I was a nonbeliever. I’ll admit it.

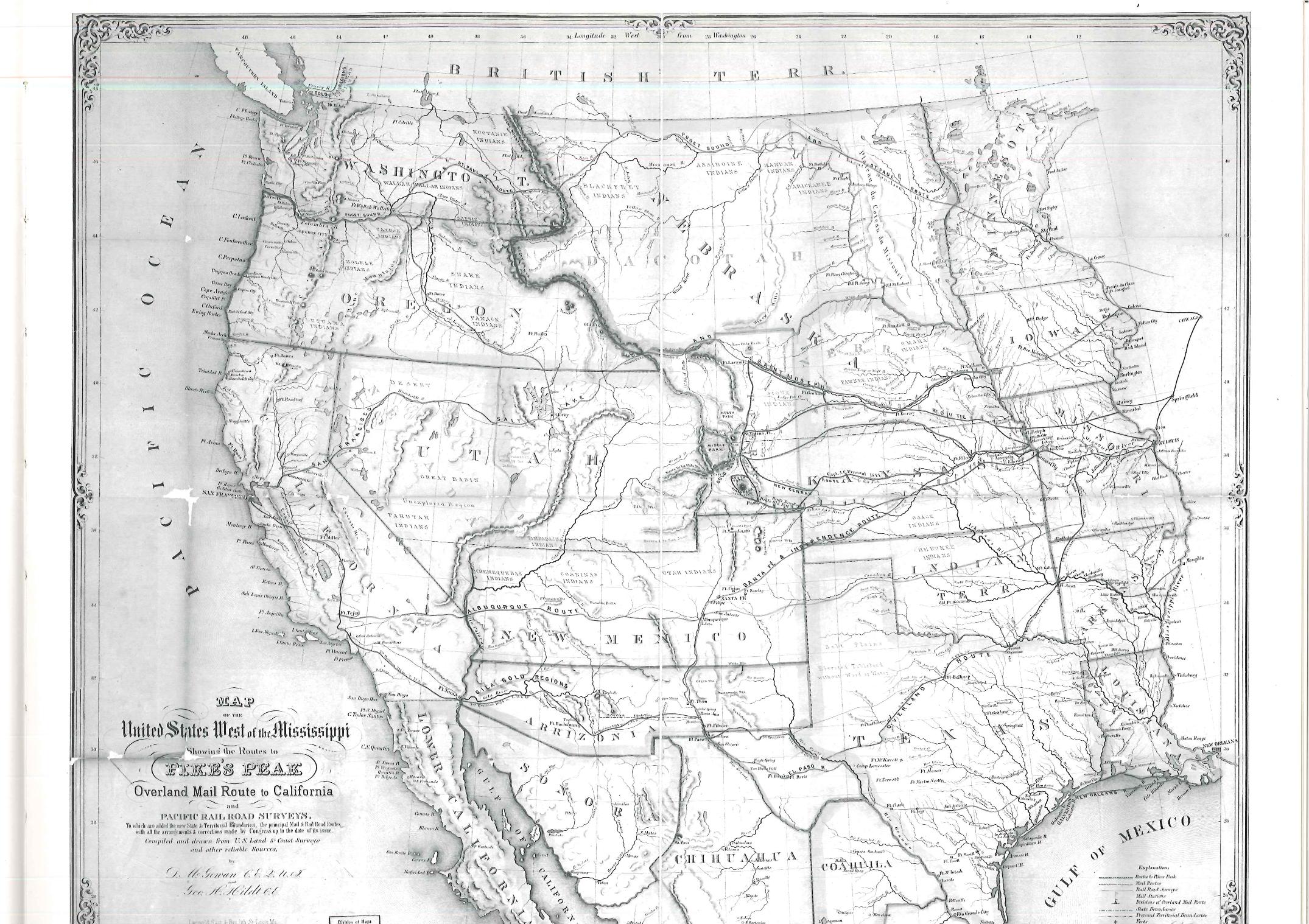

I recall that Dennis Wood mentioned in his book, The Power of Maps that he intended to keep as many maps as he could for 30 days, yet Wood had to give up after 20 days because the number became too overwhelming (34). My thought was: that’s a no brainer. I mean the man has a PhD in Geography – of course he has maps casually lying around. Could the average Joe really be expected to have access to so many? I even challenged the notion of finding a map that’s sole purpose wasn’t to serve as “a way-finding aid” (Schulten). Lo and behold, my theory was disproved at the one place I did not imagine finding a map – but with that being said, maybe I should have known better.

