Pulp Fiction abounds with larger-than-life heroes who seemingly achieve more than any mere mortal could hope to accomplish in one lifetime. Mainstream society rejects such notions as mere Romanticism and advises us to set our sights lower — however, such people do exist.

This is the story of one such person.

The woman who would become known as the Bronze Venus was born into a life of poverty in the Negro slums of St. Louis in 1906, the daughter of Vaudeville performers. She did not intend to follow in her parents’ footsteps. However, abandoned by her father and abused as the domestic servant of a wealthy family, she found herself homeless and starving on the city streets; so, when dancing for pennies on the corner led to an invitation to perform in a local chorus line, she was not slow to accept.

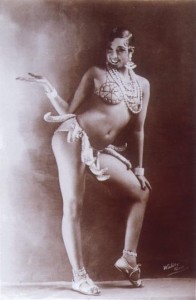

Her natural talents quickly became apparent. Before she was out of her teens, she had moved to New York and had become the highest paid chorus girl in Vaudeville. By her early 20s, she was charming audiences in at the Folies Bergère in Paris with her uninhibited eroticism and comedic antics.

Josephine Baker quickly became one of the most famous women in the world. Her success allowed her to be financially independent, quite rare for a woman of that era and unheard of for a Black woman. As an artist, she was an innovator. In addition to pushing the boundaries of eroticism and nudity, even by the standards of the Roaring 20s, she was the first Black woman to star in a major motion picture and is credited with introducing the Jazz Age to Europe.

After more than a decade of increasing success as an exotic performer (complete with pet cheetah), mitigated only somewhat by experiences with racism in the United States, Baker had become a French citizen and did not hesitate to answer the call when World War II broke out. She was recruited by French Military Intelligence and, later, the French Resistance to obtain and conduct information vital to the war effort.

hesitate to answer the call when World War II broke out. She was recruited by French Military Intelligence and, later, the French Resistance to obtain and conduct information vital to the war effort.

Her celebrity status allowed her to rub shoulders with movers and shakers at embassies throughout Europe and her charm allowed her to gather data about enemy airfields, harbors, and troop movements, which she would then convey written in invisible ink on her sheet music and in notes pinned in her underwear. She was, in short, a spy. In addition, her home in the south of France became an unofficial headquarters for the Free French movement, where operatives could obtain visas.

Throughout the war, Baker also performed freely for the troops and worked as a nurse for the Red Cross. Many Allied soldiers remembered her generosity and healing ministrations throughout the remainder of their lives.

For her efforts, she was awarded the Croix de guerre and the Rosette de la Résistance, and was made a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur by General Charles de Gaulle.

After the war ended, Baker’s celebrity status was heightened by her wartime heroism, and she was not afraid to use her newfound clout. Returning to the United States after many years, she refused to perform for segregated audiences– most venues, most notably in Miami and Las Vegas, gave in to her demands, resulting in a sold-out national tour. She was named the NAACP Woman of the Year in 1951 and May 20th was declared Josephine Baker Day. A parade was held in her honor.

All was not wine and roses, however. She was turned away by dozens of hotels for being Black and received death threats from the Ku Klux Klan. A confrontation at the New York Stork Club (in which she was befriended by Grace Kelly, a hero in her own right), resulted in the revocation of her visa for several years.

Nevertheless, Baker continued to work with the Civil Rights Movement, and was an ally of the NAACP and Martin Luther King. She spoke at the historic March on Washington in 1963 (the only woman to do so) and was heartened by the sight of so many Blacks and Whites standing shoulder to shoulder.  “Salt and pepper,” she said. “Just what it should be.” When Doctor King was killed, she was offered the leadership of the Civil Rights Movement by his widow, but she declined. By then, she had a family to think about.

“Salt and pepper,” she said. “Just what it should be.” When Doctor King was killed, she was offered the leadership of the Civil Rights Movement by his widow, but she declined. By then, she had a family to think about.

Her family at that time consisted of her husband, Jo Bouillon, a French conductor, and a dozen adopted children who she called her Rainbow Tribe (as well as a menagerie of exotic pets). The children were of a variety of backgrounds– European, Asian, Hispanic, Middle Eastern– and were a testament to Baker’s belief that “Surely the day will come when color means nothing more than the skin tone, when religion is seen uniquely as a way to speak one’s soul; when birth places have the weight of a throw of the dice and all men are born free, when understanding breeds love and brotherhood.”

Josephine Baker died in 1975 from a cerebral hemorrhage, following a retrospective performance in Paris that was attended by celebrities, royalty, and dignitaries from all over the world. She received full French military honors and a public funeral attended by tens of thousands.

Today there are parks and streets that bear her name, she is the subject of multiple books, movies and plays, and there are museums and memorials from Missouri to Monte Carlo that pay tribute to this underprivileged Black woman from the streets of St. Louis who championed sexual freedom, provided a role model for independent women, fought the Axis, stared down the Klan, and set an example of human fellowship that is still needed today.

Mere Romanticism indeed. Such people do exist.

– – – – – – – – – – –

Rick Hutchins was born in Boston, MA, and is a regular contributor to this blog. In his quest to live up to the heroic ideal of helping people, he has worked in the health care field for the past twenty-five years, in various capacities. He is also the author of Large In Time, a collection of poetry, The RH Factor, a collection of short stories, and is the creator of Trunkards. Links to galleries of his art, photography and animation can be found on http://www.RJDiogenes.com.

Two of Hutchins’ previous essays on heroes appear in our book Heroic Leadership: An Influence Taxonomy of 100 Exceptional Individuals.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –