by Cole Richard

Cole Richard is a junior from Orlando, Florida double majoring in English and Italian Studies and minoring in Linguistics. This is his first summer working on the Race & Racism project. He is also a resident assistant, DJ at the campus radio station, and student worker at the music library.

The American Civil War Museum sits on the banks of the James River, a short 20 minute walk from downtown Richmond. Located on Tredegar Street and housed in the ruins of the Tredegar Iron Works, the museum opened just a few months ago, the result of a merger between the former American Civil War Center and the Museum of the Confederacy. Although that merger took place in 2014, it took six years of work for the new combined museum to open. Drawing artifacts from both defunct institutions, the new museum’s expressed aim is “to be the preeminent center for the exploration of the American Civil War and its legacies from multiple perspectives: Union and Confederate, enslaved and free African Americans, soldiers and civilians.” This objective was apparent to me upon entering the museum.

The American Civil War Museum sits on the banks of the James River, a short 20 minute walk from downtown Richmond. Located on Tredegar Street and housed in the ruins of the Tredegar Iron Works, the museum opened just a few months ago, the result of a merger between the former American Civil War Center and the Museum of the Confederacy. Although that merger took place in 2014, it took six years of work for the new combined museum to open. Drawing artifacts from both defunct institutions, the new museum’s expressed aim is “to be the preeminent center for the exploration of the American Civil War and its legacies from multiple perspectives: Union and Confederate, enslaved and free African Americans, soldiers and civilians.” This objective was apparent to me upon entering the museum.

