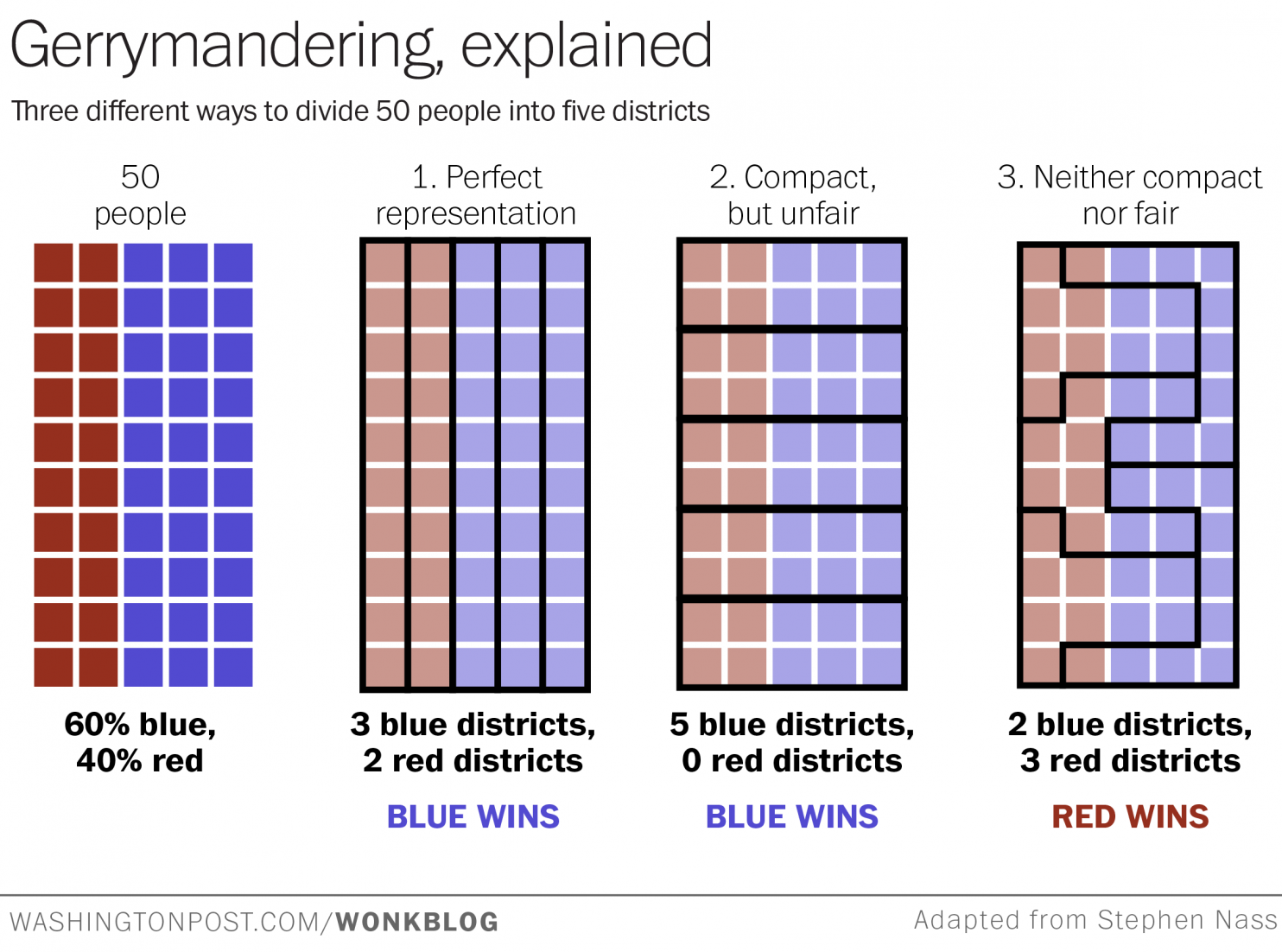

The Washington Post has a nice graphic explaining how gerrymandering works.

If the people drawing the district lines prefer one party, they can draw the lines as on the right: they pack as many opponents as possible into a few districts, so that those opponents win those districts in huge landslides. Then they spread out their people to win the other districts by slight majorities.

The solution people generally propose is to put the district-drawing power into the hands of non-partisan people or groups. While I think this is certainly a good idea, it’s worth mentioning that you can get “unfair” results even without deliberate gerrymandering. In particular, if members of the political parties happen to cluster in different ways, then even a nonpartisan system of drawing districts can lead to one party being overrepresented.

I don’t propose to dig into the details of this as it affects US politics. Briefly, the US House of Representatives is more Republican than it “should” be: the fraction of representatives who are Republican is more than the nationwide fraction of votes for republicans in House races. Similar statements are true for various states’ US House delegations and for state legislatures, sometimes favoring the Democrats. No doubt you can find a lot more about this if you dig around a bit. Instead, I just want to illustrate with a made-up example how you can get gerrymandering-like results even if no one is deliberately gerrymandering.

To forestall any misunderstanding, let me be 100% clear: I am not saying that there is no deliberate gerrymandering in US politics. I am saying that it need not be the whole explanation, and that even if we implemented a nonpartisan redistricting system, some disparity could remain.

I should also add that nothing I’m going to say is original to me. On the contrary, people who think about this stuff have known about it forever. But a lot of my politically-aware friends, who know all about deliberate gerrymandering, haven’t thought about the ways that “automatic gerrymandering” can happen.

Imagine a country called Squareland, whose population is distributed evenly throughout a square area. Half the population are Whigs, and half are Mugwumps. As it happens, the two political parties are unevenly distributed, with more Whigs in some areas and more Mugwumps in others:

The bluer a region is, the more Whigs live there. But remember, each region has the same total number of people, and the total number of Whigs and Mugwumps nationwide are the same.

You ask a nonpartisan group to divide this region up into 400 Congressional districts. They’re not trying to help one party or another, so they decide to go for simple, compact districts:

Each district has an election and comes out either Whig or Mugwump, depending on who has a majority in the local population. In this particular example, you get 197 Mugwumps and 203 Whigs. pretty good.

Now suppose that the people are distributed differently:

Note that the blue regions are much more compact. There’s lots of dull red area, which is majority-Mugwump, but no bright red extreme Mugwump majorities. The blue regions, on the other hand, are extreme. The result is that there’s a lot more red area than blue, even though there are equal numbers of red folks and blue folks.

Use the same districts:

This time, the Mugwumps win 245 seats, and the Whigs get only 155. Nobody deliberately drew district lines to disenfranchise the Whigs, but it happened anyway. And the reason it happened is very similar to what you’d get with deliberate gerrymandering: the Whigs got concentrated into a small number of districts with big majorities.

Once again, I’m not saying that this is what’s happened in the US House of Representatives. On the contrary, the evidence of deliberate gerrymandering is very strong, and given the incentives, it would be quite surprising if it did not occur. But if members of one party tend to “clump” more strongly than members of the other party, then this sort of effect can certainly occur, and could form a part of the discrepancy we see.