In case you don’t know, there’s a total eclipse coming to North America next year, on August 21 to be precise. You can find lots of information about it by Googling, naturally.

You’ll only be able to see a total eclipse along a certain path through the US. I wanted to know where on the path I should go. In particular, where is the weather most likely to be clear on that day?

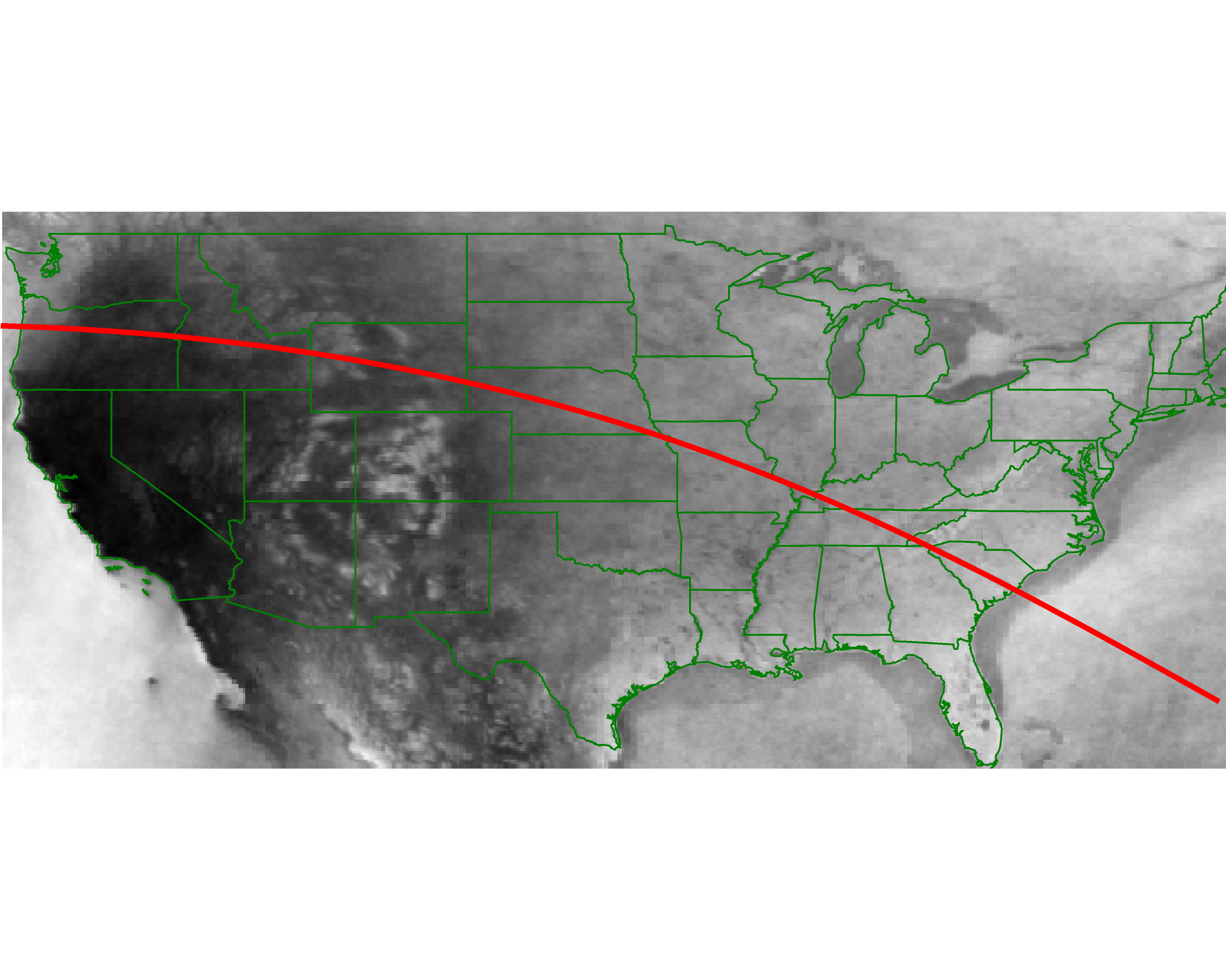

I asked my brother, who’s a climate scientist, where to go to find this out. He pointed me to the cloud fraction data from NASA’s MODIS TERRA/AQUA sensor, which contains whole-earth cloud cover maps. Here’s the answer:

The red curve is the middle of the path of totality of the eclipse. The eclipse will be total over a band of maybe 30-50 miles on either side. The colors show average cloud cover. Black is good and white is bad.

(In case you’re dying to know the details, here they are. I grabbed the data for the past 10 years for the time around August 21. The most sensible data product to use seems to be the 8-day averages. August 21 is right on the edge of one of those 8-day windows, so I took the two eight-day windows on either side, and averaged together those 20 maps.)

