This word seems easy enough. The adjective refers to existence. That is, indeed, the earliest definition in The OED Online, “of or relating to the existence of a thing.” That sense goes back as far as the 17th Century.

This word seems easy enough. The adjective refers to existence. That is, indeed, the earliest definition in The OED Online, “of or relating to the existence of a thing.” That sense goes back as far as the 17th Century.

Outside of academia, one often encounters the word in the sense of “being a matter of life or death.” I’ve heard North Korean nuclear weapons, unmarked asteroids hurtling by the Earth, and slowly mounting climate change all referred to as “existential threats” to human civilization or even the survival of our species.

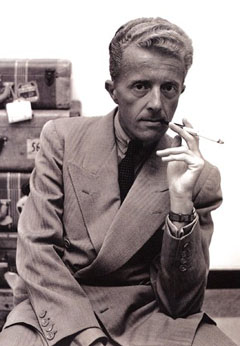

If only, however, it were that stark. We would have a very short post indeed this week, but we can blame mid-20th-Century philosophers and writers for making matters existential so complex. Here the OED and other references take us into the realm of existential philosophy, or existentialism. If you have read the works of Sartre or Camus, you may consider it a gloomy school of thought. Read The Stranger, or any of American author Paul Bowles’ austere and beautiful fiction to encounter the core of existentialism: that humans are alone in an indifferent if not hostile universe. Our actions, while freely chosen on our parts, mean, finally, nothing.

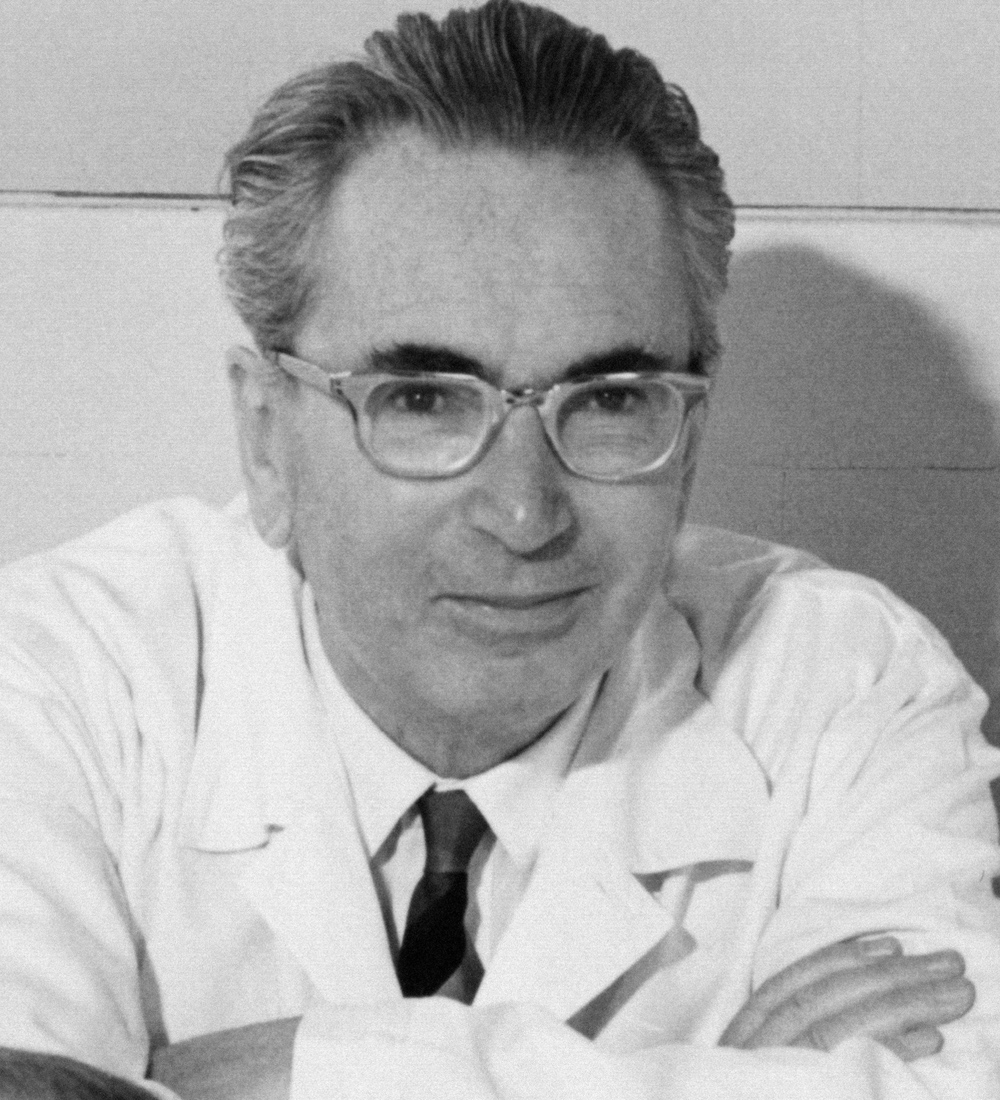

Yet an existentialist philosophy need not be so bleak. I’ve been reading Man’s Search For Meaning by Viktor Frankl, after running across the work as a reference in an article about the value of failure in learning.

Frankl, an Austrian psychologist, not only survived Auschwitz and, almost as harrowing, a Bavarian concentration camp in the Second World War’s last months, but he practiced medicine in the latter camp. He had little to offer fellow prisoners aside from a few aspirin doled out by the SS and kind words. Despite contracting typhus, Frankl reconstructed a manuscript seized from him at Auschwitz. It contained a new system of psychology that Frankl called logotherapy. This was an existentialist form of therapy to address what the psychologist called “the existential vacuum” of modern life, where cultural traditions have waned and leisure time often results in mere boredom. Frankl’s theory and practice emphasize focusing on creating meaning in one’s life and pursuing goals, even in the bleakest situations.

That’s hardly gloomy, yet there too our word of the week speaks to the essentials of human existence.

This blog will continue all summer, so nominate a word by e-mailing me (jessid -at- richmond -dot- edu) or leaving a comment below.

See all of our Words of the Week here.

Images of Viktor Frankl, by Prof. Dr. Franz Vesely, and of Paul Bowles courtesy of Wikipedia.