Yes, I know it is two words, but you will hardly ever encounter this phrase or its counterpart a posteriori outside academia. Inside it, the Latin term speaks volumes and appears often enough to merit recognition in the blog. The phrase occurs as adjective and adverb. I often run into it, casually, as a noun. That usage does not appear in my references (but I like it anyway).

Yes, I know it is two words, but you will hardly ever encounter this phrase or its counterpart a posteriori outside academia. Inside it, the Latin term speaks volumes and appears often enough to merit recognition in the blog. The phrase occurs as adjective and adverb. I often run into it, casually, as a noun. That usage does not appear in my references (but I like it anyway).

I first puzzled over a priori concepts (and had more than a few of them toppled)in the early 1980s, when I was an undergrad at The University of Virginia. As I came to understand it then, the term meant “principles we assume to be true with out any further questioning,” an idea that I came to see as fundamentally at odds with academic inquiry. A priori ideas were, in my graduate program at Indiana heavy with postmodern literary theory, lampooned.

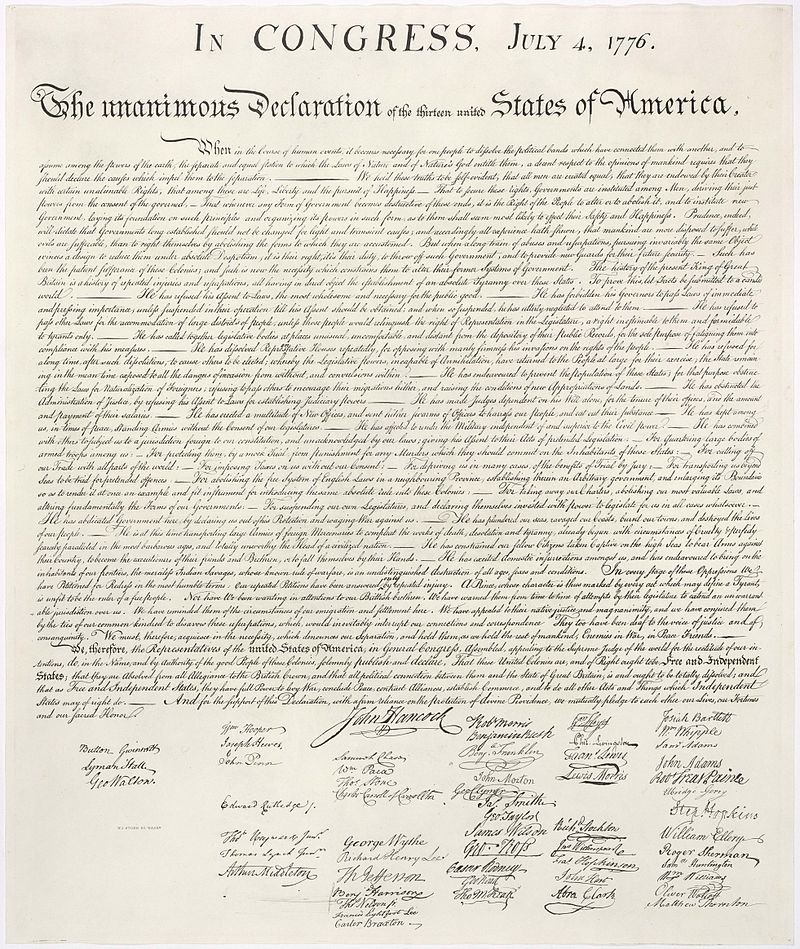

I suppose this a priori statement would get the founder of UVA, Thomas Jefferson, in trouble were he to write in an essay for some of my grad-school classes:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

That Declaration gave us one of the most famous a priori statements in recorded history and began a revolution that one hopes has not ended. But wait. It appears that I need more schooling before I make any claims a priori. I assumed something, and as a student once said in class, ” ‘assume’ makes an ass of ‘u’ and me.”

When I open the pages of The American Heritage Dictionary, my sense of our phrase comes third. Instead, the reference book gives “proceeding from a known or assumed cause” pride of place. The OED Online puts my sense of a priori second, as “in accordance with one’s previous knowledge or prepossessions.” The dictionary also provides a clear 1862 example, “Reason commands us, in matters of experience, to be guided by observational evidence, and not by à priori principles.”

We have lost the accent over the “a,” but I lost more in my reasoning without further investigation. Both reference works imply that a priori ideas do not provide the final word for anything. They are, instead, merely presuppositions for making future claims. That works well with fundamental principles of academic reasoning. H.W Fowler’s classic A Dictionary of Modern English Usage links a priori reasoning to deduction. Mr. Holmes would be proud of us.

A priori reasoning works well outside revolutionary manifestos, the Humanities, or detective work; it is, in fact, essential in the natural sciences. In physics, bodies near the Earth fall at 32 feet per second per second. It was not until Galileo’s era that we came to understand how gravity is related to the mass of a planet and would not be the same on other heavenly bodies. Empirical evidence followed. That new scientific principle became, then, a new a priori concept for those working in the field.

With the end of the semester nigh, consider the a priori concepts you have had challenged or overturned in your life’s journey. More will follow, a posteriori when learning new ideas. I leave that up to the reader to learn, along with the meanings of a posteriori.

This blog will continue all summer, so nominate a word by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Words of the Week here. If you want to read more about whether Sherlock Holmes employs deductive or inductive reasoning, have a peek here.

Images courtesy of Wikipedia.