If, like me, you like arguments about English grammar and usage, you frequently come across the distinction between “prescriptivists” and “descriptivists.” Supposedly, prescriptivists are people who think that grammatical rules are absolute and unchanging. Descriptivists, on the other hand, supposedly think that there’s no use in rules that tell people how they should speak and write, and that all that matters is the way people actually do speak and write. As the story goes, descriptivists regard prescriptivists as persnickety schoolmarms, while prescriptivists regard descriptivists as people with no standards who are causing the language to go to hell in a handbasket.

In fact, of course, these terms are mostly mere invective. If you call someone either of these names, you’re almost always trying to tar that person with an absurd set of beliefs that nobody actually holds.

A prescriptivist, in the usual telling, is someone who thinks that all grammatical rules are set in stone forever. (Anyone who actually believed this would presumably have to speak only in Old English, or better yet, proto-Indo-European.) A descriptivist, on the other hand, is supposedly someone who thinks that all ways of writing and speaking are equally valid, and that we therefore shouldn’t teach students to write standard English grammar.

I can’t claim that there is nobody who believes either of these caricatures — I’m old enough to have learned that there’s someone out there who believes pretty much any foolish thing you can think of — but I do claim that practically nobody you’re likely to encounter when wading into a usage debate fits them.

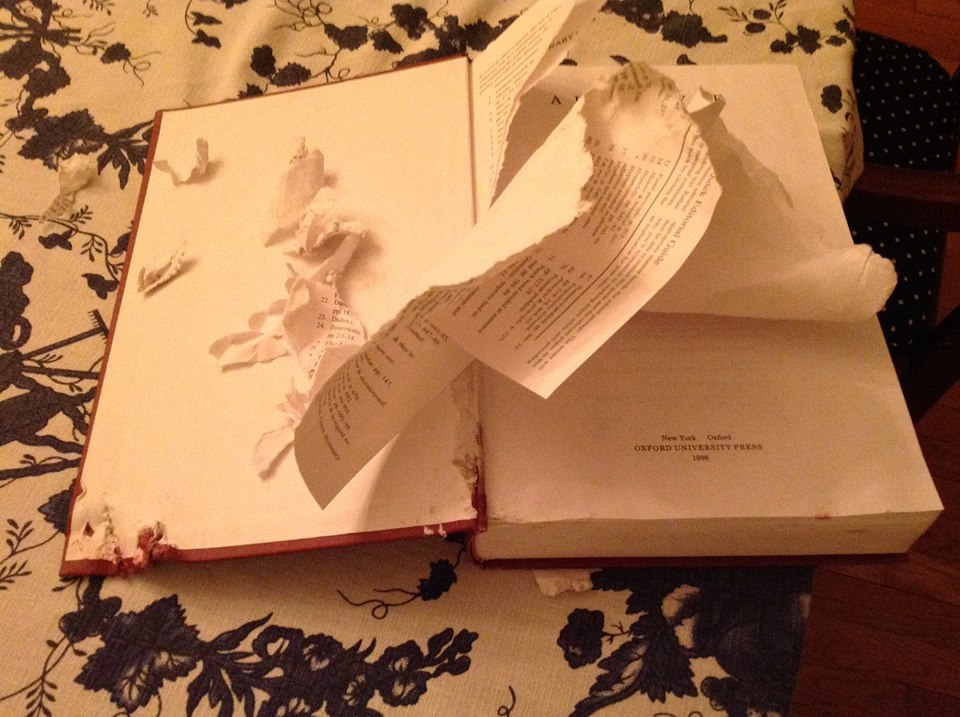

I was reminded of all this when listening to an interview with Bryan Garner, author of Modern American Usage, which is by far the best usage guide I know of. Incidentally, I’m not the only one in my household who likes Garner’s book: my dog Nora also devoured it.

Like many people, I first learned about Garner in David Foster Wallace’s essay “Authority and American Usage,” which originally appeared in Harper’s and was reprinted in his book Consider the Lobster. Wallace’s essay is very long and shaggy, but it’s quite entertaining (if you like that sort of thing) and has some insightful observations. The essay is nominally a review of Garner’s usage guide, but it turns into a meditation on the nature of grammatical rules and their role in society and education.

