People sometimes ask me whether, as a scientist, I get annoyed by scientific inaccuracies in movies. Sometimes, I guess, but not usually. In science fiction, I think it’s fine if the fictional world you’ve created breaks the rules of our actual universe, as long as it consistently follows its own rules.

I actually find linguistic inaccuracies in historical fiction more annoying than scientific inaccuracies in science fiction. For some reason, linguistic anachronisms raise my nerd hackles.

I was thinking about this recently because, as a middle-aged Prius-driving NPR listener, I am legally obliged to watch Downton Abbey.

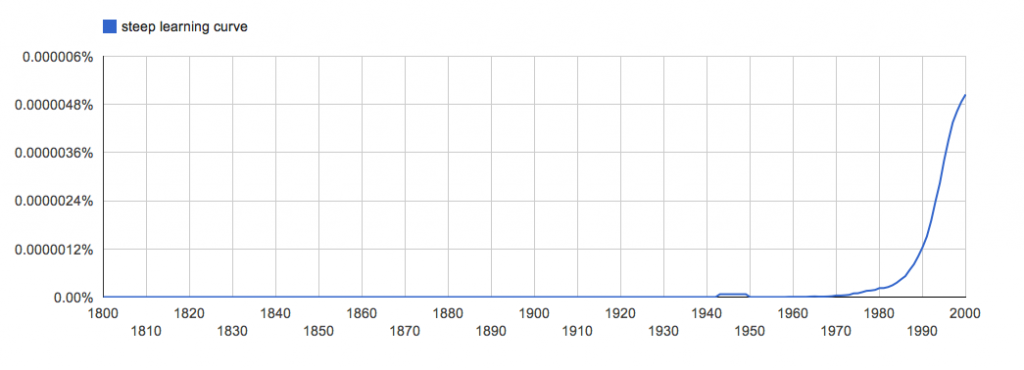

Twice during the current season, characters have described themselves as being “on a learning curve,” in one case “on a steep learning curve.” This phrase is irritating enough in contemporary parlance, but in the mouths of 1920s characters it’s all the more grating.

I posted a gripe about it on Facebook, with some actual data from the awesome Google Ngram viewer:

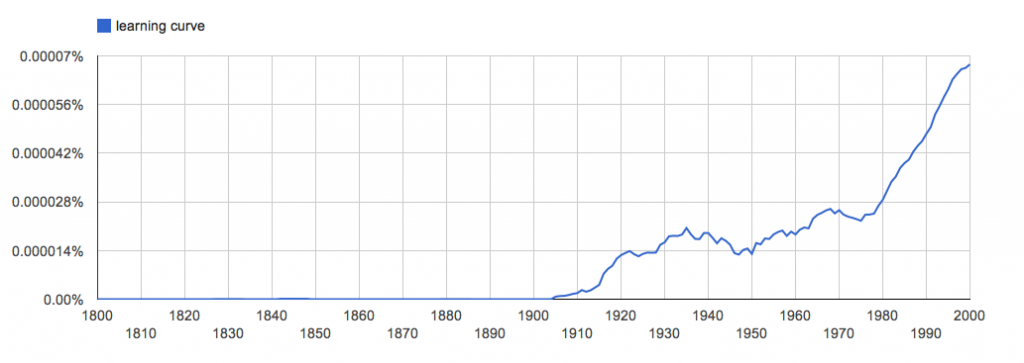

A friend made the fair observation that “learning curve” goes back further than “steep learning curve”:

If Matthew Crawley and Tom Branson were linguistic trendsetters, maybe they could have been saying this in the 1920s, but I’m not buying it, and Ngram will help me justify my skepticism. I knew Ngram had an amazingly huge corpus of searchable books, but it turns out to be more powerful and flexible than I’d realized.