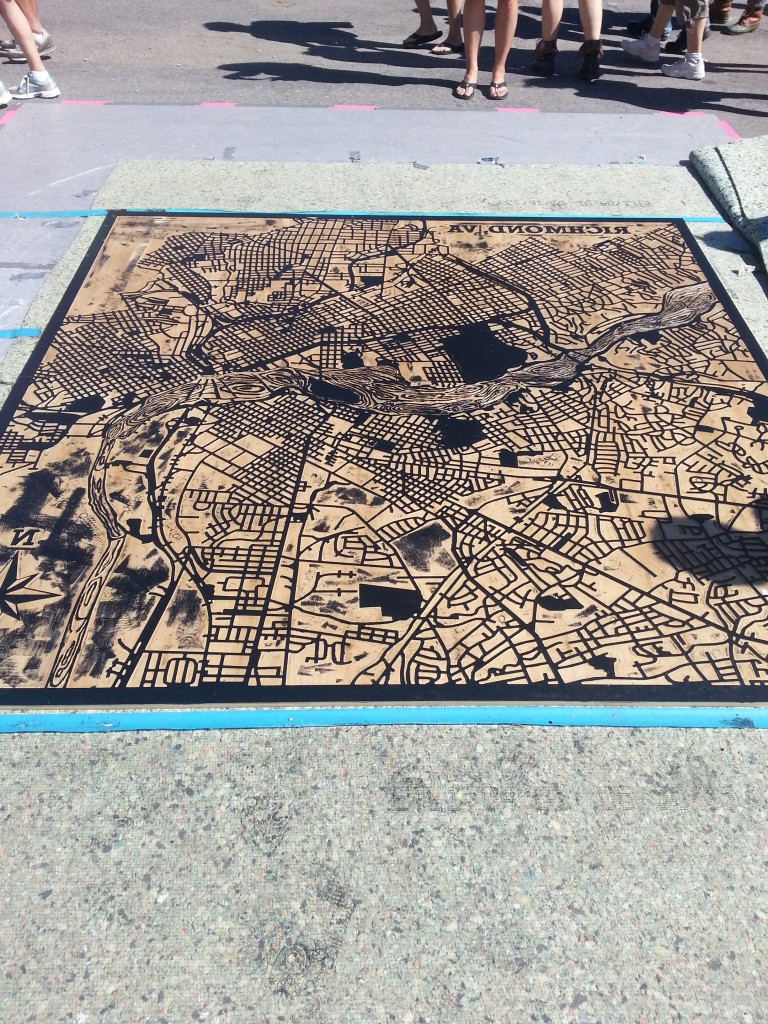

Don’t get me wrong; walking around at the RVA street art festival I enjoyed not being able to take more than a couple of steps without seeing a mind blowing piece that made a statement and considering the large amount of works that was impressive. All of the works of art were artistically unconventional, however, they seemed to belong together. Then I stumbled upon that one piece, which rocked my notion of works belonging to a specialized niche.