From his book, Garner strikes me as a clear thinker about lexicographic matters, so I was disappointed to hear him go in for the most simpleminded straw-man caricatures of the hated descriptivists in that interview.

Garner’s scorn is mostly reserved for Steven Pinker. Pinker is pretty much the arch-descriptivist, in the minds of those people for whom that is a term of invective. But that hasn’t stopped him from writing a usage guide, in which he espouses some (but not all) of the standard prescriptivist rules. Pinker’s and Garner’s approaches actually have something in common: both try to give reasons for the various rules they advocate, rather than simply issuing fiats. But because Garner thinks of Pinker as a loosy-goosy descriptivist, he can’t bring himself to engage with Pinker’s actual arguments.

Garner says that Pinker has “flip-flopped,” and that his new book is “a confused book, because he’s trying to be prescriptivist while at the same time being descriptivist.” As it turns out, what he means by this is that Pinker has declined to nestle himself into the pigeonhole that Garner has designated for him. I’ve read all of Pinker’s general-audience books on language — his first such book, The Language Instinct, may be the best pop-science book I’ve ever read — and I don’t see the new one as contradicting the previous ones. Pinker has never espoused the straw-man position that all ways of writing are equally good, or that there’s no point in trying to teach people write more effectively. Garner thinks that that’s what a descriptivist believes, and so he can’t be bothered to check.

The Language Instinct has a chapter on “language mavens,” which is the place to go for Pinker’s views on prescriptive grammatical rules. (That chapter is essentially reproduced as an essay published in the New Republic.) Garner has evidently read this chapter, as he mockingly summarizes Pinker’s view as “You shouldn’t criticize the way people use language any more than you should criticize how whales emit their moans,” which is a direct reference to an analogy found in this chapter. But he either deliberately or carelessly misleads the reader about its meaning.

Pinker is not saying that there are no rules that can help people improve their writing. Rather, he’s making the simple but important point that scientists are more interested in studying language as a natural system (how do people talk) than in how they should talk.

So there is no contradiction, after all, in saying that every normal person can speak grammatically (in the sense of systematically) and ungrammatically (in the sense of nonprescriptively), just as there is no contradiction in saying that a taxi obeys the laws of physics but breaks the laws of Massachusetts.

Pinker is a descriptivist because, as a scientist, he’s more interested in the first kind of rules than the second kind. It doesn’t follow from this that he thinks the second kind don’t or shouldn’t exist. A physicist is more interested in studying the laws of physics than the laws of Massachusetts, but you can’t conclude from this that he’s an anarchist.

(Pinker does unleash a great deal of scorn on the language mavens, not for saying that there are guidelines that can help you improve your writing, but for saying specific stupid things, which he documents thoroughly and, in my opinion, convincingly.)

Although Pinker is the only so-called descriptivist Garner mentions by name, he does tar other people by saying, “There was this view, in the mid-20th century, that we should not try to change the dialect into which somebody was born.” He doesn’t indicate who those people were, but my best guess is that this is a reference to the controversy that arose over Webster’s Third in the 1950s. If so, it sounds as if Garner (like Wallace) is buying into a mythologized version of that controversy.

It seems to me that the habit of lumping people into the “prescriptive” and “descriptive” categories is responsible for Garner’s inability to pay attention to what Pinker et al. are actually saying (and for various other silly things he says in this interview). All sane people agree with the prescriptivists that some ways of writing are more effective than others and that it’s worthwhile to try to teach people what those ways are. All sane people agree with the descriptivists that some specific things written by some language “experts” are stupid, and that at least some prescriptive rules are mere shibboleths, signaling membership in an elite group rather than enhancing clarity. All of the interesting questions arise after you acknowledge that common ground, but if you start by dividing people up according to a false dichotomy, you never get to them.

Hence my prescription.

Nice essay. A somewhat off-topic question:

“I’ve read all of Pinker’s general-audience books on language — his first such book, The Language Instinct, may be the best pop-science book I’ve ever read”

What do you think of his writing on evolutionary biology, e.g. his book The Blank Slate?