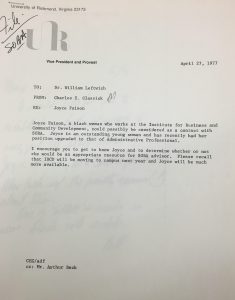

On April 27, 1977, university provost, Dr. Charles Glassick, sent a short memo to the then-vice president of student affairs, William Leftwich, about Joyce Faison. Faison was a black woman, who worked for the Institute for Business and Community Development. The university-sponsored institute was located downtown on Grace and Lombardy Streets and started in 1963 to help resolve issues between businesses and communities with higher education resources. At the time, Faison had recently been promoted to an administrative professional position at the institute and Glassick believed that she could be “considered as a contact for SOBA (Student Organization for Black Awareness).” Glassick goes on to prompt Leftwich to reach out to Faison and determine whether she would be a suitable sponsor for SOBA. Glassick also mentioned that the Institute for Business and Community Development was moving to campus the following year and implied that Faison would be more available to them.

On April 27, 1977, university provost, Dr. Charles Glassick, sent a short memo to the then-vice president of student affairs, William Leftwich, about Joyce Faison. Faison was a black woman, who worked for the Institute for Business and Community Development. The university-sponsored institute was located downtown on Grace and Lombardy Streets and started in 1963 to help resolve issues between businesses and communities with higher education resources. At the time, Faison had recently been promoted to an administrative professional position at the institute and Glassick believed that she could be “considered as a contact for SOBA (Student Organization for Black Awareness).” Glassick goes on to prompt Leftwich to reach out to Faison and determine whether she would be a suitable sponsor for SOBA. Glassick also mentioned that the Institute for Business and Community Development was moving to campus the following year and implied that Faison would be more available to them.

On the surface, Dr. Glassick’s memo reads like a good faith effort from the administration to help SOBA advance their organizational aims but the message actually underscores larger institutional problems. Having to look to Joyce Faison, an administrator at an off-campus university-affiliated program, as a sponsor for SOBA points to the lack of black mentors on campus. White men held most high-level administrative positions and the only black faculty member was Dr. Lorenzo Simpson, a professor in the philosophy department, who joined the university in 1976. During this time black students were still fairly new to campus and that was evident in the lack of support from administrators. Instead of being provided guidance, black students had to advocate for it. The black students in SOBA had to prod the administration to make moves forward on their behalf. Black students had to bear the burden of advocacy and simply existing in a majority white space. They were stretched thin and their organization suffered as a result. SOBA members often lamented having to alter their schedule of events due to lack of resources and low attendance.

This document represents the troubling incongruity between a university that wanted to recruit black students but barely supported the black students that were already there. Black students reported that administrators sympathized with them but had no plan for creating an actual infrastructure of support. Administrators had to look for someone off campus to find a mentor for SOBA because there were so few options on campus. However, there is also no indication that Faison asked to sponsor the students but rather an assumption that because she was black she would be up for the job. They had assumed domain over her labor. It is not clear if Faison became a mentor or if the contact was ever made between her and Leftwich but what is clear and in the record is that black students carried the burden of advocating with an administration that was reactive instead of proactive to their needs.