Phil Plait has a pretty good jeremiad on the infamous Creationist 4th-grade science quiz:

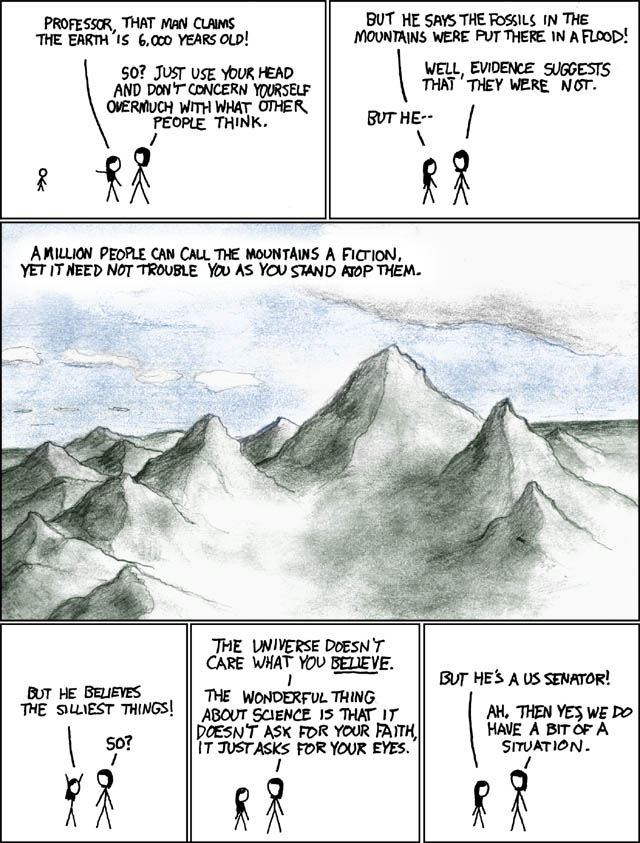

The thing that gets me is not the issue of legality here, nor necessarily who is promoting it. What really makes my heart sink is the reality that this is actually being taught to young children. Kids are natural scientists; they want to see and explore and categorize and ask “why?” until they understand everything. And we, as adults, as caretakers, have a solemn responsibility to nurture that impulse and to answer them in as honest a way as possible, encouraging them to seek more answers—and more questions—themselves. That’s how we learn.

But this? This isn’t learning. It’s indoctrination. It’s the exact opposite of inquisitiveness: it’s children being told what the creationists want the answer to be, despite the evidence. And it’s not just that these children are being told something that’s wrong; it’s that they are also told to simply accept it and deny the actual evidence they come across.

If you haven’t seen the quiz, you can go to Snopes, among other places, for details. Snopes is of course the cataloguer and debunker of urban legends. They have a piece about this because, when the quiz first started circulating, lots of people thought it was a hoax. It always seemed utterly plausible to me that it was real, unfortunately.

In addition to lamenting, Plait provides some links to useful resources about evolution and creationism, including one from Nature called 15 Evolutionary Gems, which I hadn’t seen before and which looks good.

On a related note, Eugenie Scott, longtime head of the National Center for Science Education, is retiring. Plait again:

Genie has been a tireless fighter against nonsense; for years as head of NCSE she kept up with and kept after people who try to wedge religious indoctrination into schools. Whether it was creationism or its mutant offspring Intelligent Design, she was always there, in the courtroom or on stage or writing about it. The NCSE is a shining example of what needs to be done in this never-ending affair.

That reminds me that I haven’t sent any money to the NCSE for a while. I’m going to do that. You should too.