I love few places on Earth more than the Shenandoah Valley. Richmond’s West-of-The-Boulevard neighborhood comes close, as do parts of Western Ireland and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Segovia Spain, and not least, the Fundy Coast of Nova Scotia. I would gladly live the rest of my days in any of them and never look back.

I love few places on Earth more than the Shenandoah Valley. Richmond’s West-of-The-Boulevard neighborhood comes close, as do parts of Western Ireland and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Segovia Spain, and not least, the Fundy Coast of Nova Scotia. I would gladly live the rest of my days in any of them and never look back.

In fact, I’m hoping to spend the hot months of my retirement years in the first one: the trick involves finding the right rural property in The Valley. I like neighbors fine, but I don’t want to see them except when I wave my hat at them from the tractor’s seat as they go down the road. Unless I were to live in Segovia or West of Richmond’s Boulevard, I don’t even want to see other houses. Having managed rural land for decades, I know what we’ll face.

All of this serves as an introduction to our Word of the Week and a personal story. I learned our from Atlantic columnist Arthur Brooks, who switched from being a Washington Think-Tank wonk to a writer about happiness. I heartily approve of his change of career. I used to cringe at his columns; now I seek them out. Brooks writes, in a 2021 piece “Find the Place You Love. Then Move There,” about choosing where to choose to live:

There is a word for love of a place: topophilia, popularized by the geographer Yi-Fu Tuan in 1974 as all of “the human being’s affective ties with the material environment.” In other words, it is the warm feelings you get from a place. It is a vivid, emotional, and personal experience, and it leads to unexplainable affections.

He acknowledges that we don’t all have the luxury of choice, though moving across town can change your life. In terms of origins, Wikipedia’s page on the subject provides a solid etymology. Alan Watts reports, in his autobiography, that poet John Betjeman coined the term, and W.H. Auden wrote in his introduction to a volume of Betjeman’s poetry that history with a landscape results in topophilia.

Appropriately, my topophilic relationship with the Valley goes way back. I recall trips with my parents to buy apples in many places, as my dad was a trucker, then a produce wholesaler. Best of all involved visiting friends at the little hamlet of Massie’s Mill, VA, where Tom Massie managed an orchard. Tom was a business associate second and friend first to my dad. Dad saw Tom as a practical Appalachian farmer whose strong, quiet persona, long history in that place, and obvious love of the land made him special. Even pre-teen me picked up on this feeling. He adored that farm and it showed in his care for it.

Topophilia swayed my old man, who was a tough city-boy through and through, but he’d mellow the second he stepped out of his big GM car at Tom’s.

The Massie family lost their matriarch in the terrible floods of 1969, when the remnants of Hurricane Camille parked themselves over that part of the Valley. Tom’s mother’s house was washed away to the foundation and her body never recovered. My dad barely escaped earlier in the day. He was hauling a load of apples to Winchester in ferocious weather down the Tye River Valley. He said the rain was solid and the road treacherous. He knew something awful was coming so he kept going as water covered the road. He spoke quietly later of the Massie’s tragedy, but when we returned, Tom and his family seemed as tied to that beautiful place as ever.

My own topophilia for The Valley continued to deepen over the years. Decades later, my wife and I began to make monthly trips to a farm near Stuart’s Draft, VA, to buy feed for our growing flock of chickens. With the flock approaching 90 hens, we go through more than 300 lb of feed monthly. Ostensibly, the trip lets us save money by buying truckloads in bulk, but the trip also reinforces my topophilia.

I have a theory (run while you can). If we really loved the places we lived, and I don’t mean the structures that shelter us, would we ruin them with sprawl, pollution, wider roads, and other forms of debasement? Rural Henrico was once lovely. No more. So many places I visit around Richmond’s periphery have become generic, forgettable. Money and convenience drive our decisions, not topophilia. Maybe too many of us don’t stay in a place long enough to establish that deep connection.

If we practiced topophilia by living where we love, wouldn’t we do a better job? Sadly, there’s no guarantee. There’s an Amazon distribution center a few miles up the rural road from where we buy our feed. The jobs are nice and yes, I have a Prime account. Yet if we loved places more, we’d build such giant buildings on gray-field sites where a closed factory now stands.

The Pandemic afforded us the opportunity to rethink how we work and where we live. It promoted me, in part, to retire from full-time work early. The Valley, after all, awaits. I’m laying my plans.

What places do you love most? Why can’t you move there? As Brooks notes, “perhaps the biggest barrier for you is the sheer audacity of moving for a feeling. The reward from moving just because you want to is hard to defend logically. Some people will think you are crazy.”

My old man was a homebody. He’d have thought me crazy for living on a Goochland farm, but crazier still for my topophilic need for mountain vistas and even more farmwork.

Sorry, Pop. I’ll plant some apple trees, just like Tom Massie did.

Send words and metaphors my way by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

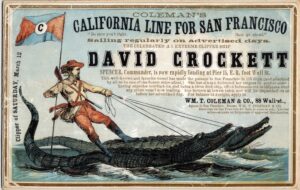

image source: location undisclosed. I don’t want neighbors I can see…

We’ve another loan-word from Latin this week, meaning to have foresight. That power need not be supernatural, but simply the art of seeing ahead often attributed variously to meteorologists, economists, futurists, gamblers, and soon-to-be-lost drivers who overrely on map apps.

We’ve another loan-word from Latin this week, meaning to have foresight. That power need not be supernatural, but simply the art of seeing ahead often attributed variously to meteorologists, economists, futurists, gamblers, and soon-to-be-lost drivers who overrely on map apps.