A recent article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences presents results of a study on fraud in science. The abstract:

A detailed review of all 2,047 biomedical and life-science research articles indexed by PubMed as retracted on May 3, 2012 revealed that only 21.3% of retractions were attributable to error. In contrast, 67.4% of retractions were attributable to misconduct, including fraud or suspected fraud (43.4%), duplicate publication (14.2%), and plagiarism (9.8%). Incomplete, uninformative or misleading retraction announcements have led to a previous underestimation of the role of fraud in the ongoing retraction epidemic. The percentage of scientific articles retracted because of fraud has increased ∼10-fold since 1975. Retractions exhibit distinctive temporal and geographic patterns that may reveal underlying causes.

The New York Times picked up the story, and my sort-of-cousin Robert pointed out a somewhat alarmist blog post at the Discover magazine web site, with the eye-grabbing title “The real end of science.”

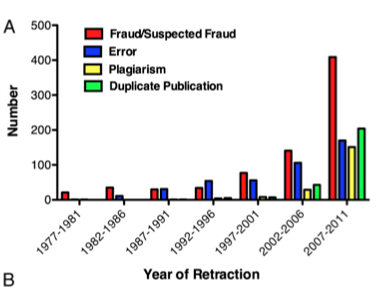

The blog post highlights Figure 1(a) from the paper, which shows a sharp increase in the number of papers being retracted due to fraud:

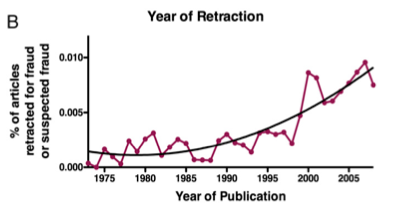

Unless you know something about how many papers were indexed in the PubMed database, of course, you can’t tell anything from this graph about the absolute scale of the problem: is 400 articles a lot or not? The sharp increase looks surprising, but even that’s hard to interpret, because the number of articles published has risen sharply over time. To me, the figure right below this one is more informative:

This is the percentage of all published articles indexed by PubMed that were retracted due to fraud or suspected fraud. In the worst years, the number is about 0.01% — that is, one article in 10000 is retracted due to fraud. That number does show a steady growth over time, by about a factor of 4 or 5 since the 1970s.

So how bad are these numbers? I think it’s worthwhile to split the question in two:

- Is the present-day level of fraud alarmingly large?

- Is the increase over time worrying?

I think the answer to the first question is a giant “It depends.” Specifically, it depends on what fraction of fraudulent papers get caught and retracted. If most frauds are caught, so that the actual level of fraud is close to 0.01%, then I’d say there’s no problem at all: we could live with a low level of corruption like that just fine. If only one case in 1000 is caught, so that 0.01% detected fraud means 10% actual fraud, then the system is rotten to its core. I’m sure the truth is somewhere in between those two, but I don’t know where in between.

I think that the author of that end-of-science blog post is more concerned about question 2 (the rate of increase of fraud over time). From the post:

Science is a highly social and political enterprise, and injustice does occur. Merit and effort are not always rewarded, and on occasion machination truly pays. But overall the culture and enterprise muddle along, and are better in terms of yielding a better sense of reality as it is than its competitors. And yet all great things can end, and free-riders can destroy a system. If your rivals and competitors and cheat and getting ahead, what’s to stop you but your own conscience? People will flinch from violating norms initially, even if those actions are in their own self-interest, but eventually they will break. And once they break the norms have shifted, and once a few break, the rest will follow.

Does the increase in fraud documented in this paper mean that we’re getting close to a breakdown of the ethos of science? I’m not convinced. First, the increase looks a lot more dramatic in the (unnormalized) first plot than in the (normalized) second one. The blog post reproduces the first but not the second, even though the second is the relevant one for answering this question.

The normalized plot does show a significant increase, but it’s hard to tell whether that increase is because fraud is going up or because we’re getting better at detecting it. From the PNAS article:

A comprehensive search of the PubMed database in May 2012 identified 2,047 retracted articles, with the earliest retracted article published in 1973 and retracted in 1977. Hence, retraction is a relatively recent development in the biomedical scientific literature, although retractable offenses are not necessarily new.

In the old days, people don’t seem to have retracted, for any reason. If the culture has shifted towards expecting retraction when retraction is warranted, then the numbers would go up. That’s not the whole story, because the ratio of fraud-retractions to error-retractions changed over that period, but it could easily be part of it.

It’s also plausible that we’re detecting fraud more efficiently than we used to. A lot of the information about fraud in this article comes from the US Government’s Office of Research Integrity, which was created in 1992. Look at the portion of that graph before 1992, and you won’t see strong evidence of an increase. Maybe fraud detections are going up because we’re trying harder to look for it.

Scientific fraud certainly occurs. Given the incentive structure in science, and the relatively weak policing mechanisms, it wouldn’t be surprising to find a whole lot of it. In fact, though, it’s not clear to me that the evidence supports the conclusion of either widespread or rapidly-increasing fraud.

Probably electronic publication makes it easier to detect now.

Note that arXiv now informs the reader when a paper has a significant overlap in text with a paper by other authors.