This week on Expanding the Ivory Tower we explore the celebration of Black History Week at the University back in 1974. In this episode we consider the historical context of the event and the struggle to make it happen.

Month: January 2017

Potent and Divisive

In his final address to the nation, President Obama outlined the most imminent threats to our democracy – one of which he described as “as old as our nation itself.” He admonished the dream of a post-racial America many envisioned after his election as unrealistic. According to him, the threat of “race remains a potent and often divisive force in our society.” However, more accurately stated, he should have said racism remains a potent and often divisive force in our nation, but he didn’t. Why?

Racism is a taboo word in the public sphere. Terms like race and race relations have become euphemistic ways to talk about racism. This linguistic elision has made it so people believe talking about race is difficult and that discussing the socially constructed identifiers ascribed to different groups of people is cringe worthy and uncomfortable. In reality, talking about race is easy. When taken to be a socially constructed system of identification based on factors such as physical traits and ancestry, race is not that big of a deal. Through that lens, race is just something we all have, like a favorite sports team, or something we can all relate to, like being from a certain state.

By now you may be shaking your head and thinking to yourself that talking about being an Eagles fan or from Oklahoma is certainly a lot easier than talking about being black in America and you’re right. It is. That is because when talking about being black in America the conversation that follows is not simply about race. The conversation is also about racism. Racism is like race’s evil twin brother that lurks in the shadows, seeps through the cracks, and permeates nearly every facet of American society. Racism involves the unequal distribution of resources, unbalanced power dynamics, and unfettered privilege afforded to some based upon the system of identification that is race. While the two are closely related they are not the same but since they are so interconnected conversations that involve racism are often mistaken for conversations that are just about race.

President Obama engaged in the sort of rhetorical fodder that neglects to call racism by its name. On such a basic level he failed to get real about the reality of race and racism in America. To refer to race as a potent, divisive force in society and to not speak the word racism except when qualified by the word reverse, Obama inadvertently contributed to the very threat he warned against.

Open Forum with the Race and Racism at the University of Richmond Project

Join the Race & Racism at the University of Richmond Project on Wednesday, January 18 from 4-5:30 PM in Jepson Hall Room 109 in an Open Forum to discuss the project’s partnership with Free Egunfemi, founder of Untold RVA. Untold RVA’s pod marker project seeks to connect individuals with sites of self-determined history throughout the city, honoring Richmond’s abolitionists, women’s rights activists, creative change agents, and more. The Race & Racism Project’s partnership with Untold RVA seeks to bring the pod marker project to our campus in order to make the history of resistance and change more visible and spark continued conversation and action for an equitable and inclusive community.

This Open Forum seeks to begin a conversation about campus history and current events to create pod markers that will be visible to all members of the UR community and visitors. No knowledge of UR history is necessary to attend, as the forum seeks to gain feedback and create a dialogue about who, what, and how commemoration will work. We will also speak about opportunities for collaboration with Untold RVA via independent studies and summer fellowships as the Richmond-centered project expands.

The Unfinished Work

This week our Post-Baccalaureate fellow, Victoria Charles, takes to the studio to reflect on the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King. More specifically, she dives into how Dr. King is remembered here at the University of Richmond. To do so, Victoria spoke with Lisa Miles, associate director of Common Ground and member of UR’s MLK Day planning committee, about how the University commemorates King today.

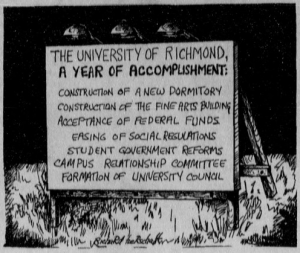

This Week in the Archive: A Year Of Accomplishment

The end of a year, whether that be calendar or academic, is often framed as cause for reflection. Yet end-of-the-year roundups do more than just look back. They consider the defining events of the year through the lens of whoever is writing. Those musings say as much about the events of the year as they do the positionality of the writer. When we take a look at what is included and more importantly what is left out we can unearth valuable subtext. Opportunely, this method applies to archival work as well. Take for example this cartoon published in The Collegian on May 17, 1968. The image depicts signage that reads “The University of Richmond, A Year of Accomplishment”. The cartoonist chose to frame what he deemed the most significant events of the academic year as accomplishments. The claim to accomplishments begs the question, accomplishments for whom? If we take a closer look at the first three: the construction of a new dormitory, the construction of the fine arts building, and the acceptance of federal funds, the answer to that question becomes complex.

The end of a year, whether that be calendar or academic, is often framed as cause for reflection. Yet end-of-the-year roundups do more than just look back. They consider the defining events of the year through the lens of whoever is writing. Those musings say as much about the events of the year as they do the positionality of the writer. When we take a look at what is included and more importantly what is left out we can unearth valuable subtext. Opportunely, this method applies to archival work as well. Take for example this cartoon published in The Collegian on May 17, 1968. The image depicts signage that reads “The University of Richmond, A Year of Accomplishment”. The cartoonist chose to frame what he deemed the most significant events of the academic year as accomplishments. The claim to accomplishments begs the question, accomplishments for whom? If we take a closer look at the first three: the construction of a new dormitory, the construction of the fine arts building, and the acceptance of federal funds, the answer to that question becomes complex.

The construction of the new dormitory was important because some students had been living in temporary barracks that were pre-war, hazardous, and prone to fire. However, this new housing option was only available to male students despite the fact that female students were also in need of improved housing. In fact, an editorial published in the same Collegian issue as this cartoon lamented the overcrowding and lack of amenities available in one of the main residence halls for women. The construction of the fine arts building symbolized a triumph of fundraising and dedication to the advancement of the arts at the University. The construction of the building also underscored the problem of the University paying its workers too little. In fact, work on the building was halted by a worker’s strike started by laborers at the heating plant. Electricians working in the fine arts building participated in the strike as a sign of solidarity with the heating plant workers. The strike eventually ended but did not result in higher wages for the workers. The acceptance of federal funds meant that more money would be available for use other than capital construction but also meant that the University had to comply with federal statutes such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in any program receiving federal funds. Despite having integrated downtown night courses in 1964, the University of Richmond remained segregated on its main campus until the fall of 1968, months after this cartoon was published.

The cartoonist chose to portray the year as one of progress without acknowledging the tenuous nature of the accomplishments he highlighted. He failed to consider that what was good for some was, in fact, harmful to others, that his purview of accomplishments and progress existed in a space where black students had not yet been welcome.