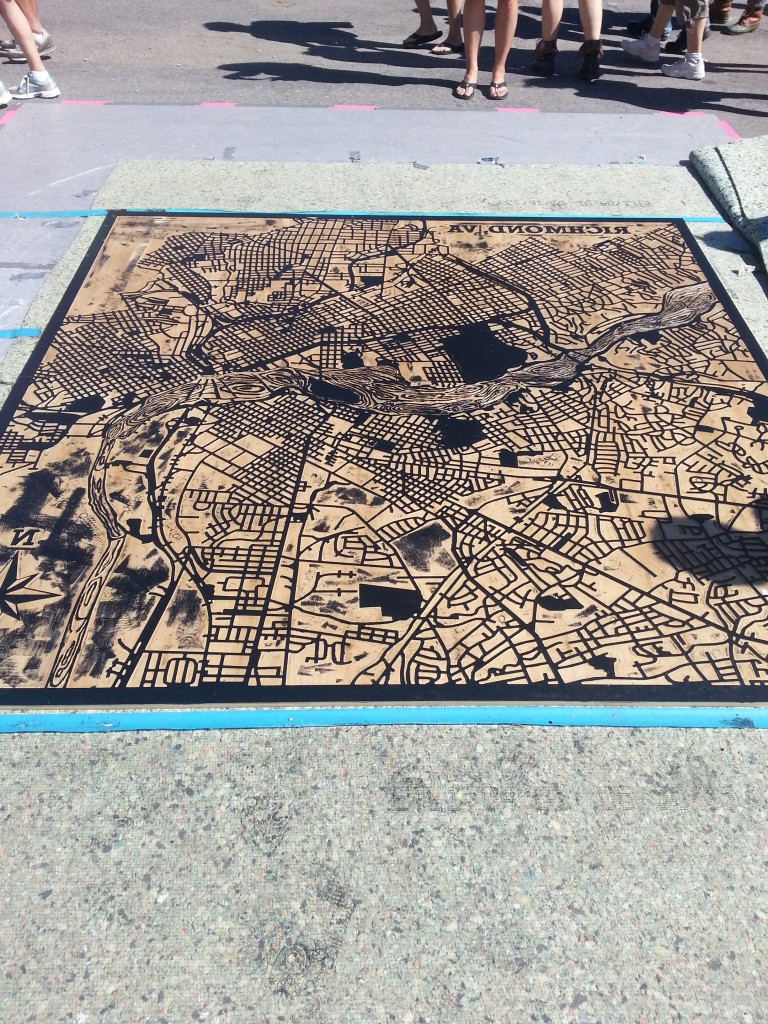

Image 1: Photograph taken at the RVA Street Art Festival on September 14, 2013.

My initial reaction to the map shown above (image 1) was: Really? This break from my class work on maps isn’t working out so well. After I recovered from my minor lapse of despair, I was able to admire the work for what it was. I wasn’t sure what had captured my attention most: the idea that a map could be art or that art could be a map. The awareness between the two is vital because a greater appreciation of cartography is gained from understanding the context of art development. At the same time, it’s refreshing to see innovating techniques of art incorporated into cartography.

Background

The magnified map (approximately 6’ by 6’) of the city of Richmond was done by Studio Two Three, a non-profit print shop. The steam rolling print served to commemorate the city for hosting the RVA street art festival. The attention to detail and preservation of the city in appearance reflects the pride the residents of Richmond have in their city. People from all facets of life took part in the making of the map. A total of 10 interns helped out in the process, most of them are students at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) and some of them are artists actually working in the Richmond area. Pertaining to the technical aspect, I later learned that collaboration occurred amongst GIS Mappers and cartographers to determine the initial map design and geographic boundaries. The actual map image (image 2 seen by clicking on the link below) came about with assistance from graphic designers and then was CNCed at Tektonics Design Group. The hand carving of the wood cuts took approximately 24 hours. And the general public was able to literally carve their names into history by participating in the hand carving of the James River at an event called First Fridays in which the city of Richmond hosts activities for the community. Once that was completed, the work got inked up and was rolled out at the street art festival using steamrollers (Rich). So not only does the map serve as a visual representation of a community linked together through the arteries of the city but it is an example of the city coming together to form a personal community as well.

Steamrolled RVA map

Map as Art

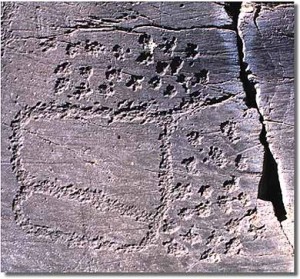

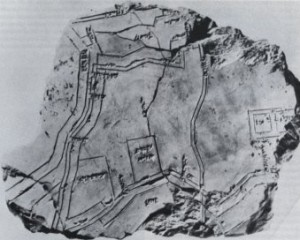

There is a saying about the fluidity of life coming full circle. And this steam rolling print map of Richmond serves as an example. It’s a remake of a very old school technique that scientifically dates back to 25,000 to 4,100 BCE. Since man has been surrounded by nature, he discovered the necessity to distinguish natural elements and used the land before him to serve as a medium. Ever since there have been examples of prehistoric art with cartographic elements such as hills, rivers, and settlements. The earliest signs of humanity’s cartographic observance of the world can be traced down to rock paintings (pictographs) and rock engravings (petroglyphs) just like the ones shown below (“Prehistorical Cartography”).