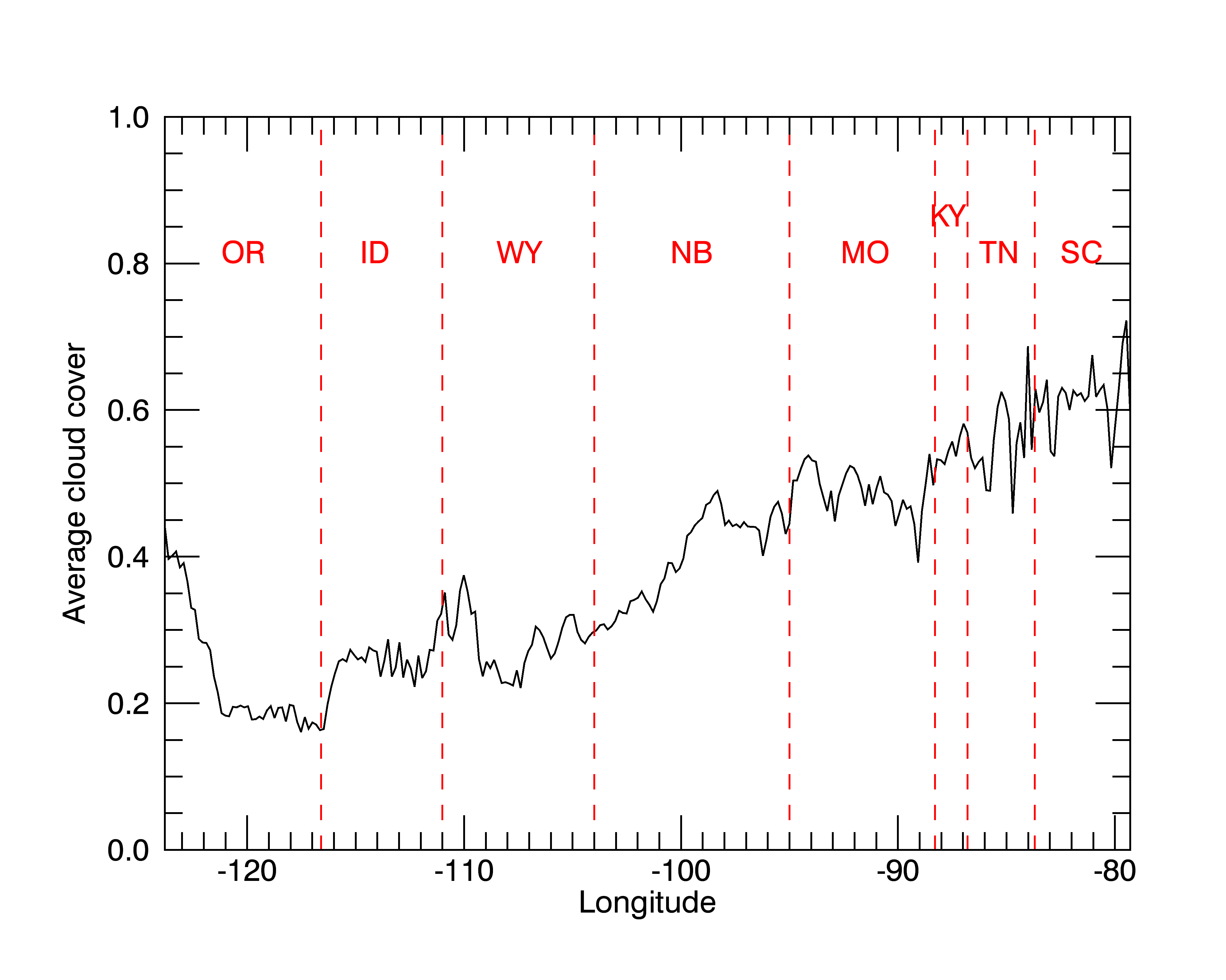

Here’s another way to look at it: a graph of average cloud cover along the path of totality, across the US. The red dashed lines show state boundaries. The path clips little corners of Kansas, Illinois, and North Carolina, which I didn’t bother to mark.

