This post is based on the following chapter in the Encyclopedia of Heroism Studies:

- Allison, S. T. (2024). Constructions of Heroism. In S. T. Allison, J. K. Beggan, and G. R. Goethals (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Heroism Studies. Springer Nature.

By Scott T. Allison

By Scott T. Allison

Heroism is considered a “construction” because it is a concept and set of behaviors that are shaped and defined by many aspects of people, society, and contexts. The perception of who is considered a hero, what heroic actions entail, and the qualities associated with heroism can vary significantly as a function of different types of constructions. There are at least 12 different ways that heroism has been constructed, as follows:

- Perceptual Construction

Gestalt principles of perceptual organization can contribute to seeing heroes where there may be none through the process of pattern recognition and the way our brains organize and interpret visual information (Goethals & Allison, 2019). Gestalt psychology emphasizes that the human mind tends to perceive objects and scenes as whole, organized entities rather than a collection of individual parts. This can lead to the perception of meaningful patterns even in ambiguous or random stimuli. Selective attention can lead to a biased perception, making certain individuals appear heroic even when their actions might not objectively warrant that label.

In addition, the Gestalt principle of closure refers to our tendency to mentally complete incomplete or fragmented information to perceive meaningful wholes. In the case of perceiving heroes, our minds may fill in gaps in information or actions, constructing a narrative that portrays certain individuals as heroic even if the complete story might not support that conclusion. The principle of proximity, moreover, suggests that objects that are close together in space tend to be perceived as belonging to the same group. In the context of seeing heroes, our minds may group together certain actions or individuals based on their proximity, even if the connections between them are tenuous or coincidental. This grouping can create the perception of heroism in individuals who may not have acted heroically at all.

- Mental Construction

Our minds and preconceived notions significantly impact our perception and interpretation of events, leading to constructions of heroism (Goethals & Allison, 2012). People tend to construct narratives about themselves and others based on schemas, scripts, stereotypes, biases, attribution theory, and other cognitive mechanisms grounded in psychology and neuroscience. Fiske and Taylor (2013) describe many cognitive biases than can lead to skewed constructions of heroism. For instance, the confirmation bias causes individuals to seek out evidence supporting preexisting assumptions while disregarding contradictory data. Similarly, fundamental attribution error attributes behavior solely to internal dispositions instead of external circumstances. Additionally, recency effect increases the likelihood of recalling more recent instances over older ones even if less significant. Lastly, availability heuristic magnifies importance of easily recalled instances over obscured incidents.

These cognitive processes shape how individuals assess heroism in ambiguous scenarios. If someone expects another person to display heroic behaviors because of gender, race, ethnicity, education, career choice, or another trait, then they might mistake everyday acts as extraordinary feats deserving recognition. Conversely, dismissing potential heroes due to negative characteristics or past mistakes prevents appreciating actual courage during crises. Therefore, understanding our innate tendencies helps avoid premature conclusions about hero status and encourages open-minded appraisals without jumping to hasty judgments based upon limited information or presupposed qualities.

- Motivational Construction

Motivational biases can strongly influence people’s perceptions of heroism. Becker’s (1973) concept of the universal urge to heroism refers to a fundamental desire within all human beings to strive for greatness and transcendence. According to Becker, people are driven by a deep longing to leave a lasting impact, to be significant, and to overcome their own mortality. The universal urge to heroism manifests itself in various forms, such as artistic creation, scientific discovery, spiritual enlightenment, political leadership, or acts of altruism and selfless sacrifice for others.

Goethals and Allison (2019) coined the phrase, the romance of heroism, referring to people’s idealistic and quixotic notions of heroes and heroic leadership. This romantic longing for heroes fuels romanticized ideas about who heroes are, what they are like, and when they should emerge. The romance of heroism leads to exaggerated perceptions of the heroic qualities in certain types of people, especially under conditions of stress and uncertainty. This explains why observers frequently imbue heroic attributes onto public figures possessing qualities matching their private aspirations for esteem, love, belonging, respect, admiration, validation, success, wealth, celebrity, and significance. As a result, individuals often idealize or idolize role models who personify their yearnings for significance in society.

- Metaphorical Construction

Joseph Campbell (2012, 45) once said, “Every myth, that is to say, whether or not by intention, is psychologically symbolic. Its narratives and images are to be read, therefore, not literally, but as metaphors.” People use metaphors to evoke powerful and vivid images that capture the essence of heroism. Here are some common metaphors used to describe heroes include a shining star, a beacon of hope, a pillar of strength, a guardian angel, a knight in shining armor, a rock, an anchor, a warrior, a lighthouse, a golden heart, a phoenix rising from the ashes, a champion, a rainbow after a storm, a god, and a legend. These metaphors help to paint vivid and evocative images of heroes, capturing the essence of their heroic qualities, actions, and impact on others.