Image 3 is of a petrogliph from Borno in Valcamonica, Italy. Dated to be from the Bronze age anywhere from 6000 -700 BCE.

Image 4 is of the Hilprecht Collection that is located at the Friederich – Schiller-University, Jena (date unknown).

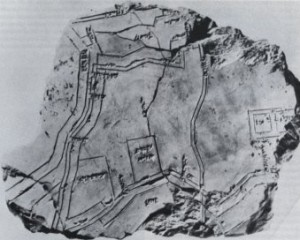

Image 5 is a map of the Wadi al-Hammamat goldmines from around 1500 – 1085 BCE.

I consider the images shown above similar to the style of the Richmond steam rolled map because they all represent a period of time where humanity uses the most sophisticated technology accessible to embody its surroundings. The canvas started out as rock shifted to plaster and wood, and six thousand years later these natural mediums have withstood the test of time. If anything has changed (aside from technology), it is the importance of precision in our everyday world.

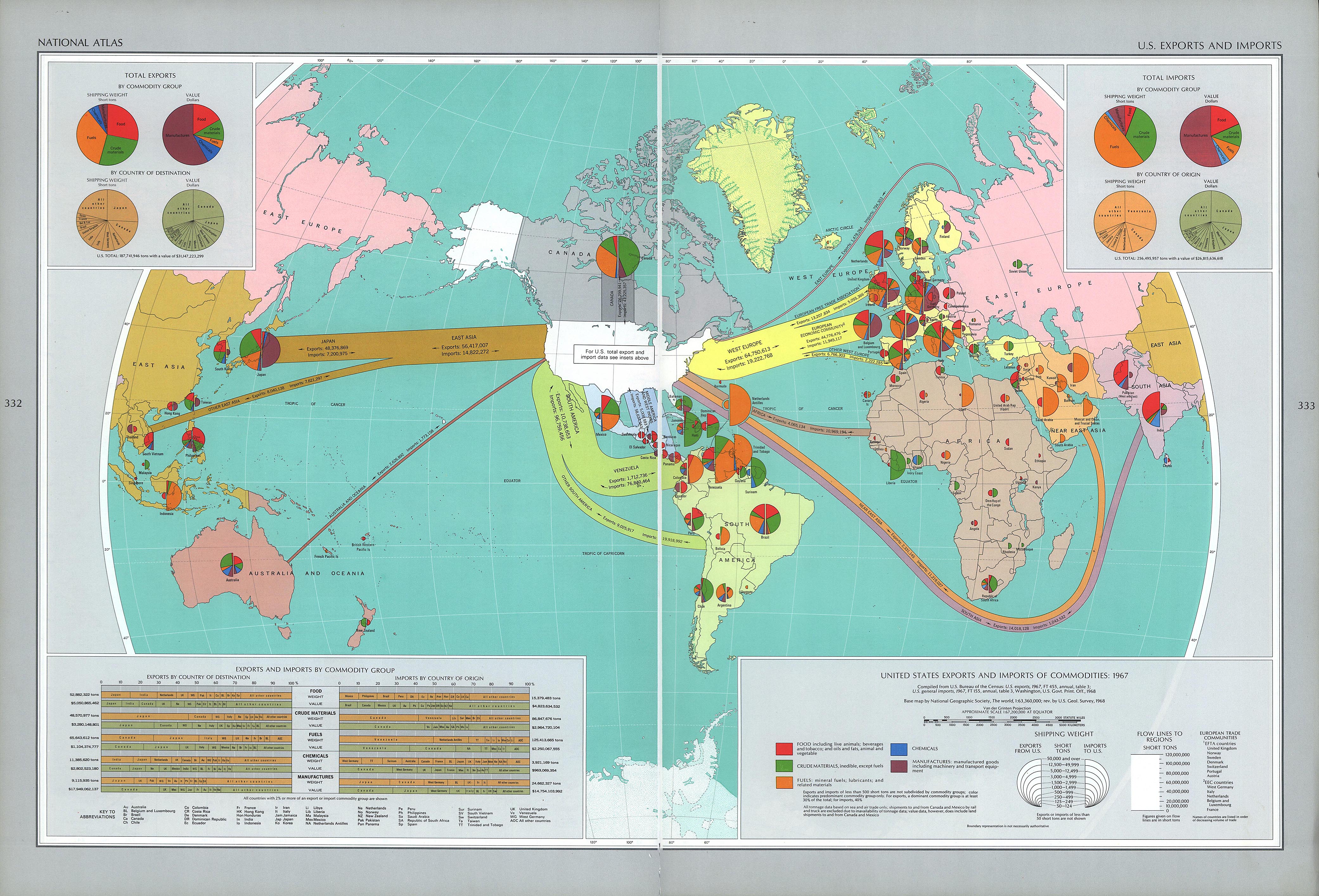

Over time, society has developed the need to rely on details (as can be seen through image 6). The rock paintings descent throughout the years establishes a sense of direction (literally and in convention) and demonstrates an increasing awareness of the environment. An initial impression of the world is based on the primary senses of seeing and touching. Afterwards, there is an organized foundation revolving around spatiality, perception of a reality, and exploration that flourishes. Maintaining a balance between the chaos of orientation and artistic expression requires a scientific edge to tie both elements together. This will factor into the difference between being an expressionist with a drawing of an individual’s take on the world and providing a useable map that respectfully serves as a reflection of a vision. The creator of a map takes his or her abstraction of the world and grounds it with universal symbols, scales, and logic.

Image 6: Both this photograph and steamrolled RVA map were provided by Michelle Rich. This image shows a person working on the wood cut aspect of the map.

Art as Map

My second reaction: does anyone have a mirror? For some reason, I could not wrap my mind around how I was supposed to locate anything on the map. Seeing how I had recently moved to the city of Richmond, and served as witness to numerous maps I should have been able to easily identify places. However, if it weren’t for the label on top of the map, I would be completely lost to the most basic information such as the region the map was showing. Suddenly, the realization of how easily my perception can be altered crept into my mind. Art forces viewers to look at reality through the lens of an alternate universe and so does this map. The viewer is used to reading things from left to right and all of the sudden has to hone in on the littlest details to understand the