Christie Aschwanden has a piece on fivethirtyeight.com about the supposed “crisis” in science. She writes about recent high-profile results that turned out to be wrong, flaws in peer review, and bad statistics in published papers.

By far the best part of the article is the applet that lets you engage in your own p-hacking. It’s a great way to illustrate what p-hacking is and why it’s a problem. The idea is to take a bunch of data on performance of the US economy over time, and examine whether it has done better under Democrats or Republicans. There are multiple different measures of the economy one might choose to focus on, and multiple ways one might quantify levels of Democratic or Republican power. The applet lets you make different choices and determines whether there’s a statistically significant effect. By fiddling around for a few minutes, you can easily get a “significant” result in either direction.

Go and play around with it for a few minutes.

The rest of the article has some valuable observations, but it’s a bit of a hodgepodge. Curmudgeon that I am, I have to complain about a couple of things.

Here’s a longish quote from the article:

P-hacking is generally thought of as cheating, but what if we made it compulsory instead? If the purpose of studies is to push the frontiers of knowledge, then perhaps playing around with different methods shouldn’t be thought of as a dirty trick, but encouraged as a way of exploring boundaries. A recent project spearheaded by Brian Nosek, a founder of the nonprofit Center for Open Science, offered a clever way to do this.

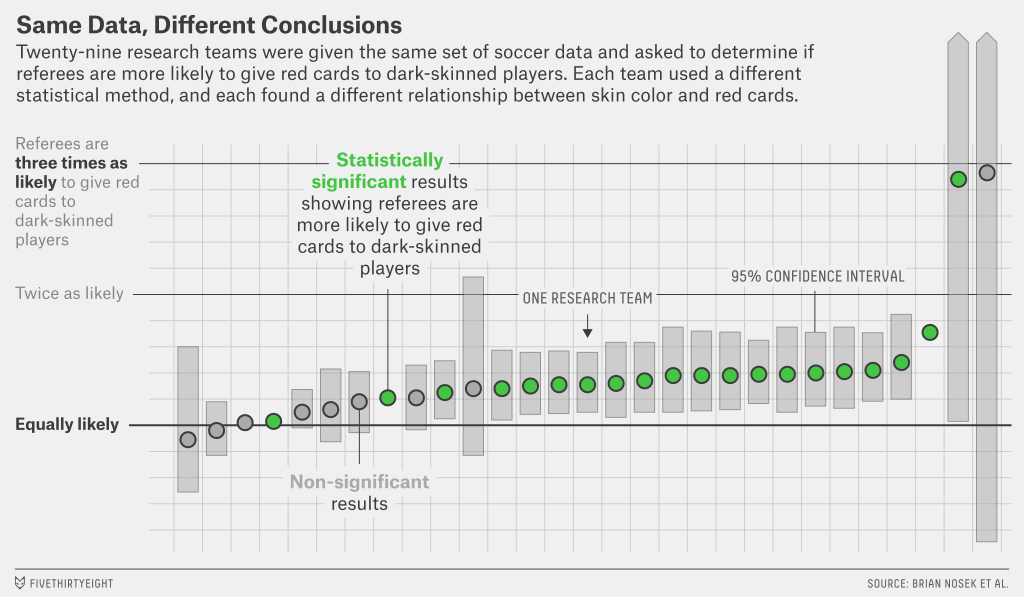

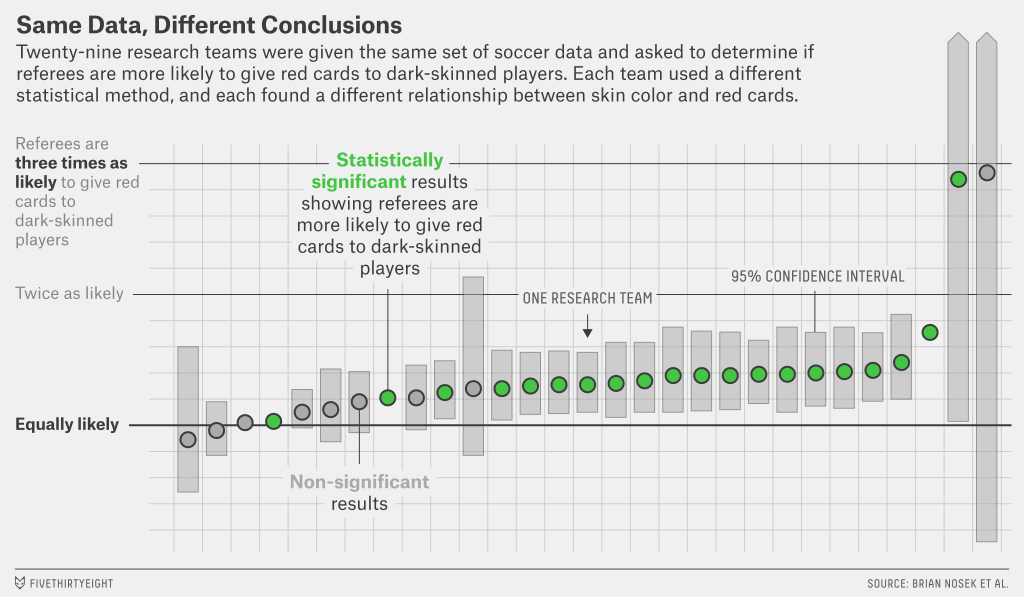

Nosek’s team invited researchers to take part in a crowdsourcing data analysis project. The setup was simple. Participants were all given the same data set and prompt: Do soccer referees give more red cards to dark-skinned players than light-skinned ones? They were then asked to submit their analytical approach for feedback from other teams before diving into the analysis.

Twenty-nine teams with a total of 61 analysts took part. The researchers used a wide variety of methods, ranging — for those of you interested in the methodological gore — from simple linear regression techniques to complex multilevel regressions and Bayesian approaches. They also made different decisions about which secondary variables to use in their analyses.

Despite analyzing the same data, the researchers got a variety of results. Twenty teams concluded that soccer referees gave more red cards to dark-skinned players, and nine teams found no significant relationship between skin color and red cards.

The variability in results wasn’t due to fraud or sloppy work. These were highly competent analysts who were motivated to find the truth, said Eric Luis Uhlmann, a psychologist at the Insead business school in Singapore and one of the project leaders. Even the most skilled researchers must make subjective choices that have a huge impact on the result they find.

But these disparate results don’t mean that studies can’t inch us toward truth. “On the one hand, our study shows that results are heavily reliant on analytic choices,” Uhlmann told me. “On the other hand, it also suggests there’s a there there. It’s hard to look at that data and say there’s no bias against dark-skinned players.” Similarly, most of the permutations you could test in the study of politics and the economy produced, at best, only weak effects, which suggests that if there’s a relationship between the number of Democrats or Republicans in office and the economy, it’s not a strong one.

The last paragraph is simply appalling. This is precisely the sort of conclusion you can’t draw. Some methods got marginally “significant” results — if you define “significance” by the ridiculously weak 5% threshold — and others didn’t. The reason p-hacking is a problem is that people may be choosing their methods (either consciously or otherwise) to lead to their preferred conclusion. If that’s really a problem, then you can’t draw any valid conclusion from the fact that these analyses tended to go one way.

As long as I’m whining, there’s this:

Take, for instance, naive realism — the idea that whatever belief you hold, you believe it because it’s true.

Naive realism means different things to psychologists and philosophers, but this isn’t either of them.

Anyway, despite my complaining, there’s some good stuff in here.