by Tucker Shelley

Tucker Shelley is a rising senior at UR from Burlington, Vermont. He is a member of the Theta Chi fraternity on campus. In his free time, Tucker prefers staying active and listening to good music. This is his first summer working on the Race & Racism Project and will continue similar work next semester for Dr. Maurantonio in the “Digital Memory and the Archive” course.

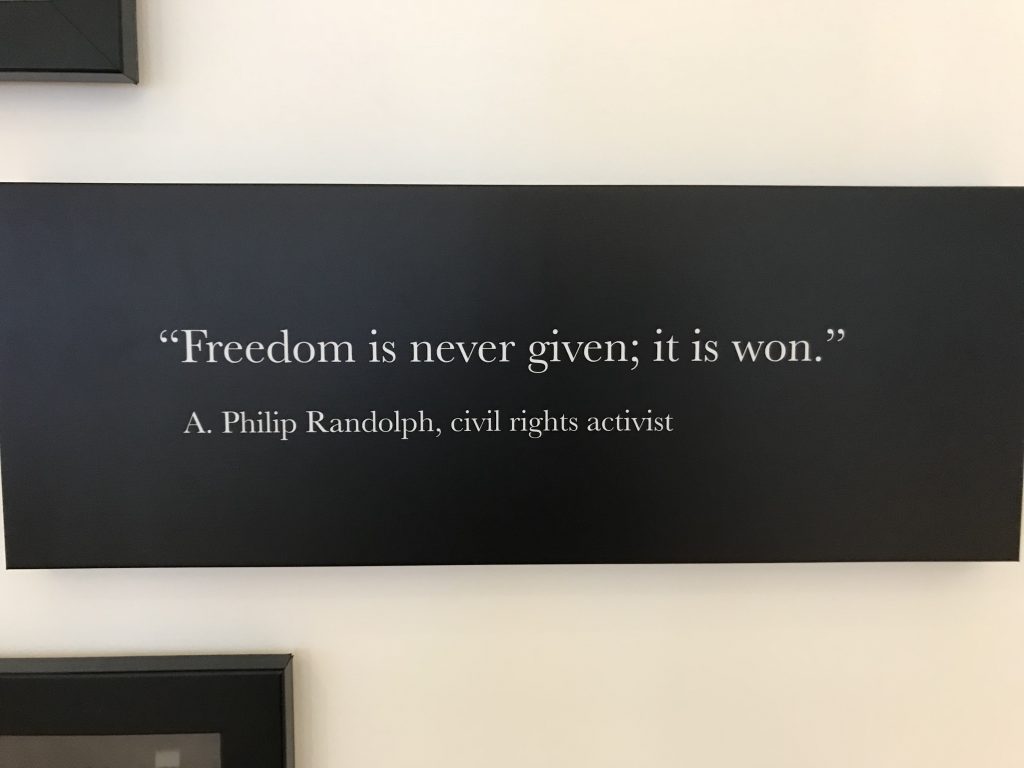

The Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site is a house museum in the mansion that Maggie Lena Walker resided in. Walker was a public figure, civil rights activist, teacher, and the first black, female bank owner. The goal of this house museum is to take you back to Walker’s time and see how life might’ve been for her through the lens of her abode. This house is in Jackson Ward, a historically black neighborhood in downtown Richmond. More specifically, the home is on 2nd Street which was previously known as “The Deuce.” It was a bustling street that was the center of almost all black commerce, warranting its other nicknames: “Black Wall Street” and “Harlem of the South.” Maggie L. Walker embodied this mentality by becoming the first female of any race to charter a bank in the United States. One day in mid-June, I made a visit to this museums in hopes of an enjoyable experience in which I learned something. While I did learn quite a lot about the history of The Deuce and Maggie Walker’s history, it was a rather dull showing.