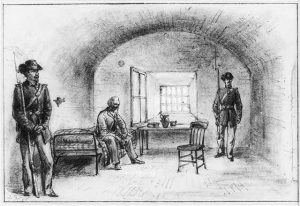

Alfred R. Wauld’s sketch of Confederate President Jefferson Davis imprisoned at Fort Monroe. Davis was charged with treason, not seditious conspriacy. Image courtesy of Wikipedia