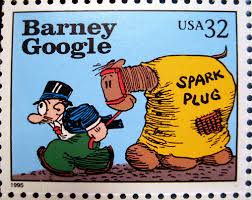

Being an academic includes, believe it or not, a measure of humility. So when I covered this term here before, I wrote “my money, as well as Wikipedia’s, is on Barney Google, a nearly forgotten cartoon character. ”

I may have lost that bet. There’s some evidence that Barney’s popularity led to a shift in an existing term.

While doing some research on sites to visit in Northumbria, in service of a long-term plan to walk the Hadrian’s Wall Path, I came across the legend of The Lambton Worm, a crawling horror dispatched by local nobleman, Sir John Lambton. As a lad he went fishing and caught the creature, when it too was a youngster. He disposed of the strange “fish” by tossing it in a well, and trouble followed. You may recall the legend if you saw Ken Russell’s B-movie adaptation of Bram Stoker’s reportedly awful novel, The Lair of the White Worm.

I hope to visit the scene of these adventures, south of Newcastle, when I begin my rambles across the north of England. As for my evidence that I was wrong earlier about googly eyes? Doubts began when I found a folk-song composed in 1867 by Clarence M. Leumane, and I’ll quote part of it here, after Sir John unwisely tosses the baby worm down a well:

But the worm got fat an’ grewed an’ grewed,

An’ grewed an aaful size;

He’d greet big teeth, a greet big gob,

An greet big goggly eyes.

The Online Etymology Dictionary notes that our “googly eyes” comes from the older “goggly eyes” of the song, and, further back, to the 1530s and Middle English.

Sorry Barney Google, our term is far older than you. Perhaps Barney’s pop-eyed look helped morph “goggly-eyes” to “googly-eyes”?

Send words, stick-on googly eyes, monster legends, and metaphors my way by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below. Want to write a guest entry? Let me know!

Send words, stick-on googly eyes, monster legends, and metaphors my way by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below. Want to write a guest entry? Let me know!

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

Images: Picpik.com and Wikipedia.