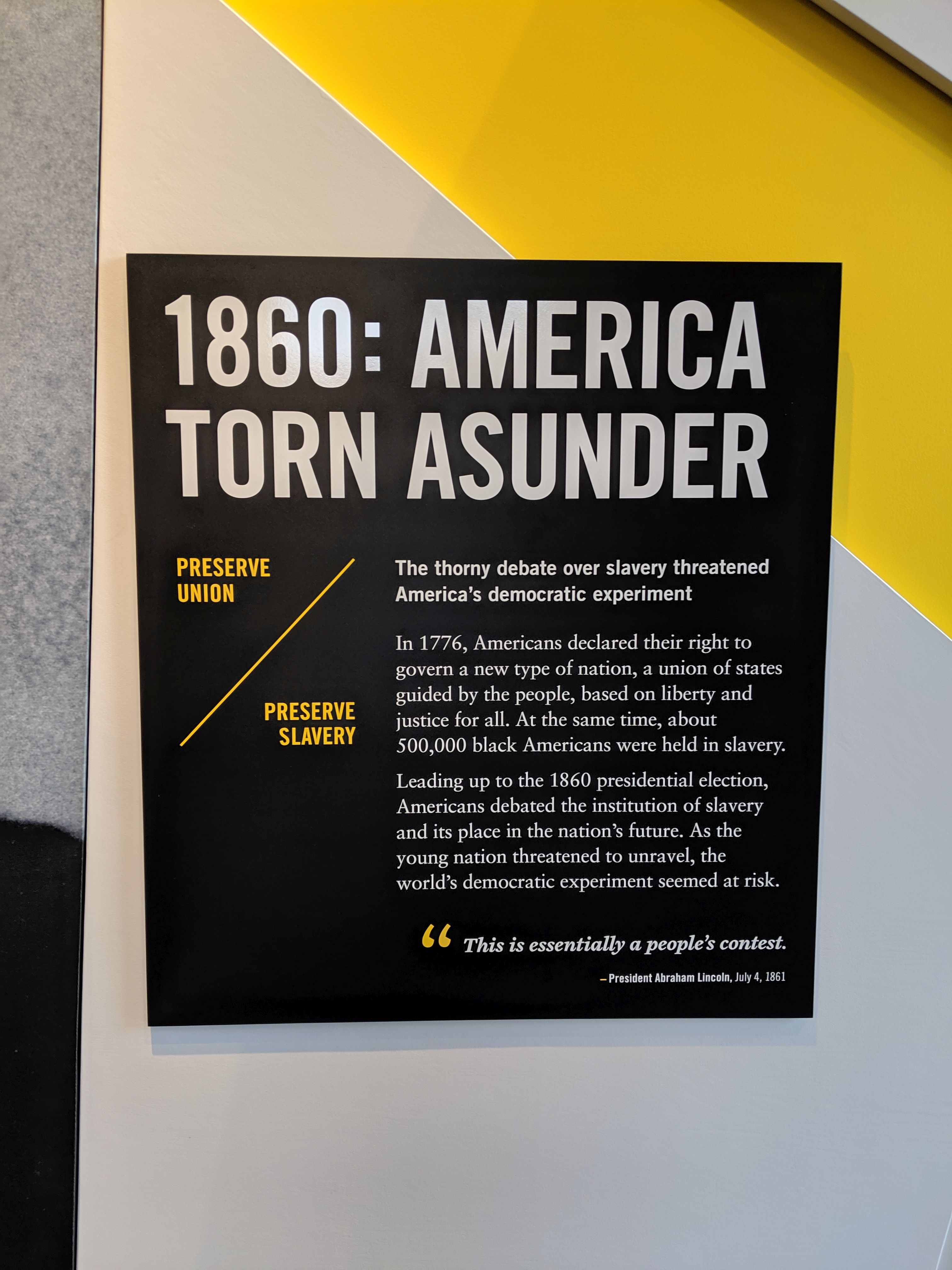

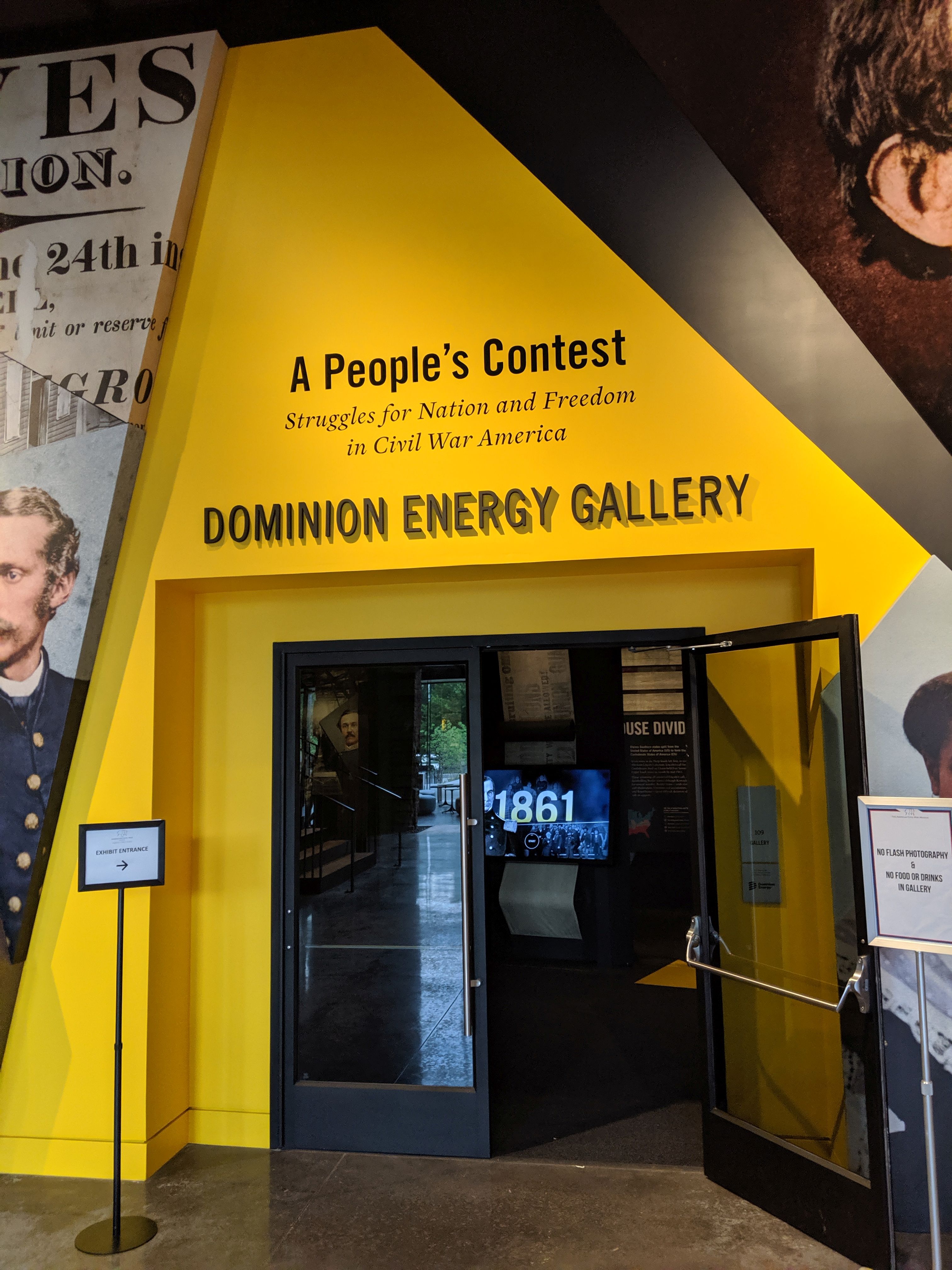

When I stepped through the preserved brick archway and into the museum, directly ahead of me were the doors to its main gallery, home to the permanent exhibit: “A People’s Contest: Struggles for Nation and Freedom in Civil War America.” The walls surrounding the exhibit’s entrance are decorated with enlarged photos of familiar faces, Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis, but also unfamiliar ones, such as a Native American soldier. It is in this area that a primary visual motif of the museum is established, one that is found on every large placard in the gallery: the presentation two opposing perspectives separated by a thin, diagonal line. In this first instance, the two sentiments read: “Preserve union” and “Preserve slavery.”