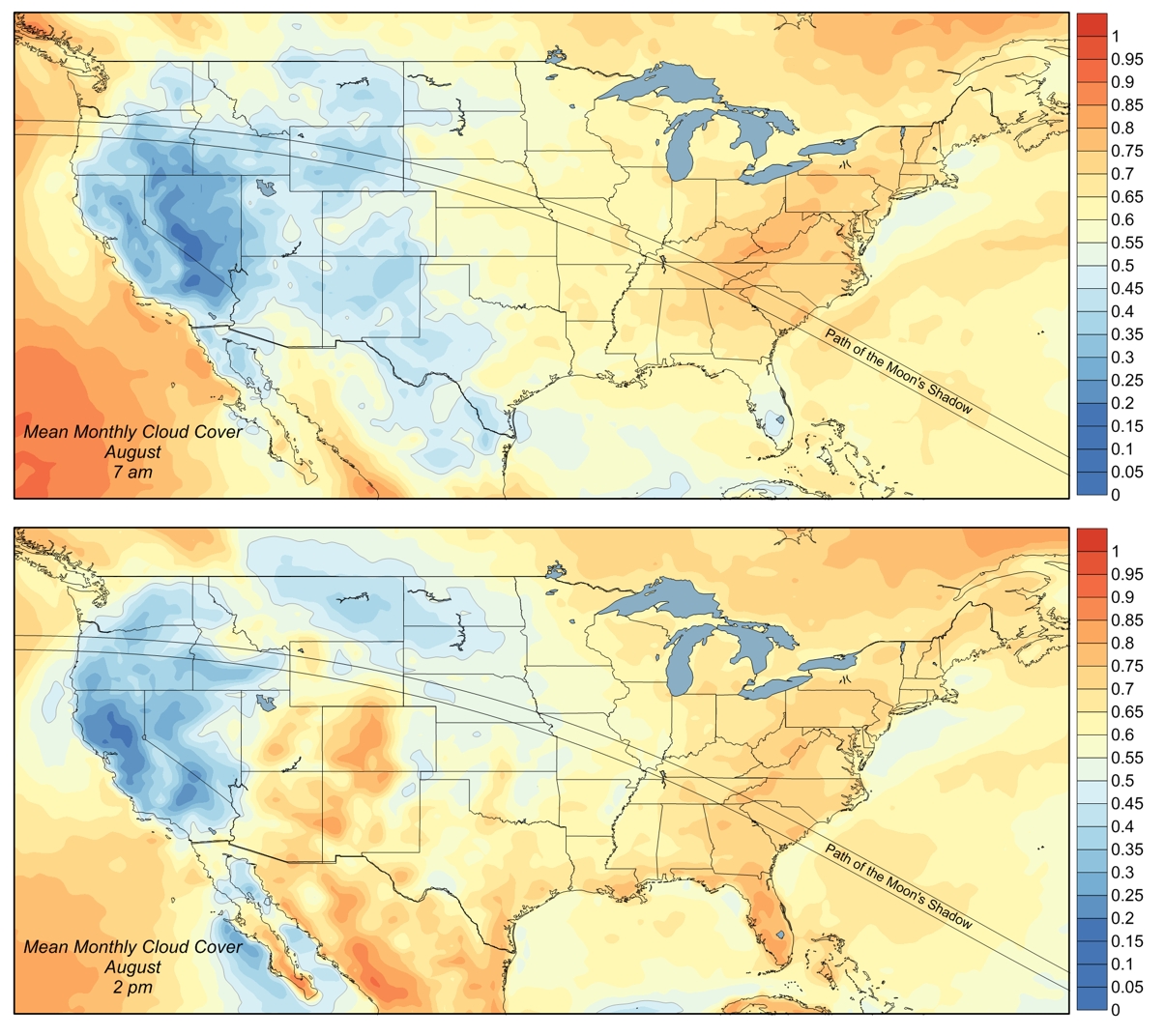

After making my map, I found this one, which reaches similar conclusions.

Hotel rooms along the path of totality are already hard to find. Make your plans right away!

Ted, I also liked the web site http://eclipsophile.com/overview/ (which might be where you got your last figure from) — especially figure 4, which gives some extra information, which might help figure out more precisely where things are.

Might I also plug this? https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=fr.free.kmganga.SolarEclipse2 ?

This app looks great! I didn’t know about it.

Yes, that figure is from eclipsophile. There is a link to the page above the figure, but maybe it wasn’t clear that “this one” in that sentence refers to that figure.

The figure you refer to uses more data than I did — 200 years instead of 20. I’m not sure whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing: more data is better, but weather is not statistically stationary (there’s climate change, after all). Probably the best thing to do is to take the 200 years of data and fit a line to cloud cover as a function of time at each location. But I’ve already made my plans to go to Oregon, and besides that sounds like work.

Splitting the data between morning and afternoon is a good idea. At least out West, the eclipse is in the morning.

I see that that figure is by someone named Jay Anderson. I bet it’s the Jay Anderson I went to grad school with. I had no idea what he was up to.

I have been thinking about going to see the eclipse for ages, but am still undecided. If I do go, I’d probably go to St. Louis or Nashville or something like that — more hotel rooms, hopefully, and with a bit of planning I might be able to avoid traffic hassles. I thought hard about doing the western Oregon visit, but in the end it’s a long-enough trip that I want to have something else to do in case it gets clouded out. Or even if it doesn’t, really. Even if it is more likely to get clouded out further east.

Another possibility that I haven’t checked out must was around the Grand Tetons.

I’ve never been to Portland, and there are people in the area I’d like to see. Plus my brother and his family will be coming down from Washington. So there are lots of reasons besides weather that Oregon works for me. In your shoes, the calculation would be quite different.

I’d be willing to bet that lodging around the Grand Tetons at eclipse time will be hard to find.