I’d planned this word for Burn’s Night, the January 25th celebration of Scotland’s national Bard. Like Galoot, I figured the word to be of Scots origin, but as with Galoot, the etymology of hootenanny proves unusual. I’m now calling it an American neologism of the year 1900 or so.

I’d planned this word for Burn’s Night, the January 25th celebration of Scotland’s national Bard. Like Galoot, I figured the word to be of Scots origin, but as with Galoot, the etymology of hootenanny proves unusual. I’m now calling it an American neologism of the year 1900 or so.

My erroneous thinking can be traced to by a couple of fine nights of drinking pints and listening to music at a pub of that name in Inverness. It’s a fine venue for “trad” or modern music and the crowd is friendly. In any case, our word seems American in origin. At Etymology Online, we find either an informal gathering of folk musicians, as compared to any old jam session, or (new to me) a type of tool used by car-thieves in the early 1930s. The OED gives it a first use of 1906, in a similar sense of “thingumajig,” “doo-dad,” or “whatchamacallit.”

In any case, in Inverness I attended a hootenanny, since we had lots of locals come by to play traditional tunes. There’s a long tradition at work here; across sea in Ireland, we’d call that a céilí; in Scots’ Gaelic, it’s cèilidh. I hope you encounter one in your lifetime; travel to small places in the Celtic lands, as we like to do–no packaged tours!–and you’ll find them. They can include poetry and dance, too. The most haunting for me? An old man singing a traditional ballad a capella in the back room of a tiny pub on the island of Inishmore, a couple of years back. It brought a bunch of young toughs who were with him to respectful silence. We all raised our glasses when the singer finished to toast the gentleman, and the whisky and stout ran like a river afterwards while a band played popular tunes.

As for this side of the Atlantic, I’m too young to recall the TV show for folk performers that ran briefly in the early 60s. The network would not allow Pete Seeger to perform unless he signed what amounted to a loyalty oath to the US, a late-blooming weed from McCarthy’s witch-hunts of a decade earlier. Seeger refused, and others boycotted the show. It’s a distant prelude to the Kennedy Center fiasco currently underway.

Set aside today’s rancor and enjoy some locally sourced live music soon. It might not be a hootenanny, but you’ll be continuing an old tradition. As for our word? I was planning to place it with “shindig” in our list of endangered words. When did you last hear either?

Wrong, again, Mister Blogger. There’s a revival for our word since 2000. The frequency chart at the OED shows a steady rise in usage until 1990, then a dip and recovery. I am pleased to report that are back to peak hootenanny. Is a might wind a-blowin’ again for folk music?

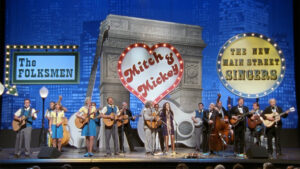

If you have seen Christopher Guest’s film, you’ll get the reference. My musical tastes run more to glam, Americana, Brit Pop, Celtic (Trad or modern), and post-punk than to 1950s-60s American folk, but this film is a must-see for its humor and one big, endearing hootenanny. Send words, folk songs, and metaphors my way by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below. Want to write a guest entry? Let me know!

Send words, folk songs, and metaphors my way by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below. Want to write a guest entry? Let me know!

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Image: Wikipedia page for that long-gone TV show