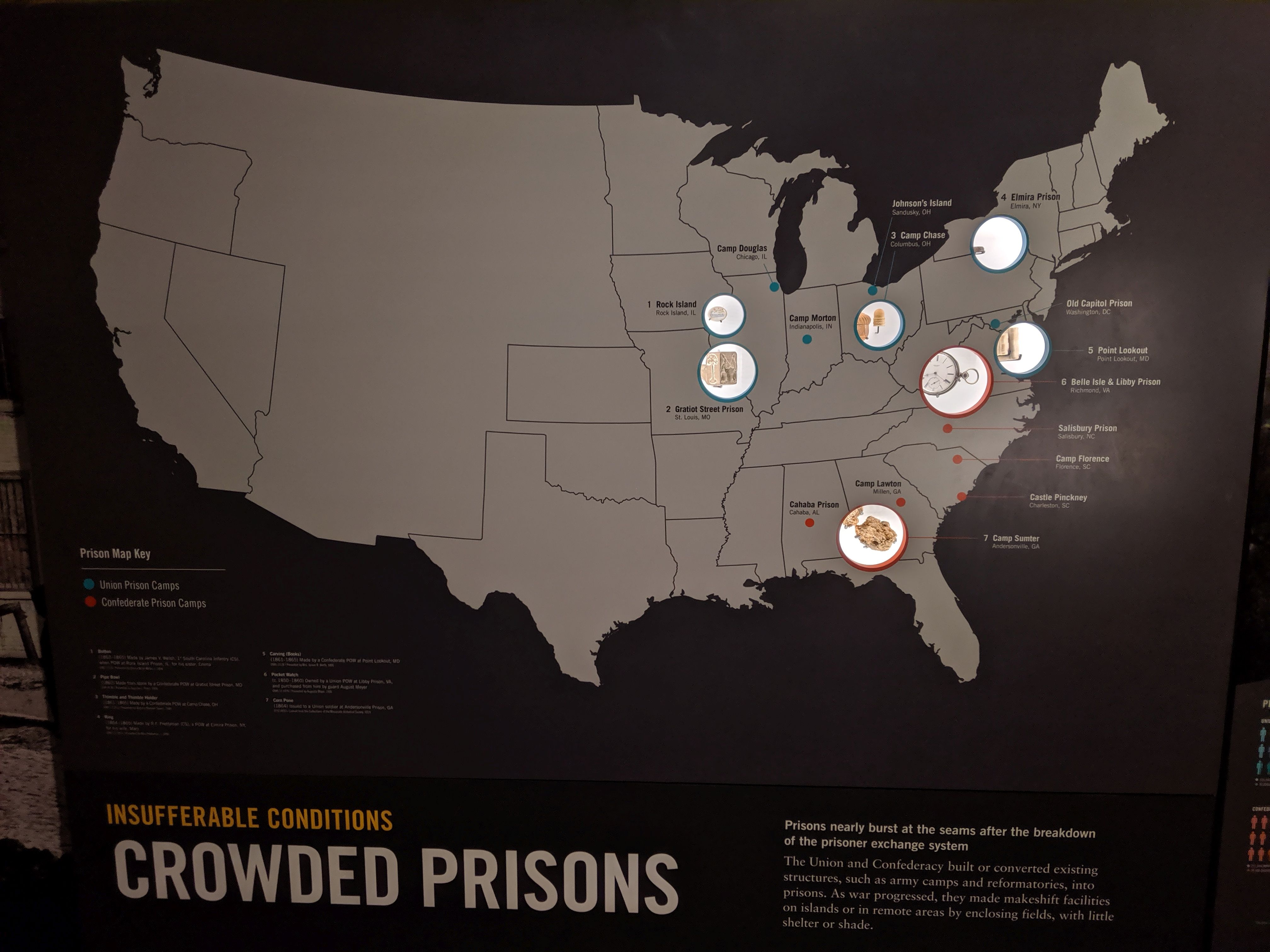

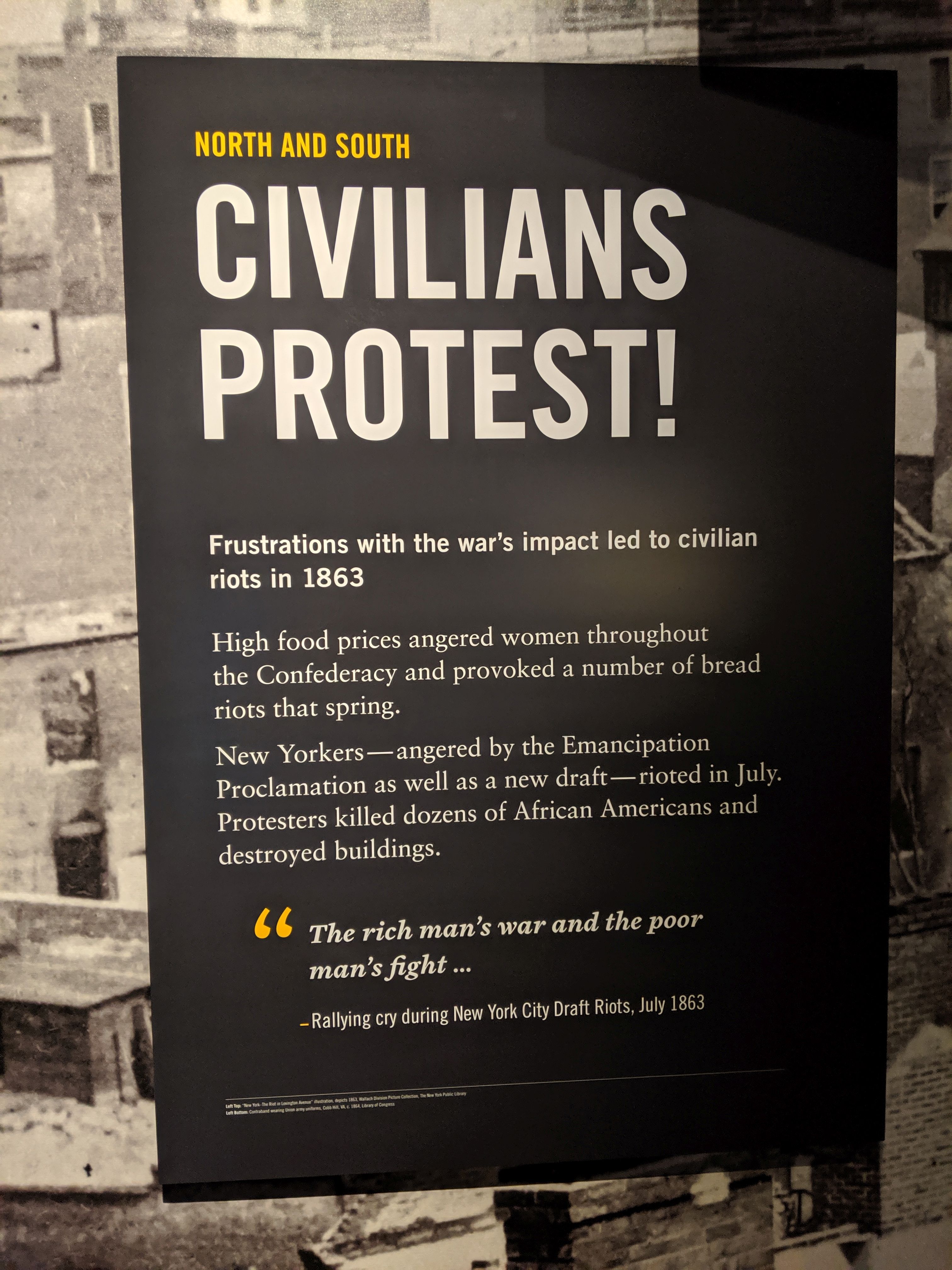

The gallery itself is primarily organized chronologically, beginning in 1861 and ending in 1865, though along the way, the focus shifts to certain experiences, with miniature exhibits that one can venture through before continuing. These often showcased Richmond-specific examples of common trends across the Union and Confederacy, such as riots and inadequate prison conditions. I was surprised to find how integrated the two museums’ collections were in this singular gallery. When I learned that the museum was the result of a merger, I expected the items to simply be housed in separate exhibits under the same roof. Instead, the gallery makes ample use of artifacts belonging to individuals from both the Union and Confederacy, and does so without relegating materials to different exhibits.