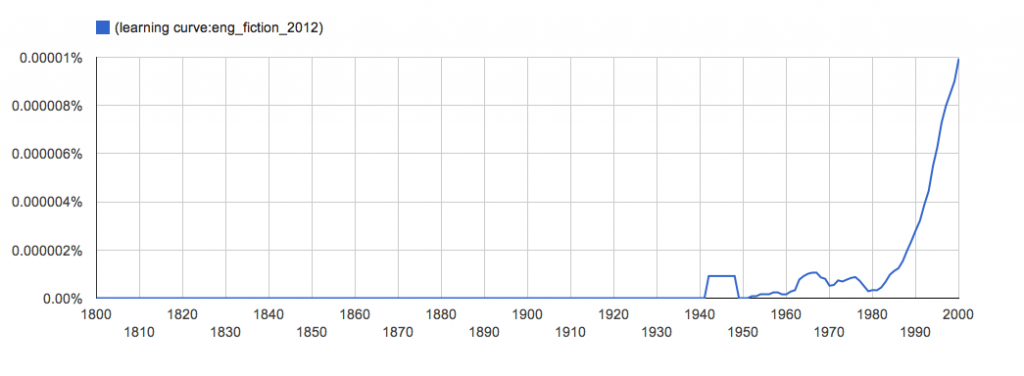

I suspect that the term was only used in a technical context, to describe actual graphs of learning, until much, much later. The citations of the phrase in the OED are consistent with this, but there are only a couple of them, so that’s not much evidence. Ngram can help with this: we can look at the phrase’s popularity in just fiction, rather than in all books.

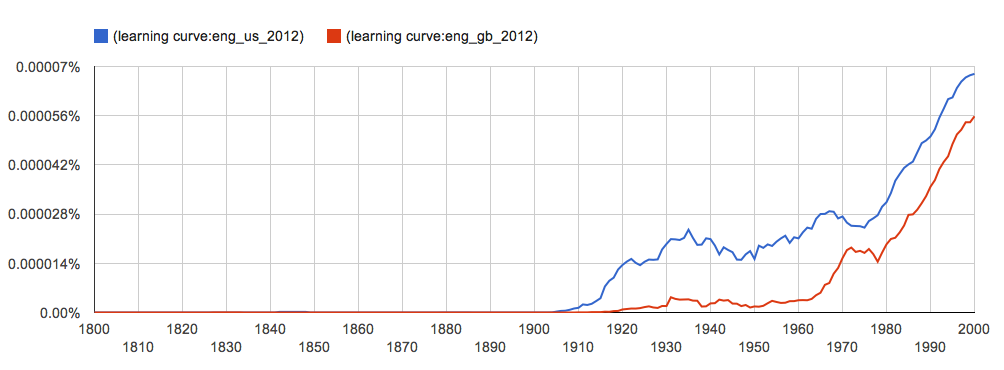

The phrase takes off in fiction in the last couple of decades, around when (I claim) people actually started saying it in non-technical contexts. Also, in the early years, it was almost entirely an American phrase:

(That’s all books, not just fiction.)

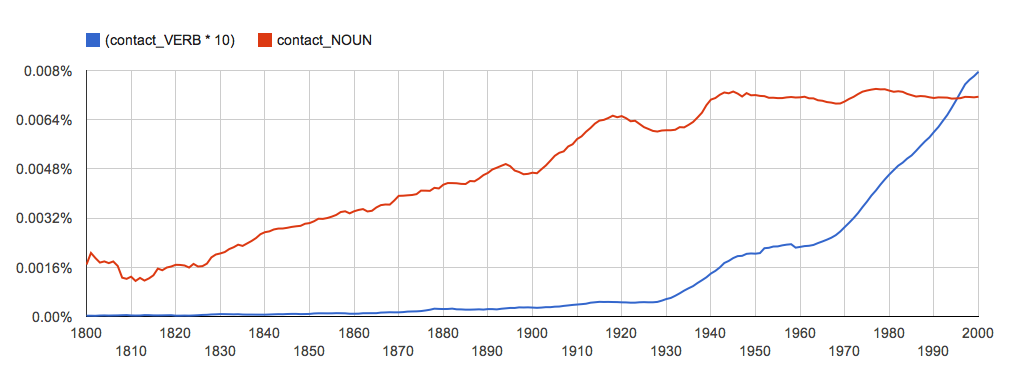

Another Downton linguistic anachronism: “contact” as a verb. I’d originally searched Ngram for “contacted” to illustrate this, but it turns out that you can tell it to search for words used as particular parts of speech. Here’s “contact” as both verb and noun:

(Verb in blue, amplified by a factor of 10 for ease of viewing.)

