by Cole Richard

Cole Richard is a junior from Orlando, Florida double majoring in English and Italian Studies and minoring in Linguistics. This is his first summer working on the Race & Racism project. He is also a resident assistant, DJ at the campus radio station, and student worker at the music library.

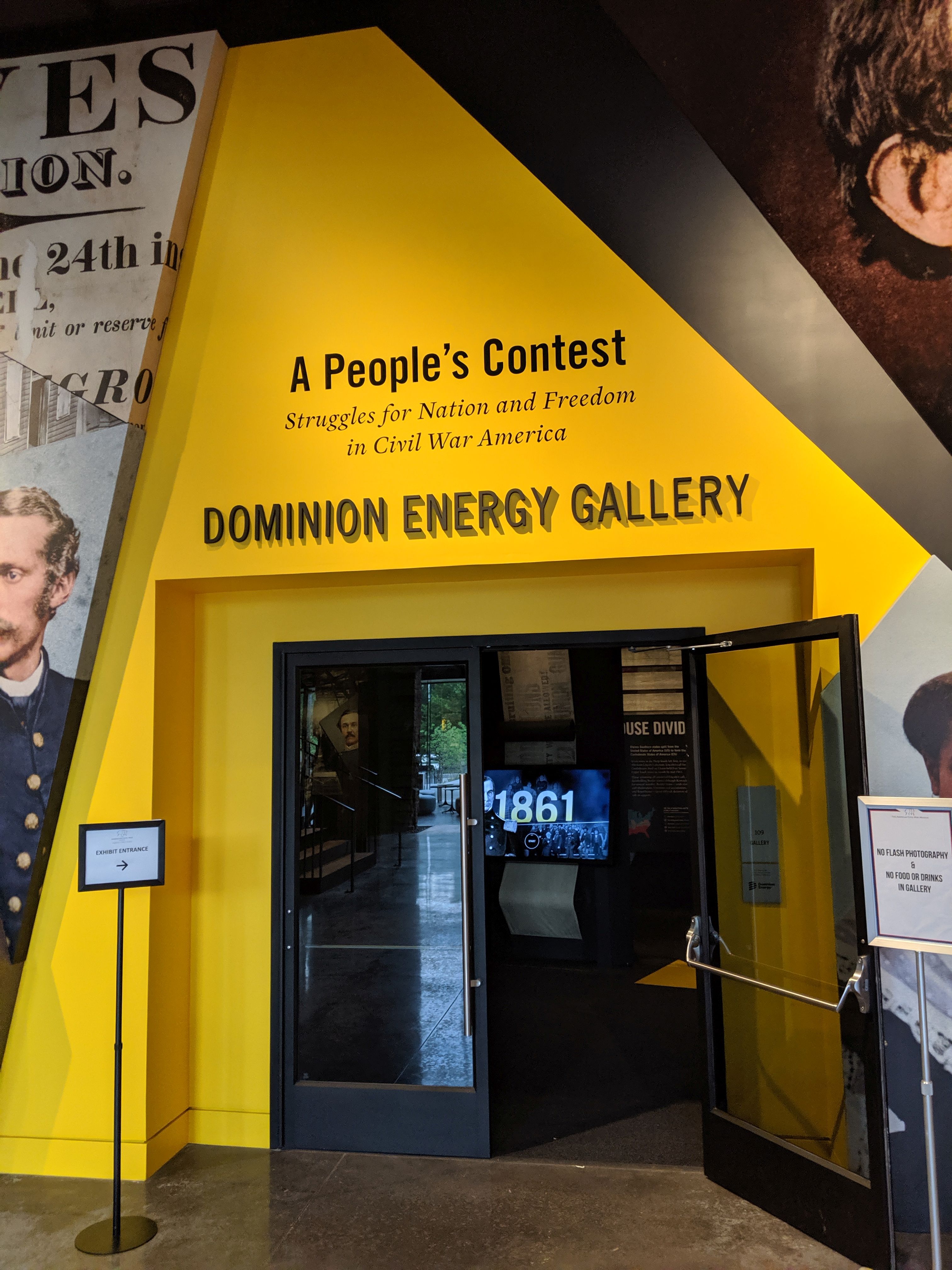

The American Civil War Museum sits on the banks of the James River, a short 20 minute walk from downtown Richmond. Located on Tredegar Street and housed in the ruins of the Tredegar Iron Works, the museum opened just a few months ago, the result of a merger between the former American Civil War Center and the Museum of the Confederacy. Although that merger took place in 2014, it took six years of work for the new combined museum to open. Drawing artifacts from both defunct institutions, the new museum’s expressed aim is “to be the preeminent center for the exploration of the American Civil War and its legacies from multiple perspectives: Union and Confederate, enslaved and free African Americans, soldiers and civilians.” This objective was apparent to me upon entering the museum.