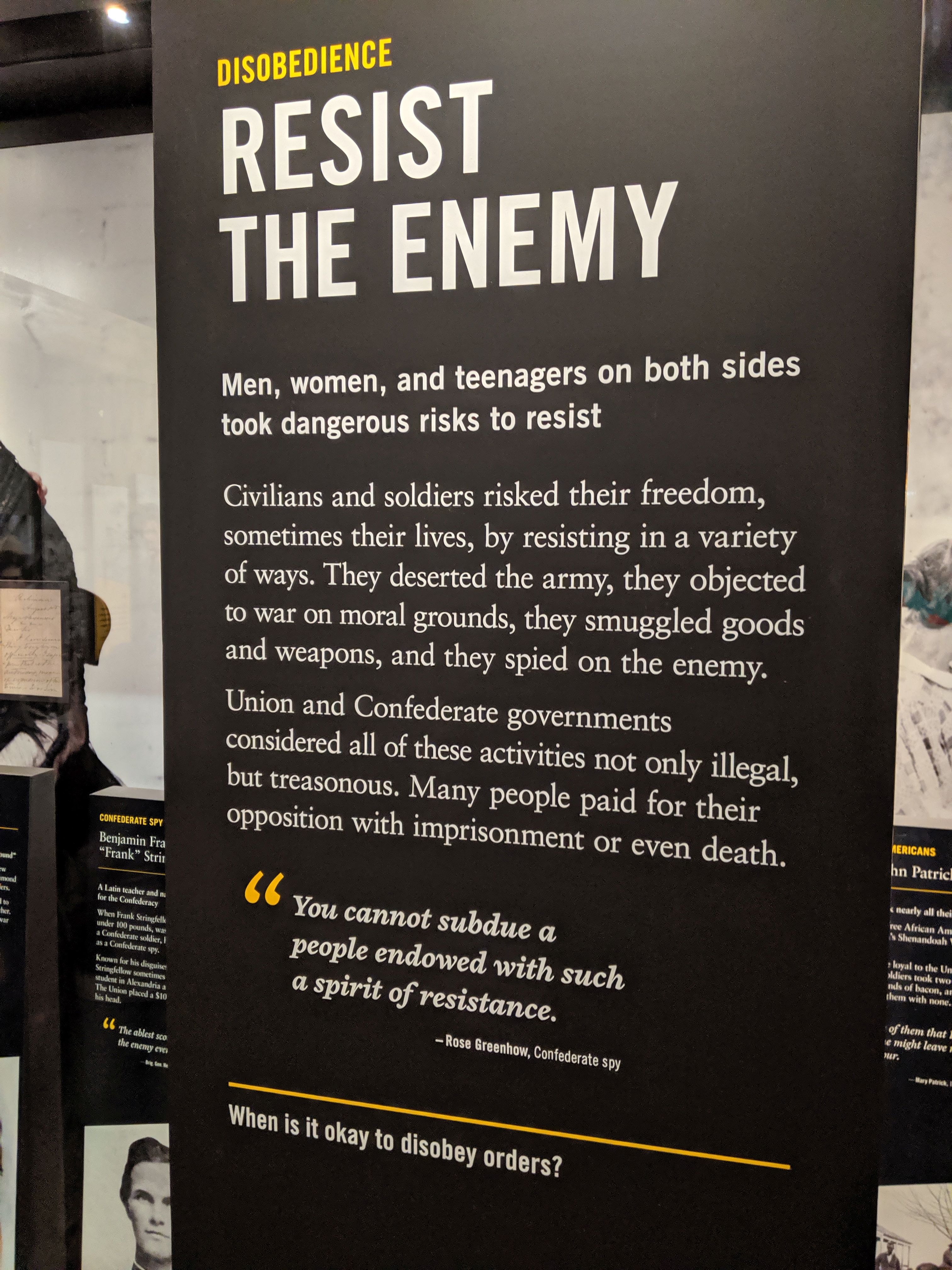

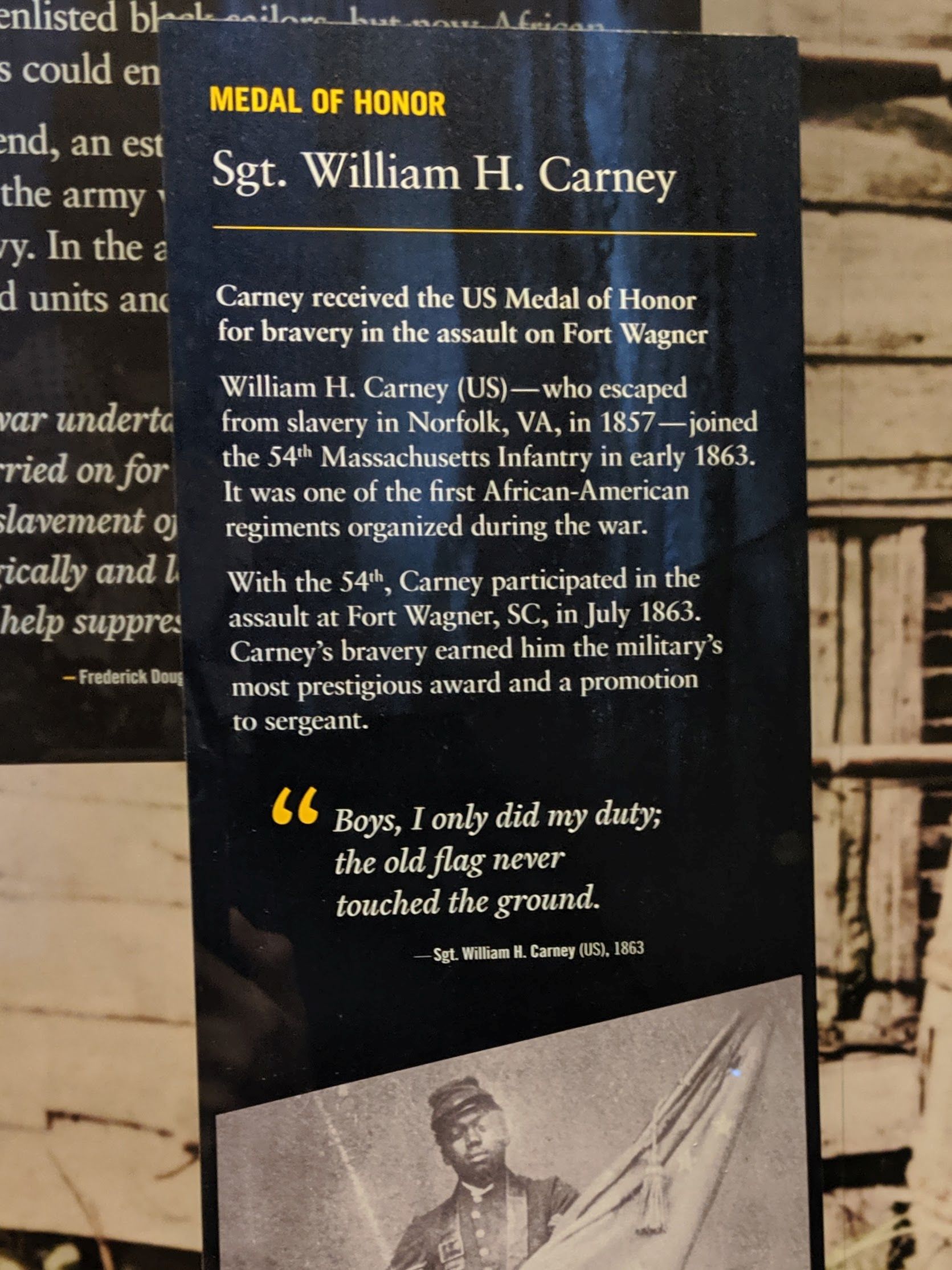

The museum manifests its mission of exploring multiple perspectives through its curation. Compared to other museums, and specifically other American war exhibits, I found a greater representation of marginalized experiences. Large portions of the gallery are devoted to contextualizing the roles of marginalized groups in the war. Two placards detail Medal of Honor recipients: Sgt. William H. Carney, an African American soldier, and Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, the first and only female Medal of Honor recipient. Importantly, however, the museum does not only feature those remembered for their valor, but those forgotten because of their resistance. A portion of the gallery is devoted to the civilians and soldiers who deserted or morally objected to the war.

The museum manifests its mission of exploring multiple perspectives through its curation. Compared to other museums, and specifically other American war exhibits, I found a greater representation of marginalized experiences. Large portions of the gallery are devoted to contextualizing the roles of marginalized groups in the war. Two placards detail Medal of Honor recipients: Sgt. William H. Carney, an African American soldier, and Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, the first and only female Medal of Honor recipient. Importantly, however, the museum does not only feature those remembered for their valor, but those forgotten because of their resistance. A portion of the gallery is devoted to the civilians and soldiers who deserted or morally objected to the war.