placement of landmarks. I found it amusing that if I covered the compass of the original map and the label, then I would have not even known the map was reversed. However, the simple understanding of knowing the map was “different” was enough to mess with my mind. I feel that the public can get so caught up with a map varying in projection, text, and other elements that the “bigger picture” is lost to all the noise around it.

Summary

It all started with a smooth wooden surface. A utensil was used to peel away layers and created dimensions that materialized the artists’ vision into a physical reality that could be admired. Even though the art piece is clearly a map, the process in making the map parallels the work put forth into making a map.

- First, this wood cut technique can be traced down through the span of time alongside the development of cartography. This shows that time does not require change, but encourages enhancements to an art form for the better. In the world of cartography, new developments in equipment allow for a hidden chest of knowledge to be exposed.

- Second, the combination of old school methods (as well as medium) and modern day technology reflects how society builds up from past experiences. For example, when creating a map what is the initial step? To consult currently existing maps. Places may have changed and require alterations, on the other hand places may have stayed the same and those features are kept. No matter what technology is at hand, a cartographer will always refer to basic skills and make calls accordingly.

- Lastly, the visual appearance of a map has results that vary. Many factors come into play: there is a scientific and human component that stresses accuracy, the pressure of combining numerous truths to make one reality, and receptiveness of its audience. Despite all these obstacles, a map’s purpose is ultimately to guide the user to some sort of finish line (literally or metaphorically speaking), nevertheless the Richmond map itself is the finish line for the Richmond community. It says this is what we have accomplished together as a united front.

To acknowledge a map as “a way-finding aid” is a nice place to start. However, there is so much more beneath the surface. A map can and should be used for other means such as displaying how far society has come, the capabilities of its people, and conveying a sense of belonging.

Marissa Nino

Works Cited:

Prehistorical Cartography. Tutorials in the History of Cartography. Web. 29 Oct. 2013.

Rich, Michelle. Personal interview. 14 Sept. 2013.

Schulten, Susan. The Graphic Foundations of American History. Mapping the Nation (2012): 1-40. Web. 1 Sept. 2013.

Wood, Dennis. The Power of Maps. New York: The Guilford Press, 1992. Print.