Allison, Goethals and Kramer (2017) reviewed the metaphors that scholars have used to describe heroism. The use of metaphor throughout the history of science has helped scholars identify fresh frameworks for identifying new phenomena worthy of scrutiny. Thomas Carlyle’s (1841) great man theory of heroic leadership offered the first metaphor of human agency as paramount in understanding heroic action. Kinsella, Ritchie, and Igou’s (2015) prototype analysis of a hero’s characteristics serves as an example of research that follows in this metaphorical tradition. Campbell’s (1949) monomyth of the hero’s journey represents another metaphor of heroism. The idea that heroism is a journey of growth would seem to underlie research on heroism as a lifelong developmental process (Allison et al. 2019).

Franco and Zimbardo have composed two metaphors of heroism. The banality of heroism metaphor (Franco & Zimbardo, 2006) emphasizes the human universality of heroism and fosters the heroic potential in everyone. The metaphor of heroic imagination (Franco et al., 2011) “can be seen as mind-set, a collection of attitudes about helping others in need, beginning with caring for others in compassionate ways, but also moving toward a willingness to sacrifice or take risks on behalf of others or in defense of a moral cause” (p. 111).

- Spiritual Construction

The world’s spiritual traditions often represent heroism through various archetypes, teachings, and stories that inspire individuals to overcome challenges, cultivate virtues, and strive for personal and collective transformation. Many spiritual traditions highlight the heroism of selfless sacrifice and compassion for others. Heroes are often portrayed as individuals who put the needs and well-being of others above their own, showing great empathy and kindness. Spiritual heroes frequently face trials, temptations, or difficult circumstances, which they must overcome to achieve their goals. These struggles represent the internal and external battles that individuals face on their spiritual journeys. Heroic figures in spiritual tales often confront malevolent forces or negative aspects of the human condition, symbolizing the struggle against ignorance, ego, greed, and hatred. They embody the triumph of good over evil.

Spiritual heroes embody and exemplify virtues such as courage, wisdom, humility, patience, and love. These qualities serve as guiding principles for others on their own heroic paths. Spiritual heroes are often depicted as individuals who have a profound connection with the divine or the sacred. Their actions and accomplishments are seen as a manifestation of divine grace and guidance. Spiritual heroes serve as role models, motivating individuals to make positive changes in their lives and communities. They encourage people to become agents of transformation and contribute to the betterment of the world.

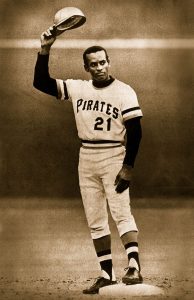

- Image Construction

Human societies have used a wide range of images to represent heroism, drawing inspiration from mythology, folklore, literature, art, and popular culture. These images often reflect the values, beliefs, and aspirations of different cultures and historical periods. Heroic images are influenced by cultural, social, and technological changes, and they play a crucial role in shaping the collective imagination and inspiring individuals to strive for greatness, make positive contributions, and face challenges with courage and resilience.

Some common images of heroism found across various societies include everyday heroes such as teachers who inspire their students, caregivers who selflessly care for others, or community leaders who work for the common good; inspirational figures such as Nelson Mandela, Joan of Arc, and Mother Teresa; superheroes such as Spider-Man and Wonder Woman; social activist heroes such as Susan B. Anthony, Mahatma Gandhi, and Che Guevara; and first responders such as firefighters, nurses, law enforcement, military, and paramedics. In Christianity, the image of the cross is a powerful symbol of sacrifice, suffering, and redemption; in Buddhism, the image of the Buddha symbolizes enlightenment and awakening; in Hinduism, the image of Lord Shiva with his third eye represents spiritual wisdom.

- Ecological Construction

Ecological constructions of heroism refer to the human-environment interaction and how it plays a role in becoming heroic and in identifying heroic elements in others. This type of construction was proposed by Efthimiou (2017), who noted that “the body does not, and cannot, therefore, exist independent of its environment” (Johnson 2008, 164). In the context of prosocial behavior, Lerner and Schmid Callina (2014) proposed a relational developmental systems model of character development that adopts this ecological approach. The model describes how our senses, bodily sensations, awareness, perceptions, neurochemistry, cellular behavior, physical expressions, language and so forth are inextricably connected with our interactions and perceptions of the world.

Efthimiou (2017, 146) argues that “the heroic body as biological organism is housed in the pre-conscious, the habitual body and the body schema.” Heroism and heroic descriptions of others are constructions based on the interaction between our sensory-motor experiences and aspects of our physical world such as shapes, color, temperature, and surface textures. Moreover, different types of intelligence embedded in our bodies, such as emotional intelligence and physical intelligence, are integral part of the heroic body. These embodied intelligences and their interactions with the physical world shape how heroic action is performed and perceived.

- Social Construction

Heroism is socially constructed through the collective beliefs, values, and norms of a particular society (Rankin and Eagly 2008). The social construction of heroism can vary significantly across different societies and can be affected by a society’s values, history, mythology, political system, media, religion, philosophy, gender norms, national identity, collective memory, and social movements. Decter-Frain, Vanstone, and Frimer (2017) offered a social constructivist approach to how groups identify moral heroes. These scholars argue that “groups may catapult relatively ordinary individuals into moral heroism” (121). Groups do so by giving these ordinary people titles and awards, propagating heroic portraits, and encouraging them to give inspiring speeches. Social constructions of moral heroes benefits a society by promoting ingroup identity, providing a rallying point around which to unite, encouraging cooperation, and providing moral models (Kinsella, Ritchie, and Igou 2015).

The social construction of heroism is dynamic and can evolve over time. As societies change, so do their definitions and representations of heroism. What is considered heroic in one era or culture may not necessarily hold the same status in another. Understanding the social construction of heroism helps us analyze how societies collectively assign value and meaning to certain actions, individuals, and ideals, contributing to the shaping of cultural identity and aspirations. Understanding how societies construct their heroes is important for understanding how heroes embody societal norms, and how heroes reflect the values, beliefs, and aspirations of a society. The social construction of heroes enables individuals to navigate the complexities of culture, power dynamics, and collective values.

- Historical Construction

Throughout history, heroes have been constructed and celebrated by societies in various ways. From antiquity to modern times, cultures have created heroic figures and narratives that embody their values, ideals, and aspirations. Examples of historical constructions abound. Ancient Greek’s constructed the mythological figure of Achilles, the hero of the Trojan War and a central figure in the Iliad. In Norse mythology, Thor, the god of thunder, and Odin, the All-Father, were revered as heroic figures. The epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest known literary works, tells the story of a legendary Sumerian king. In ancient China, Guan Yu was a general known for his loyalty, martial prowess, and unwavering adherence to Confucian virtues. Ancient India constructed the heroism of Arjuna, a skilled warrior and one of the Pandava brothers. His moral dilemma and inner conflict on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, as depicted in the Bhagavad Gita, exemplify the complexities of duty, righteousness, and heroism in the face of adversity.

Medieval Europe revered the legendary King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table. In Medieval Japan, Minamoto no Yoshitsune was a brave samurai warrior during the late Heian and early Kamakura periods in Japan. During the Renaissance, Joan of Arc was constructed heroically for her unwavering faith, courage, and sense of divine mission. Early in its history, the United States constructed George Washington as an iconic hero during the American Revolution. These examples illustrate how societies have drawn from historical events to construct heroes from a diverse range of contexts, including mythology and literature. Each hero embodies the specific values and cultural ideals of their time and place, reflecting the dynamic nature of heroism and its connection to the collective identity of societies throughout history.

- Media Construction

In modern society, the media has played a significant role in constructing and shaping heroes. Media representations of heroes are guided by the latest technology delivery systems and reflect contemporary values, cultural trends, and societal aspirations. The rise of social media gave rise to social media influencers and internet personalities who are celebrated as heroes or anti-heroes. The media provides extensive coverage of certain individuals, focusing on their achievements, talents, philanthropy, or charismatic personalities. Through repeated exposure in news articles, interviews, and entertainment shows, these figures become familiar and influential in the public eye. A celebrity thus becomes, in the words of Boorstin (1961, 8), “a person well known for his well-knownness.”

Social media platforms such as Instagram have a profound influence on creating heroes by providing a powerful and accessible platform for individuals to cultivate and promote their public image. The nature of Instagram, with its emphasis on visual content and personal branding, allows users to present themselves in curated and aspirational ways, leading to the construction of heroic personas. This hero construction derives from personal branding, the showcasing of talents and achievements, philanthropy and social impact, engagement with fans, the fostering of fan communities, visual storytelling, and collaborations and partnerships.