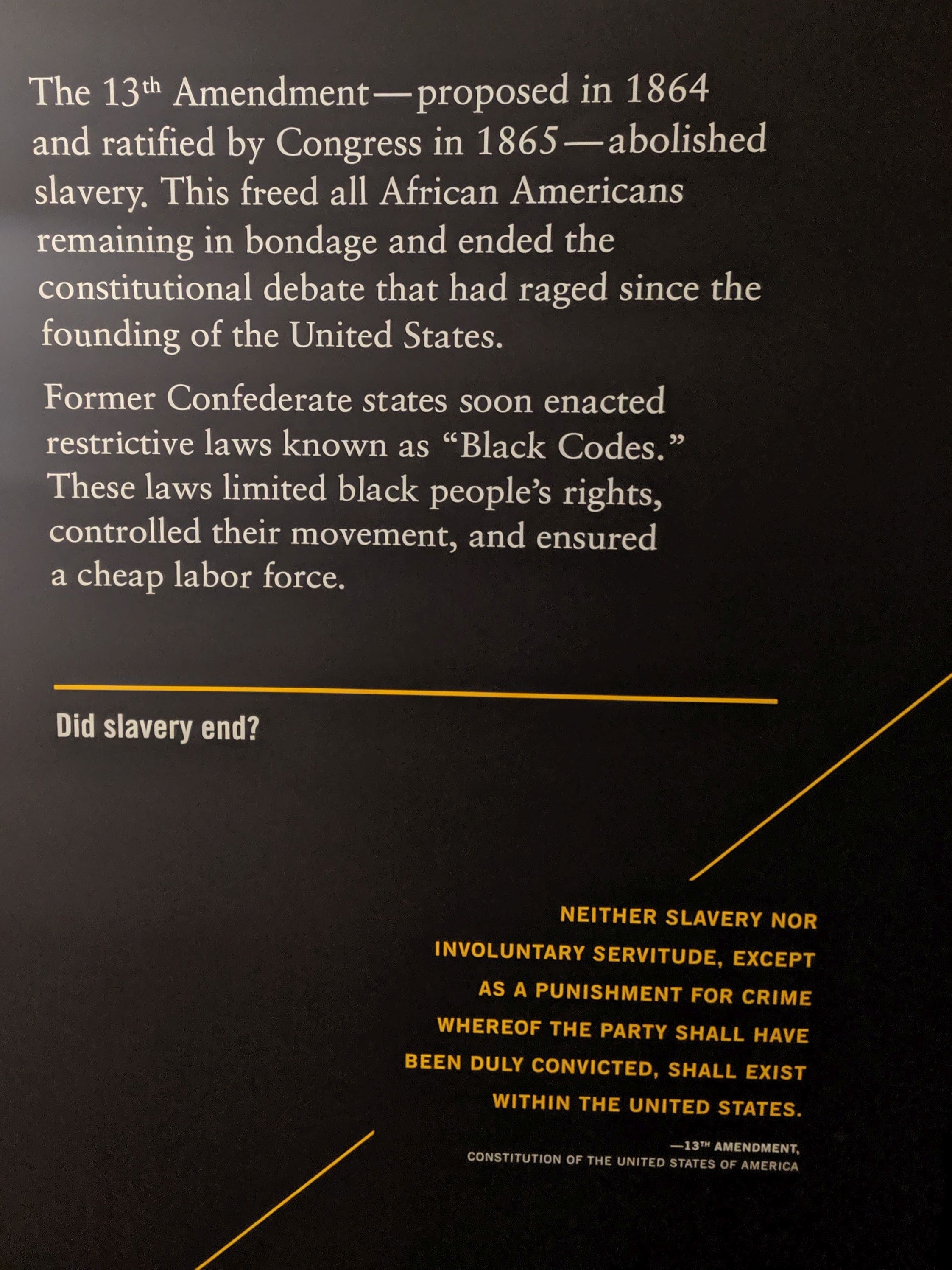

The final room of the gallery briefly covers the Reconstruction era. I entered the room and was greeted by three columns in the corners, two large portraits on opposite walls, and a Ku Klux Klan robe. The columns, each detailing one of the Civil War Amendments (13th, 14th, and 15th), were visually unlike anything else in the gallery. Each column presents an excerpt from its respective amendment, but places it squarely on the familiar diagonal line, breaking not only the line itself, but the previously established visual motif. I found this design both a striking symbol of the legal reunification of the country and a fitting design choice for the final room of the gallery.

The final room of the gallery briefly covers the Reconstruction era. I entered the room and was greeted by three columns in the corners, two large portraits on opposite walls, and a Ku Klux Klan robe. The columns, each detailing one of the Civil War Amendments (13th, 14th, and 15th), were visually unlike anything else in the gallery. Each column presents an excerpt from its respective amendment, but places it squarely on the familiar diagonal line, breaking not only the line itself, but the previously established visual motif. I found this design both a striking symbol of the legal reunification of the country and a fitting design choice for the final room of the gallery.