The American Civil War Museum sits on the banks of the James River, a short 20 minute walk from downtown Richmond. Located on Tredegar Street and housed in the ruins of the Tredegar Iron Works, the museum opened just a few months ago, the result of a merger between the former American Civil War Center and the Museum of the Confederacy. Although that merger took place in 2014, it took six years of work for the new combined museum to open. Drawing artifacts from both defunct institutions, the new museum’s expressed aim is “to be the preeminent center for the exploration of the American Civil War and its legacies from multiple perspectives: Union and Confederate, enslaved and free African Americans, soldiers and civilians.” This objective was apparent to me upon entering the museum.

On the 17th floor of the VCU Medical Center’s West Hospital rests an unexpected beast. Sure, there’s a plaque in the 1st floor lobby that states the Jefferson Davis Memorial Chapel is just an elevator trip away, but, if I hadn’t done research before showing up, I certainly wouldn’t have anticipated seeing its marble archway behind an unmarked wooden door, sharing the hall with an employee-only restroom and a spattering of what appear to be used waiting-room chairs.

On the 17th floor of the VCU Medical Center’s West Hospital rests an unexpected beast. Sure, there’s a plaque in the 1st floor lobby that states the Jefferson Davis Memorial Chapel is just an elevator trip away, but, if I hadn’t done research before showing up, I certainly wouldn’t have anticipated seeing its marble archway behind an unmarked wooden door, sharing the hall with an employee-only restroom and a spattering of what appear to be used waiting-room chairs. I visited Lumpkin’s Jail (also known as the Devil’s Half Acre) and the African Burial Ground in Richmond–Lumpkin’s Jail was the largest slave-holding facility in Richmond during the mid 19th century. The jail historically has been home to the typical cruel and unusual treatment of enslaved people by Robert Lumpkin, who purchased the property and created a two story brick slave jail that held enslaved people until they were sold. After emancipation, a historically black seminary was founded and later on, a parking lot covered the area. We also visited the African Burial Ground, or, as it was originally titled in a city map, the “Burial Ground for Negroes.” As we learned from the historical markers on the site, it was a poor quality burial ground, with the danger of heavy rains washing the remnants and land into the James River, and also was where convicts were hung. After a new site opened, the grave site was abandoned and the construction of what would later become I-95 destroyed the land. In the 1990s, activists like Defenders for Freedom, Justice, & Equality and the Slave Trail Commission began working on commemorating and memorializing the site. It currently rests as a large field with information signs explaining the history, surrounded by memorials – it is not clear who left the current ones, but it is known that memorials left by survivors had disintegrated with time.

I visited Lumpkin’s Jail (also known as the Devil’s Half Acre) and the African Burial Ground in Richmond–Lumpkin’s Jail was the largest slave-holding facility in Richmond during the mid 19th century. The jail historically has been home to the typical cruel and unusual treatment of enslaved people by Robert Lumpkin, who purchased the property and created a two story brick slave jail that held enslaved people until they were sold. After emancipation, a historically black seminary was founded and later on, a parking lot covered the area. We also visited the African Burial Ground, or, as it was originally titled in a city map, the “Burial Ground for Negroes.” As we learned from the historical markers on the site, it was a poor quality burial ground, with the danger of heavy rains washing the remnants and land into the James River, and also was where convicts were hung. After a new site opened, the grave site was abandoned and the construction of what would later become I-95 destroyed the land. In the 1990s, activists like Defenders for Freedom, Justice, & Equality and the Slave Trail Commission began working on commemorating and memorializing the site. It currently rests as a large field with information signs explaining the history, surrounded by memorials – it is not clear who left the current ones, but it is known that memorials left by survivors had disintegrated with time.

For my first site visit, I chose to go to the

For my first site visit, I chose to go to the