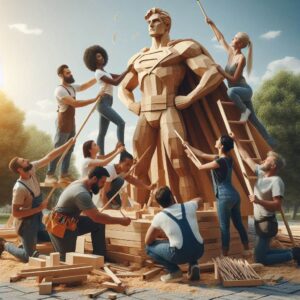

- Physical Construction

Societies create physical representations of heroes as a way to honor, commemorate, and celebrate individuals or figures who are seen as embodying heroic qualities or making significant contributions to their communities or the world. These representations take various forms, including statues and sculptures often on display in public spaces, parks, and squares; war memorials erected to honor fallen soldiers and veterans; portrait paintings and portraits;

architectural monuments; named streets, parks, and buildings; national symbols and currency; hall of fames and walk of fames; public commemorations and ceremonies; religious and spiritual places; and digital memorials. These physical representations serve not only to celebrate the heroic deeds and qualities of specific individuals but also to reinforce collective memory and cultural identity. They play a crucial role in preserving historical narratives and inspiring future generations to aspire to greatness and contribute positively to society.

- Cultural Construction

Different cultures hold different conceptions of heroism (Sun, Kinsella, and Igou 2023). To illustrate cultural differences in hero construction, we will compare hero construction in Ancient Egypt with hero construction in modern America. The ancient Egyptians highly valued and actively cultivated the worship and glorification of certain individuals who were seen as heroic or semi-divine figures. These culturally constructed heroes were dominated by images of

Modern US culture offers an interesting contrast with that of ancient Egypt. American culture fosters the creation of cultural heroes through the media and entertainment industry. Actors, musicians, athletes, and other public figures are elevated to hero status through extensive media coverage, celebrity endorsements, and fan engagement. Movies, TV shows, music, and sports events often glorify these figures, emphasizing their talent, achievements, and charisma.

Reality TV shows and social media platforms have given rise to a new breed of cultural heroes. Individuals who gain popularity through reality TV competitions or social media influence can become widely recognized figures with large followings. American culture celebrates entrepreneurs, inventors, and innovators who have made significant contributions to society. American culture places a strong emphasis on sports heroes. Athletes who achieve exceptional success, break records, or display extraordinary dedication become cultural icons.

Conclusion

Heroism appears to be a construction reflecting many factors ranging from the micro (biological factors) to the macro (societal factors). This undeniable fact does not preclude the need to objectively identify, categorize, and encourage real heroic action. Hero training programs based on current constructions of heroism are undeniably important in promoting social harmony and progress. This chapter merely underscores the reality of heroism being subject to change based on changes in history, religion, politics, psychology, media, and many other forces that are constantly in flux.

References

Allison, S. T., Goethals, G. R., Marrinan, A. R., Parker, O. M., Spyrou, S. P., Stein, M. (2019). The metamorphosis of the hero: Principles, processes, and purpose. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 606.

Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. New York: Free press.

Boorstin, D. J. (1961). The image. New York: Atheneum.

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. New York: New World Library.

Campbell, J. (2012). The Inner Reaches of Outer Space. New York: New World Library.

Decter-Frain, A., Vanstone, R., & Frimer, J. A. (2017). Why and how groups create moral heroes. In S. T. Allison, G. R. Goethals, & R. M. Kramer (Eds.), Handbook of heroism and heroic leadership. New York: Routledge.

Efthimiou, O. (2017). The hero organism: Advancing the embodiment of heroism thesis in the 21st century. In S. T. Allison, G. R. Goethals, & R. M. Kramer (Eds.), Handbook of heroism and heroic leadership. New York: Routledge.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (2017). Social cognition: From brains to culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Franco, Z. E., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2006). The banality of heroism. Greater Good, 3, 30-35.

Franco, Z. E., Blau, K., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2011). Heroism: A conceptual analysis and differentiation between heroic action and altruism. Review of General Psychology, 15, 99-113.

Goethals, G. R. & Allison, S. T. (2012). Making heroes: The construction of courage, competence and virtue. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 183-235.

Goethals, G. R., & Allison, S. T. (2019). The romance of heroism and heroic leadership: Ambiguity, attribution, and apotheosis. West Yorkshire: Emerald.

Kinsella E. L., Ritchie T. D., Igou E. R. (2015a). Zeroing in on heroes: A prototype analysis of hero features. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(1), 114–127.

Rankin, L. E., & Eagly, A. H. (2008). Is his heroism hailed and hers hidden? Women, men, and the social construction of heroism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(4), 414–422.

Sun, Y., Kinsella, E. L., & Igou, E. R. (2023). On cultural differences of heroes: Evidence from individualistic and collectivistic cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

Like this:

Like Loading...