Science-Fiction and Fantasy writer Fran Wilde, who works with my students when she’s on campus, once quipped “Joe, you are a misanthrope in danger of becoming a curmudgeon.”

Science-Fiction and Fantasy writer Fran Wilde, who works with my students when she’s on campus, once quipped “Joe, you are a misanthrope in danger of becoming a curmudgeon.”

Fran actually had that backwards, and that says a great deal about how fine a line exists between these words and, perhaps, who they represent. The Oxford English Dictionary Online only takes the term back to the 16th Century, in the sense of being mean-spirited and mistrustful. The word’s genesis, the OED notes, is unknown.

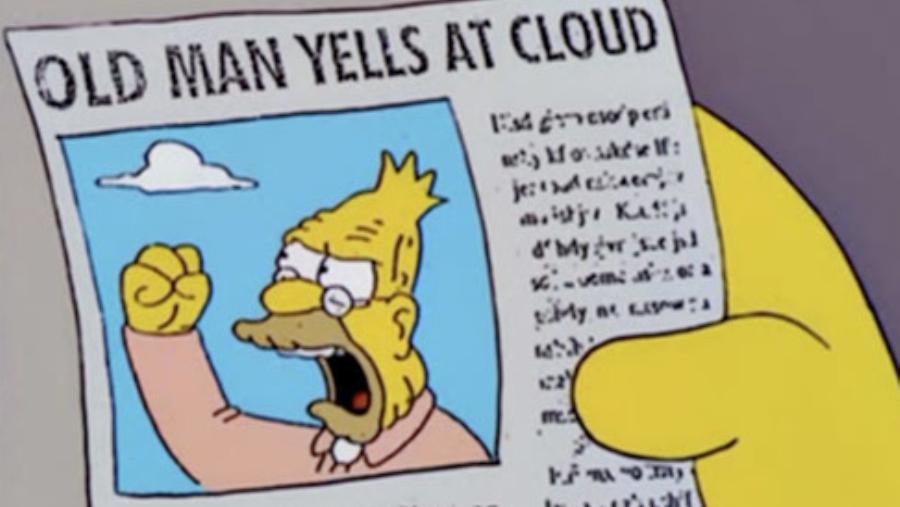

Like some curmudgeons I have known, then, our word seems to have just shown up to spoil our days. The American Heritage Dictionary also reveals that for two centuries, attempts to find the origin of the word have failed. The term has, moreover, shifted in what it signifies. For a long time, the elusive curmudgeon often was depicted as old, mean, and miserly. Think of Ebeneezer Scrooge (a character I portrayed in our 6th Grade Christmas play). Lately the grasping miser seems to have given way to a merely grumpy old geezer, usually male. Thus my Simpsons’ example.

So short-tempered, mistrustful, grumpy? That’s me, Fran. But a hater of all mankind? Nonsense! That would be someone like Mark Twain late in his life, who wrote in an 1898 notebook entry that “The human race consists of the damned and the ought-to-be damned.” Those are the words of someone who really hates the entire species: a misanthrope. You see it in his later work, especially after A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.

I hope my fate is gentler than the hero of that novel or, for that matter, its author. Writing this has me grinning, something curmudgeons rarely do. So perhaps there is hope. Just stay off my lawn this summer!

This blog will continue through the balmy months, so nominate a word by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Words of the Week here.