The fact that you can do this strikes me as quite impressive technically. Not only have they scanned in all these books and converted them to searchable text, but they’ve parsed the sentences to identify all the parts of speech. That’s a nontrivial undertaking. As Groucho Marx apparently never said, “Time flies like an arrow; fruit flies like a banana.”

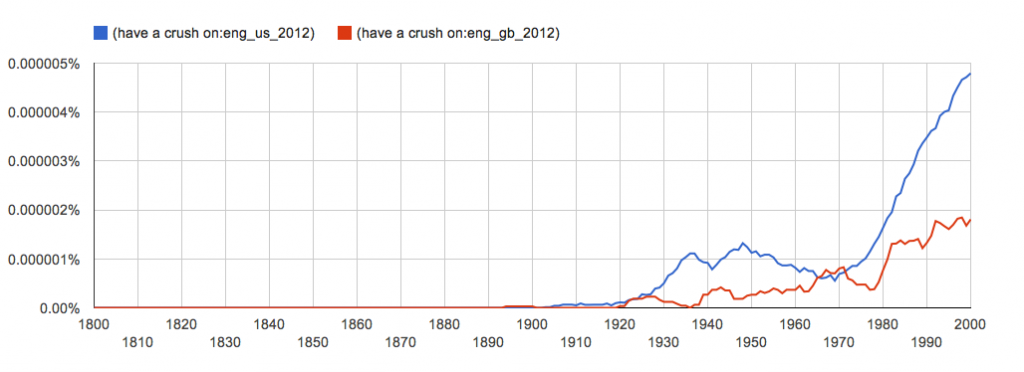

The phrase “have a crush on” also came up and sounded off to me, but I was pretty much wrong on that. It was starting to become common in the 1920s, although it was mostly American:

In hindsight, I should have known that: the Gershwin song “I’ve got a crush on you” dates from a bit later than Downton, but not that much.

“contact” as a verb

Reminds me of a recent exchange over at the e-astronomer (paraphrased):

A: I contracted at company XY

B: I hope you’ve now returned to normal size

What about people in the 1920s referring to World War I?

What do you think about period pieces from earlier? Anything before, say, the 15th century would be incomprehensible to modern viewers. Since it is translated anyway, is it OK to use the latest gangsta slang or whatever?

What about things set in historical periods in non-English-speaking countries? Most US films tend to give the characters a (modern) British accent (Kevin Costner in Robin Hood being an exception).

What about something like Shadow of the Vampire? (Wonderful film, by the way.) The film is in English, but takes place in 1920s Germany, so the characters (played by actors whose first language is English) have a German-sounding accent.

The general rule seems to me to be that you should adopt a convention and stick to it. Because the language in Downton Abbey generally seems to be appropriate to the period, the moments when it’s not are jarring. But I don’t object to Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar being in English rather than Latin, because that convention is followed consistently (except for the one line “et tu Brute”).

The use of accents to signify foreign characters is a common enough convention that Mel Brooks made fun of it in History of the World Part 1: Cloris Leachman, playing a peasant in the pre-revolutionary France, says something like, “We’re so poor that we don’t even have a language — just an accent!”

Also, Brooks’s To Be Or Not To Be, which is set in Poland, starts off with all the dialogue in Polish, until an announcer says, “Ladies and Gentlemen: In the interest of clarity and sanity, the rest of this movie will not be in Polish.” The rest of the dialogue is in English.