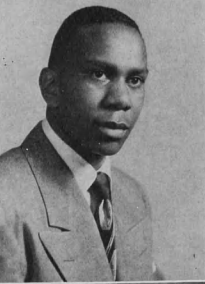

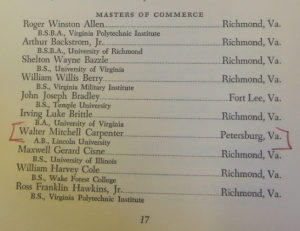

On June 8,1964 Walter Carpenter became the first African-American to receive a degree from the University of Richmond through the institution’s University College division. This overlooked historic occurrence predates the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the arrival of Barry Greene (the first black undergraduate student) on campus in 1968. Yet I would urge caution against identifying this milestone as an indication of progressiveness on the part of the university. Instead, Walter Carpenter’s story underscores the cumbersomeness of the university’s segregation policy.

On June 8,1964 Walter Carpenter became the first African-American to receive a degree from the University of Richmond through the institution’s University College division. This overlooked historic occurrence predates the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the arrival of Barry Greene (the first black undergraduate student) on campus in 1968. Yet I would urge caution against identifying this milestone as an indication of progressiveness on the part of the university. Instead, Walter Carpenter’s story underscores the cumbersomeness of the university’s segregation policy.

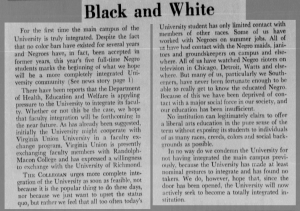

When Carpenter began taking a graduate class sponsored by the university at Ft. Lee, University of Richmond administrators did not revoke their pro-segregationist stance. Ft. Lee, a military post in Virginia, and the rest of the armed forces formally integrated in 1948 under Executive Order 9981. Since the class was being held at Ft. Lee it is presumed that the university did not have jurisdiction over who was allowed to enroll. Although Carpenter was a civilian employee, he benefitted from desegregation at Ft. Lee. For an unknown reason, Carpenter’s class was eventually shifted to University College, the University of Richmond’s downtown division, in 1962. At its semi-annual meeting in February of 1963, the university’s Board of Trustees reaffirmed the school’s policy of racial segregation but opened certain graduate and professional classes to black students. To the uncritical eye, it would seem that the university took a meaningful step toward openness and integration but in actuality, the university simply forged a very narrow path to progress in one place and double downed its segregation efforts everywhere else, which made for a deceptively open yet still very racist admissions policy.

In February of 1964, the university issued a statement announcing classes sponsored by the American Institute of Banking were open to black people and that 12 or more had been enrolled in classes. The Collegian article reporting this decision made no mention of Carpenter, whose course of study was not part of the American Institute of Banking. In fact, Carpenter had completed his degree requirements for the masters of commerce before the university issued the statement. The university’s statement only slightly widened the path to integration because it just opened courses sponsored by one entity. At this point University College was not completely integrated; only certain courses were, including the ones sponsored by the American Institute of Banking. Again it seems that the university was trying to give the illusion of an open admissions policy while still being pro-segregation.

In February of 1964, the university issued a statement announcing classes sponsored by the American Institute of Banking were open to black people and that 12 or more had been enrolled in classes. The Collegian article reporting this decision made no mention of Carpenter, whose course of study was not part of the American Institute of Banking. In fact, Carpenter had completed his degree requirements for the masters of commerce before the university issued the statement. The university’s statement only slightly widened the path to integration because it just opened courses sponsored by one entity. At this point University College was not completely integrated; only certain courses were, including the ones sponsored by the American Institute of Banking. Again it seems that the university was trying to give the illusion of an open admissions policy while still being pro-segregation.

Carpenter’s story is one of unanswered questions. For instance, why was Carpenter allowed to continue the class when it moved to University College? Why did the class move at all? Why did the university actually confer the degree? Did they not have the authority to withhold it?