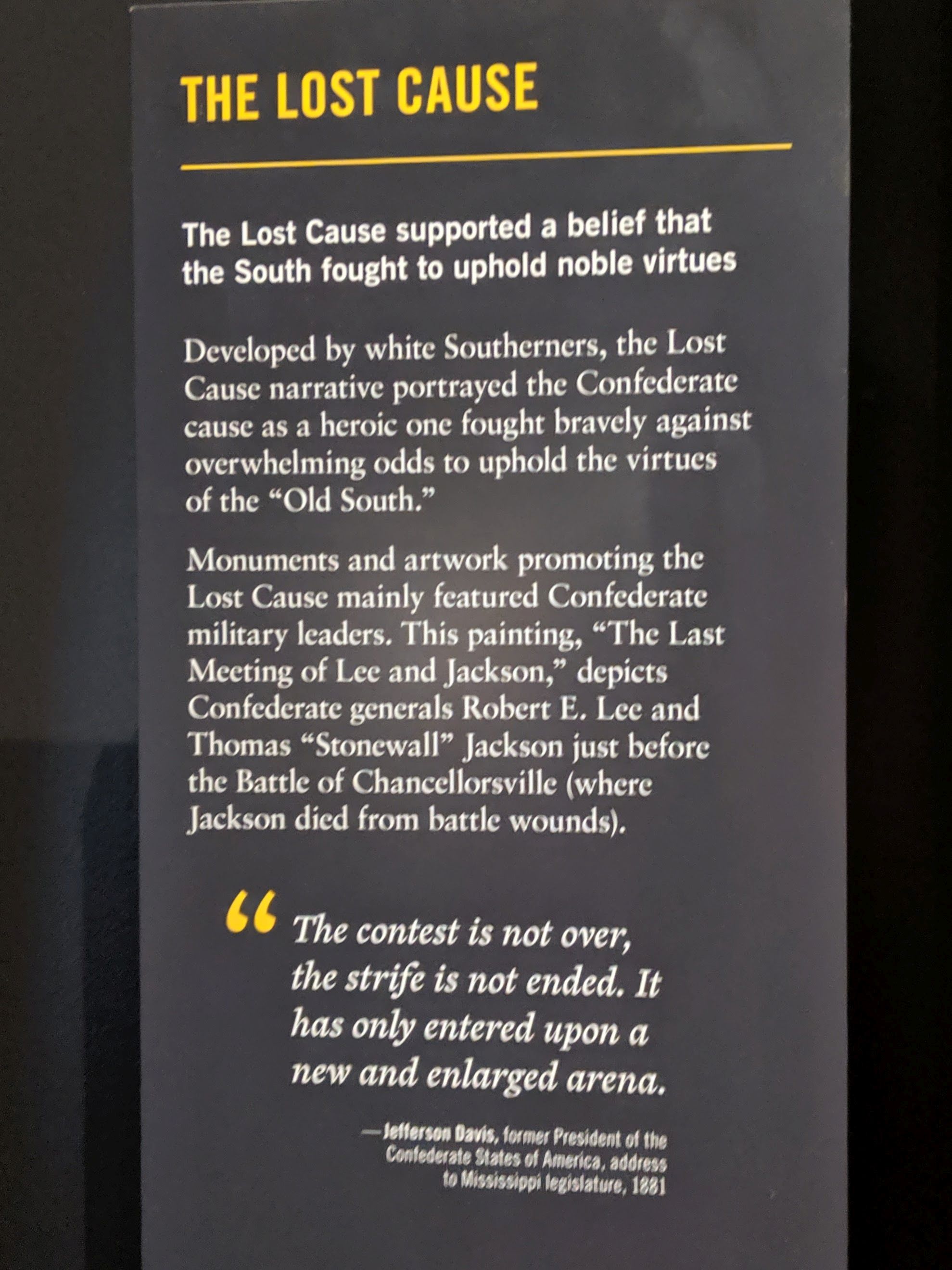

However, I found the limited space devoted to the Reconstruction era disappointing. A single placard gave a short description of Lost Cause ideology, notably written in the past tense: “The Lost Cause supported a belief that the South fought to uphold noble virtues.” This, coupled with an 1869 oil painting entitled “The Last Meeting of Lee and Jackson,” implies that the Lost Cause is a relic of the past, and the museum makes no effort to comment on its persistence to this day. Although the museum offers exhibits tailored to its presence in the city of Richmond, it neglects the significance of Richmond being the ‘city of the Lost Cause.’ Similarly, the single placard detailing the KKK robe on display treats the Klan as a defunct, historical organization and makes no mention of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation and its role in reviving the KKK, beginning in the early 20th century and continuing to this day. I hoped such a contemporary museum would better address the persistence of these supposedly ‘historical ideologies’ into our time.

However, I found the limited space devoted to the Reconstruction era disappointing. A single placard gave a short description of Lost Cause ideology, notably written in the past tense: “The Lost Cause supported a belief that the South fought to uphold noble virtues.” This, coupled with an 1869 oil painting entitled “The Last Meeting of Lee and Jackson,” implies that the Lost Cause is a relic of the past, and the museum makes no effort to comment on its persistence to this day. Although the museum offers exhibits tailored to its presence in the city of Richmond, it neglects the significance of Richmond being the ‘city of the Lost Cause.’ Similarly, the single placard detailing the KKK robe on display treats the Klan as a defunct, historical organization and makes no mention of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation and its role in reviving the KKK, beginning in the early 20th century and continuing to this day. I hoped such a contemporary museum would better address the persistence of these supposedly ‘historical ideologies’ into our time.

Though lots of careful planning went into the design of the American Civil War Museum, the project’s aim of diverse representation– and using the collection of the Lost Cause-linked Museum of the Confederacy to do so–was and continues to be contentious. CEO of the museum and coordinator of the merger Christy Coleman, a black woman, recalls that at one point during the merger “a donor to the Museum of the Confederacy once walked into her office and explained that slavery was the best thing to ever happen to black people.” And though this may seem like an extreme view held only by someone so entrenched in Confederate mythology as to donate large sums to the institution formerly known as the Confederate Museum, one glance at the comments of this Smithsonian article reveal that is not the case:

- “The South did not fight a civil war but was rather engaged in a defensive war of foreign aggression […] This museum is a tragedy of historical revisionism and political correctness that is in keeping with the continuing Federalist propaganda to paint the War between the States as a civil war and to tar the Confederacy, the Confederate veteran, and Dixie with the brush of slavery.”

- “Cultural marxism = historical ignorance run amok. “America Redefined”, indeed. 😔”

- “‘Speaks truths’? You mean another historian and guardian of the past sells out for the politically correct Northern version.”

I find it slightly ironic, then, that the very ideologies that the American Civil War Museum relegates to the status of ‘historical,’ are used at this very moment to discredit the museum’s mission.