Our word came to me spelled “autarky,” but then I discovered a second spelling, “autarchy.” The OED reveals a curious double-meaning, both related to our current economic moment in the United States and perhaps, around the world.

Our word came to me spelled “autarky,” but then I discovered a second spelling, “autarchy.” The OED reveals a curious double-meaning, both related to our current economic moment in the United States and perhaps, around the world.

First, autarchy can mean policies that promote “economic self-sufficiency in a political unit,” but second and more darkly, “despotism.” Both ideas clearly have been tossed about by supporters and opponents of current tariffs on foreign goods. This blog is not interested in advocacy; feel free to ask my opinion of tariffs, in person. You’ve been warned.

For this blog, however, I do find that the double-meaning needs a bit of unpacking. Why would self-sufficiency and tyranny share one word? Both meanings come from the Greek αὐτάρκεια, so we have a loan word that caught on in the 1600s. Both senses of our word first appeared in print then with an example meaning “absolute sovereignty, despotism” cropping up in 1665. Earlier, in 1617, we get “The Autarchie and selfe-sufficiencie of God” but here it’s God’s self-sufficiency and not supreme power being evoked.

Autarky in its dark sense was often used in the 1930s to describe the enemies of world trade, then Imperial Japan’s drive for a “Greater East-Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere” and, as you’d expect, European Fascism.

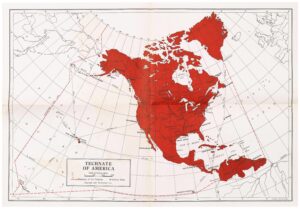

In the US, the America-First platform after World War 1 and the rise of Technocracy, Inc. in the 30s both included autarchy in both senses of the word, with the latter wanting to build a continental “Technate” from the North Pole to beyond Panama as an “independent, self-sustaining geographical unit.” We heard this idea again recently and I looked up the old maps of the planned Technate. One appears at the top of this post. Make of its influence what you will.

When I studied Technocracy as part of my doctoral dissertation in the early 1990s, the idea seemed quaint, even ridiculously antique. Since then the frequency of usage for our word remained nearly steady, peaking in 2000.

Will ours be a Century of Autarchy / Autarky? We’ll find out.

Send words and metaphors my way by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Metaphors of the Month here and Words of the Week here.

image: 1930s map of the Technate, from Technocracy Inc.

I love this word. I love the idea that New Orleans named a newspaper after it. There’s a Mississippi town called Picayune that I should visit, and of course I love it that Mark Twain / Sam Clemens used the word and has also been skewered with it. In this recent example in The Atlantic by Graeme Wood, he describes a new biography focusing on Clemens’ difficult personal life and financial disasters thus: “His credulity led to misadventures the details of which are so picayune that Chernow’s emphasis on them can be maddening.” No detail about Clemens’ life can be maddening to me: I immediately ordered a copy of Chernow’s giant biography, Mark Twain.

I love this word. I love the idea that New Orleans named a newspaper after it. There’s a Mississippi town called Picayune that I should visit, and of course I love it that Mark Twain / Sam Clemens used the word and has also been skewered with it. In this recent example in The Atlantic by Graeme Wood, he describes a new biography focusing on Clemens’ difficult personal life and financial disasters thus: “His credulity led to misadventures the details of which are so picayune that Chernow’s emphasis on them can be maddening.” No detail about Clemens’ life can be maddening to me: I immediately ordered a copy of Chernow’s giant biography, Mark Twain.